Juan Felipe Herrera: Poet Laureate and Pioneer of Chicano Literature

by Francisco A. Lomelí

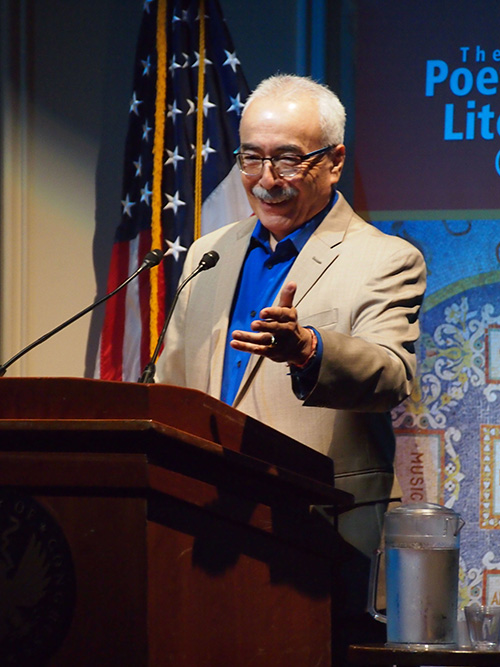

Juan Felipe Herrera, born to migrant parents Felipe Emilio Herrera and Lucha Andrea Quintana in Fowler, California, on December 27, 1948, is a writer unique for his unrelenting spirit of innovation. He boldly expands the boundaries of poetry in the broadest sense of the word and stands out as perhaps the most accomplished and acclaimed contemporary Chicano/Latino writer in the United States. From 2012 to 2014, he served as Poet Laureate of California, cementing his reputation. He was then immortalized when he was selected not once but twice as United States Poet Laureate in 2015–2016 and 2016–2017.

Juan Felipe Herrera, born to migrant parents Felipe Emilio Herrera and Lucha Andrea Quintana in Fowler, California, on December 27, 1948, is a writer unique for his unrelenting spirit of innovation. He boldly expands the boundaries of poetry in the broadest sense of the word and stands out as perhaps the most accomplished and acclaimed contemporary Chicano/Latino writer in the United States. From 2012 to 2014, he served as Poet Laureate of California, cementing his reputation. He was then immortalized when he was selected not once but twice as United States Poet Laureate in 2015–2016 and 2016–2017.

Herrera has been active as a writer for more than half a century. In the 1960s and ’70s, he became involved in the literary renaissance within the Chicano Movement, a Mexican American political struggle for civil rights as well as a cultural celebration of history and heritage. He remained engaged in the post-Movement era of the l990s, and he continues to contribute today. His works are widely considered landmarks in Chicano literature for their groundbreaking content, thematic diversity, and sophisticated experimentalism in terms of style, subject, and perspective. Grounded in an avant-garde poetics, Herrera has produced thirty-four books in an impressive array of genres and subgenres: memoirs, travelogues, mock epics, manifestos of resistance, theatrical pieces, neo-indigenist incantations, treatises on immigration and migration, ethnobiographies, children’s stories, young adult novels, and many other types of writings.

Although his personal journey has taken him far, Herrera had humble beginnings, traveling with his family from farm to farm while harvesting seasonal fruits and vegetables. Herrera’s mother taught him in his childhood the value of the oral tradition of storytelling and songs, and his father instilled in him a strong work ethic and a perceptiveness, particularly of place. These early lessons served him well during his long career, and his origins remain the bedrock of his writing. He has often been described as a “people’s poet,” with a firm understanding of others’ lives, concerns, needs, social circumstances, and aspirations. He is a master of tapping into the collective psyche, unveiling human anxieties and desires while providing an insider’s view of what makes people tick. Keen insight and verbal precision mark his work and have made his reputation as a vanguard writer.

Herrera has received considerable praise and multiple national awards and honors beyond his poet laureateship. He is an elected member of the prestigious Board of Chancellors of the Academy of American Poets and the recipient of two Latino Hall of Fame Poetry Awards, the Ezra Jack Keats Award (1997), the PEN/Beyond Margins Award (2009), the National Book Critics Circle Award in Poetry (2009), and the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize (2022), among other honors. In 2023, he received the distinguished Robert Frost Medal from the Poetry Society of America.

From the 1950s to the early 1970s, Herrera’s personal journey took him to the San Diego, California area, where he developed his literary sensibilities and immersed himself in the barrio experience. From the mid-1970s to the 1980s, he lived in the Mission District of San Francisco, where he became a part of the pan-Latino cultural ecosystem. He completed his BA at UCLA in 1971 with a major in social anthropology. Fascinated with Indigenous peoples, he obtained his MA at Stanford University in 1980 and began to study for a PhD, which he did not complete. Herrera’s intense interests in music, art, photography, and theater led him to experiment with various art forms and styles. In 1971 he founded the theater troupe Teatro Toltec and, in 1979, Teatro Zapata.

