From the Editor

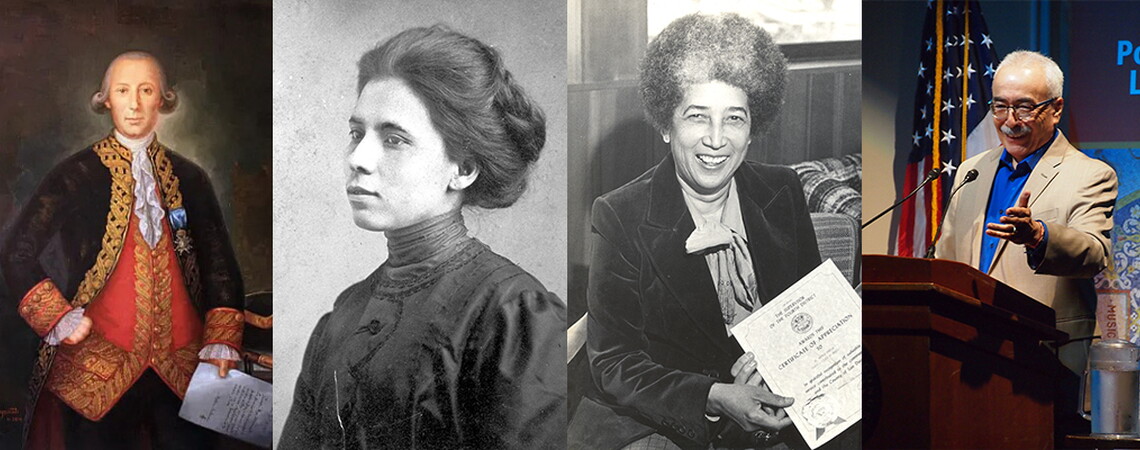

In this issue of History Now, we continue our mission of ensuring that the stories of Americans of all races and ethnicities appear in our national history. “Hispanic Heroes in American History” introduces readers to the accomplishments of distinguished leaders within the diverse Hispanic community of the United States, from the founding era to the present. Their life stories are varied; their fields of endeavor are manifold; but a deep commitment to liberty, democracy, and justice and a sustaining pride in their heritage define them all.

While most Americans know that France helped the colonists mightily in the American Revolution, few realize the critical role Spain played in our victory. In Larrie D. Ferreiro’s essay, “El enemigo de mi enemigo es mi amigo: Bernardo de Gálvez and the Battle That Saved the United States at Its Birth,” the story of Spain’s pivotal role is made clear. Both Spain and France had good reason to delight in the revolt in Britain’s American colonies, for they had lost North American territory to the British in the French and Indian War. Operating on the principle that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” Spain began to assist the American colonists in their struggle with Great Britain. Even before the Declaration of Independence, Spanish merchants answered the call for aid by providing muskets, gunpowder, and other supplies to the rebels. By 1777, the new governor and military commander of Louisiana, Bernardo de Gálvez, decided to increase this aid to the colonists. By September of that year, Spain and France together had supplied enough weaponry to Washington’s Continental Army to defeat the British at Saratoga. By February 1778, France had signed a treaty with the US; Spain, however, held back. As a colonial power, it hesitated to openly endorse a colonial rebellion, even one against a sworn enemy. Gálvez, however, saw that the British/American conflict opened up the possibility of a reconquest of the Florida territory Britain had acquired in the previous war. His army took Baton Rouge, Mobile, and Pensacola. By 1781, the British had surrendered all of West Florida to Gálvez. This victory played a key role in the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown, for the Spanish, satisfied with their revenge against their enemy Britain, now promised the French king that its fleet would protect his Caribbean territories. This freed up General Rochambeau’s entire fleet to trap Cornwallis. Although his exploits were, of course, for the glory of his own country, it is clear that they proved invaluable to our country’s independence.

In her essay, “Arturo Alfonso Schomburg: Archivist, Institution Builder, and Advocate of Global Black History,” Vanessa K. Valdés traces the life of one of the world’s most important champions of Black culture. Born in 1874 to a free Black woman and a German father in a small Puerto Rican town founded by self-emancipated Black communities, the young Schomburg was told by a teacher that Black people had no history. He spent his adult life proving that this was wrong. At the age of seventeen, he moved to New York City, where he joined a movement of Afro-Cubans and Afro-Puerto Ricans calling for the independence from Spain. In 1904 he published his first article, which marked the centennial of an independent Haiti. Over the decades that followed, he continued to write about global Black history for important African American periodicals. Schomburg believed that history was essential in combatting what Valdés describes as “White supremacist erasure” of Black achievements. In 1926, Schomburg sold his vast private collection of documents, books, and other artifacts to the Carnegie Corporation with the stipulation that they be housed at the 135th Street Branch of the NY Public Library. The Schomburg Collection, as it came to be known, provided “vindicating evidences” of Black contributions to world culture. Schomburg joined the staff of Fisk University and developed the school’s library. From 1932 until the end of his life in 1938, he served as the curator of the 135th Street Library collection. In 1972, the library was renamed the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Countless historians and students of history have made their pilgrimage to the Center in their pursuit of the history of Black citizens of this country and many other nations.

In her essay, “Voices of Democracy: Jovita Idár, the Idár family, and the Struggle against Juan Crow,” Gabriela Gonzalez introduces readers to a family of dedicated and effective reformers who campaigned tirelessly for the rights of Mexicans and Mexican Americans. The Idárs were journalists whose commitment to change spanned two generations. Jovita Idár trained as a teacher but decided she could do more for the cause of equality by joining her brothers in the family’s muckraking newspaper, La Crónica. As discrimination deepened in Texas in the decade between 1910 and 1920, the Idárs worked to combat the racism their people encountered by organizing the El Primer Congreso Mexicanista, a gathering that welcomed Mexican Americans, Mexican immigrants, and Mexican nationals to join the battle against lynching, economic exploitation, and other abuses. Soon after this congress met, Idár helped organize the League of Mexican Women, which focused on benevolent projects and providing free education for poor children in Laredo. She went on to serve as a nurse during the Mexican Revolution, supporting the rebel forces during that struggle. She was fearless. When Texas Rangers came to destroy the printing presses of a radical newspaper, Idár blocked their way. She later served as a precinct judge in San Antonio’s Democratic Party and as co-editor of a Christian newspaper. In recent years she has been recognized, in documentary films and in the press, for her lifetime of activism. In 2021, Laredo renamed a park in her honor. In August 2023, the US mint will release the Jovita Idár quarter as part of the American Women Quarters Program.

In her essay, “Antonia Pantoja, a Nuyorican Builder of Institutions,” Lourdes Torres introduces us to a notable community organizer. Born in poverty in a small barrio outside of San Juan, Pantoja experienced firsthand the vulnerability of the working class and the discrimination against Black Puerto Ricans. Yet rather than succumb to these circumstances, she took action. With a degree from a two-year college and few financial resources, at nineteen, she moved to New York City in 1944. Here she found a circle of young intellectuals who discussed art, philosophy, and politics. Before long, she began what would be a lifelong career of creating leaders who could shoulder the task of improving the lives of Puerto Ricans. She was the consummate organization builder, founding ASPIRA in 1961. ASPIRA worked to help Puerto Rican students develop leadership skills. Today ASPIRA is a national association with chapters in six states. It has advanced civil rights and political equality, and members have become social workers, lawyers, and leaders of grassroots organizations. By 1978 Pantoja had earned a PhD in education and soon after took a position in the School of Social Work at San Diego State University. Here she met her life partner, with whom she established the Graduate School for Community Development in San Diego. In 1983, Pantoja moved with her partner to a small town in Puerto Rico, where she continued her organization-building, establishing PRODUCIR, a community development project. In 1996, she was honored by President Clinton with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In 1998 the couple moved back to New York City, where Pantoja died in 2002. Her talent for motivating people remained remarkable until her death. She believed that the future could be made by cooperation and persistence, once saying, “You make the future, I make the future, we make the future together.”