Herrera’s proclivity for innovation has allowed him to explore diverse aspects of the Chicano experience. His versatility, resourcefulness, and cleverness enable him to experiment with multiple literary formats and modalities, oftentimes in deft Spanglish. The vastness of his learning and many cultural influences have helped to shape his broad and rich worldview. He is inspired by Federico García Lorca’s rustic rawness, Frida Kahlo’s visual feminism, John Steinbeck’s earthy populism, Pablo Neruda’s lyricism, the Beat Generation’s inherent anarchism, the Teatro Campesino’s Chicano perspective, Malcolm X’s ideological determination, César Chávez’s social justice without violence, Carlos Santana’s pop-tinged tropical jazz, and the poet Alurista’s Meso-American soul and Spanglish idiom. Herrera indeed revolutionized poetry in the latter part of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first by expanding its contours, techniques, and passions, captivating his readers in the process.

Herrera’s first book, Rebozos of Love / We Have Woven / Sudor de Pueblos / On Our Back (l974), for example, offers haunting chants that conjure Indigenous voices and channel both cultural nationalism and Amerindian spirituality. A trilingual combination of Spanish, English, and Nahuatl suggests a new ethnic identity. Neologisms such as “solrainingotas” [sun + raining + drops], “maiztlán” [corn + the mythic homeland of the Aztecs], and “divinacóatl” [divine + Aztec serpent] leap off the page. Constructed as a free-flowing series of untitled poems, the book reads like one long, extended poem. In Exiles of Desire (l983), Herrera abandons the Indigenous utopia of his earlier book in order to face the harsh realities of crowded, urban barrios. In this volume of poems accompanied by photographs, he lays bare the tensions of life in exile within city walls, as in the poem “Your Name Is X.” In the 1980s, Herrera’s literary output included the experimental books A Night in Tunisia: Newtexts (l985), Facegames (l987), and Zenjosé: Scenarios (l988). The book that closes this period, the Central America–focused Akrílica (l989), is an expressionistic masterpiece, in which poetic “sketch cuts” represent moods and sentiments.

In the 1990s, Herrera’s work became at once more contemplative and more global in scope. In Memoria(s) from an Exile’s Notebook of the Future (1993), he considers the immigrant experience; in The Roots of a Thousand Embraces: Dialogues (1994), he offers a series of one-way imaginative dialogues with artist Frida Kahlo; and in Night Train to Tuxtla (1994), he reflects on the trajectory of his own life.

In the early years of the twenty-first century, Herrera focused primarily on expanding his craft. For instance, he began to write for young readers more frequently, publishing an acclaimed children’s book, The Upside Down Boy / El niño de cabeza (2000). Some of his poetic works of this period, such as Giraffe on Fire (200l), read more like inventive plays than poems. InNotebooks of a Chile Verde Smuggler (2002) and Half of the World in Light: New and Selected Poems (2008), recapitulated ideas about human life and society take on an incantatory quality. Cinnamon Girl: Letters Found in a Cereal Box (2005), a novel written for teen readers, confronts a most difficult topic: the horrors of 9/11.

In his recent writings, Herrera has been consumed with the topic of immigration and migration. This is especially evident in works such as Borderbus (2018) and Every Day We Get More Illegal (2020), in which he addresses stigmas, stereotypes, injustices, the human predicament, and the need to re-evaluate (im)migration as a world issue.

Juan Felipe Herrera is a writer of intense passion and commitment as well as a tireless innovator who blends poetry with other media to create new forms of expression. His legendary compassion favors the vulnerable and disenfranchised, and his extraordinary writings provide moving sketches of people struggling to survive.

Selected Bibliography

Flores, Lauro H. “Auto-referencialidad y subversión: observaciones (con)textuales en torno a la poesía de Juan Felipe Herrera.” Crítica 2 (Summer l990): 172–181.

Flores, Lauro H. “Juan Felipe Herrera (27 December 1948– ),” in Dictionary of Literary Biography: Chicano Writers, Second Series, ed. Francisco A. Lomelí and Carl R. Shirley. Detroit: A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book/Gale Research Inc., 1992, pp. 137–145.

Herrera, Juan Felipe. Rebozos of Love / We Have Woven / Sudor de Pueblos / On Our Back. San Diego: Toltecas de Aztlán Publications, 1974.

———. Akrílica. Santa Cruz, CA: Alcatraz Editions, l989.

———. Night Train to Tuxtla. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, l994.

———. Calling the Doves / El canto a las palomas. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press, l995. Illustrated by Elly Simmons.

———. Border-Crosser with a Lamborghini Dream. Tucson: University of Arizona, 1999.

———. Grandma & Me at the Flea / Los meros meros remateros. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press, 2002. Illustrated by Anita Lucio-Brock.

———. Cinnamon Girl: Letters Found Inside a Cereal Box. New York: HarperCollins-Joanna Cotler Books, 2005.

———.187 Reasons Mexicanos Can’t Cross the Border: Undocuments, l971– 2007. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2007.

———. Half of the World in Light: New and Selected Poems. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2008.

———. Senegal Taxi. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2013.

———. Every Day We Get More Illegal. San Francisco: City Lights Publishers, 2020.

Lomelí, Francisco A. “Forward / Juan Felipe Herrera: Trajectory and Metamorphosis of a Chicano Poet Laureate,” in Half of the World in Light: New and Selected Poems, by Juan Felipe Herrera. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2008, pp. xiv–xxiv.

Lomelí, Francisco A. “Forward / Juan Felipe Herrera: Trajectory and Metamorphosis of a Chicano Poet Laureate,” in Half of the World in Light: New and Selected Poems, by Juan Felipe Herrera. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2008, pp. xiv–xxiv.

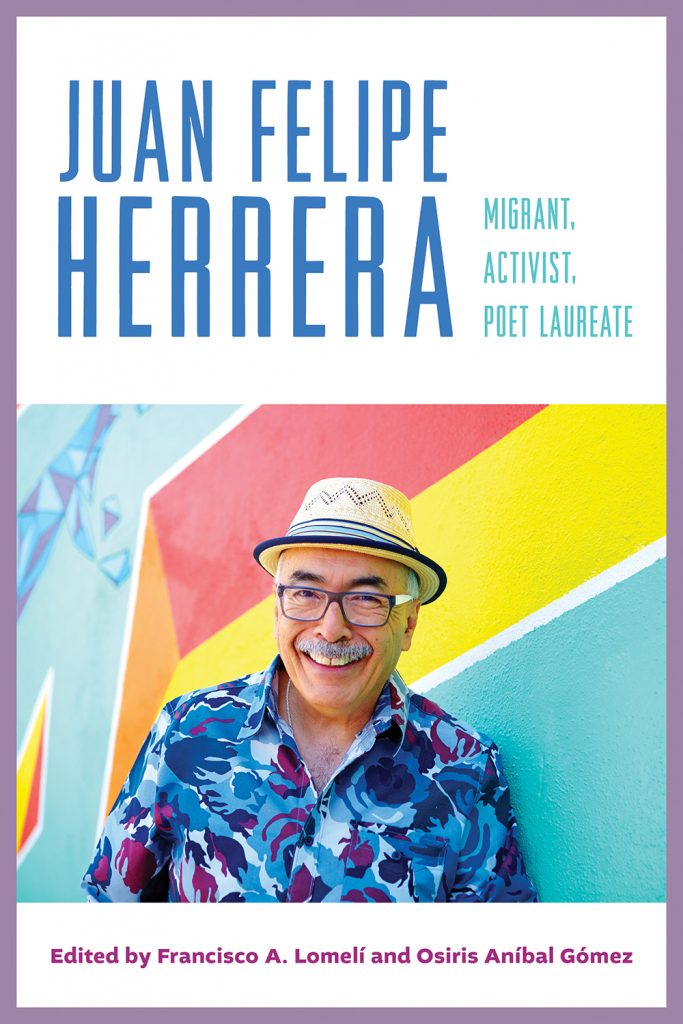

Lomelí, Francisco A., and Osiris A. Gómez, eds. Juan Felipe Herrera: Migrant, Activist, Poet Laureate. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, forthcoming 2023.

Soldofsky, Alan. “A Border-Crosser’s Heteroglossia: Interview with Juan Felipe Herrera; Twenty-First Poet Laureate of the United States.” MELUS: The Journal of the Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States 43.2 (June 2018): 196–226.Urrea, Luis Alberto. “A Rascuache Prayer: Reflections on Juan Felipe Herrera, My Homeboy Laureate.” Poetry Foundation. September l4, 2020. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/154196/a-rascuache-prayer.

Vaquera-Vásquez, Santiago. “Juan Felipe Herrera (1948).” In Latino and Latina Writers. vols. 1 and 2. Allan West-Durán, ed. New York: The Gale Group, 2004, pp. 281–298.

Francisco A. Lomelí is Professor Emeritus of Latin American Literature at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is the author, among other books, of Chicano Perspectives in Literature: A Critical and Annotated Bibliography (Pajarito Publications, 1976), and the co-editor of Juan Felipe Herrera: Migrant, Activist, Poet Laureate (forthcoming, University of Arizona Press, June 2023). The latter book is a major collection of essays that will offer new angles of vision on Herrera’s writings and assess his impact on contemporary literature, Chicano identity, and American history.