Francisco A. Lomelí introduces us to a multi-talented poet of Mexican background in his essay, “Juan Felipe Herrera: Poet Laureate and Pioneer of Chicano Literature.” Born to migrant parents in California in 1948, Herrera rose from poverty to become the most accomplished and acclaimed contemporary Chicano writer in the United States, publishing more than thirty books during his career. Herrera learned the value of storytelling from his mother, Lomelí tells us, and acquired a strong work ethic from his father. His poetry is inspired by real people’s lives, concerns, and needs. A lifelong Californian, Herrera earned his BA from UCLA and a master’s degree from Stanford University. His fame rests, however, on his literary experimentalism, which draws on a dazzling variety of writers and thinkers, from García Lorca and Neruda to Malcolm X and César Chávez. Herrera served as California’s Poet Laureate from 2012 to 2014 and as US Poet Laureate from 2015 to 2017. His works, Lomelí notes, are considered landmarks in Chicano literature. Herrera is a writer-activist of passion and commitment, as well as a brilliant innovator who fuses traditional genres with mixed media.

The essays in this issue are supplemented by a wide variety of educational materials from the archives of the Gilder Lehrman Institute, including previously published History Now essays on related topics, spotlighted primary sources from Gilder Lehrman Collection, and videos. The issue’s special feature is a presentation by Carrie Gibson on her book El Norte: The Epic and Forgotten Story of Hispanic North America, an installment of the Institute’s Book Breaks series on October 30, 2022.

We hope, as always, that History Now will be a valuable resource for you in your teaching and research.

Carol Berkin, Editor, History Now

Presidential Professor of History, Emerita, Baruch College & the Graduate Center, CUNY

Nicole Seary, Associate Editor, History Now, and Senior Editor, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

Melissa Reyes, Contributing Editor, History Now 66

Dartmouth College, Class of 2025

Related Resources

Special Feature

“El Norte: The Epic and Forgotten Story of Hispanic North America” with Carrie Gibson (Book Breaks, October 30, 2022)

Issues of History Now

“The Hispanic Legacy in American History” (History Now 53, Winter 2019)

“The History of US Immigration Laws” (History Now 52, Fall 2018)

From the Archives

Essays

“Venezuela’s First Declaration of Independence and US Republicanism: Convergences and Divergences” by Vitor Izecksohn (History Now 61, “The Declaration of Independence and the Origins of Self-Determination in the Modern World,” Fall 2021)

“The US and Spanish American Revolutions” by Jay Sexton (History Now 34, “The Revolutionary Age,” Winter 2012)

“Bridging the Caribbean: Puerto Rican Roots in Nineteenth-Century America” by Virginia Sanchez Korrol (History Now 3, “Immigration,” Spring 2005)

“Historical Context: Mexican Americans and the Great Depression” by Steven Mintz

From the Teacher’s Desk

“Historical Context: Mexican Americans and the Great Depression” by Steven Mintz

“Late 19th- and Early 20th-Century Art and Immigration: History through Art and Documents” by Tim Bailey, 2009 National History Teacher of the Year

Videos

“An African American and Latinx History of the United States” with Paul Ortiz, Book Breaks, May 1, 2022

“Cuba: An American History” with Ada Ferrer, Book Breaks, September 12, 2021

“The Storyteller’s Candle / La velita de los cuentos” by Lucía González (Author) and Lulu Delacre (Illustrator), read by Rich Negron (North American Tour, Hamilton), Hamilton Cast Read Alongs, September 2021

Spotlights on Primary Sources

De Soto’s discovery of the Mississippi, 1541

A report from Spanish Caifornia, 1776