Voices of Democracy: Jovita Idár, the Idár Family, and the Struggle against Juan Crow

by Gabriela González

In August 2023, the US Mint will release the Jovita Idár quarter, “the ninth coin in the American Women Quarters Program” authorized by Public Law 116–330. On its website, the Mint states that Idár’s “ideas and practices were ahead of her time. She made it her mission to pursue civil rights for Mexican Americans and believed education was the foundation for a better future. Idár wrote many news articles in various publications speaking out about racism and supporting the revolution in Mexico.”

In August 2023, the US Mint will release the Jovita Idár quarter, “the ninth coin in the American Women Quarters Program” authorized by Public Law 116–330. On its website, the Mint states that Idár’s “ideas and practices were ahead of her time. She made it her mission to pursue civil rights for Mexican Americans and believed education was the foundation for a better future. Idár wrote many news articles in various publications speaking out about racism and supporting the revolution in Mexico.”

A bilingual and bicultural family, the Idárs participated as journalists in early twentieth-century transborder political movements focused on the procurement of rights for ethnic Mexicans. In Texas, they reported on the rise of Juan Crow segregation in schools and places of public accommodation. Sympathetic to the plight of labor, patriarch Nicasio Idár organized workers in Mexico in his youth. Years later, his eldest son, Clemente, worked for the American Federation of Labor, organizing ethnic Mexican workers in the United States. Nicasio’s daughter Jovita trained as a schoolteacher and worked briefly in this capacity. Exasperated by the segregated and substandard education afforded to ethnic Mexican schoolchildren in the early years of the twentieth century, she decided that she would be of greater service joining her father and brothers Clemente and Eduardo in the family newspaper, La Crónica. A muckraking paper, La Crónica exposed the underbelly of Texas society where ethnic Mexicans regularly experienced racism, discrimination, segregation, and increasing violence during a period known as La Matanza (the massacre) from 1910 to 1920.

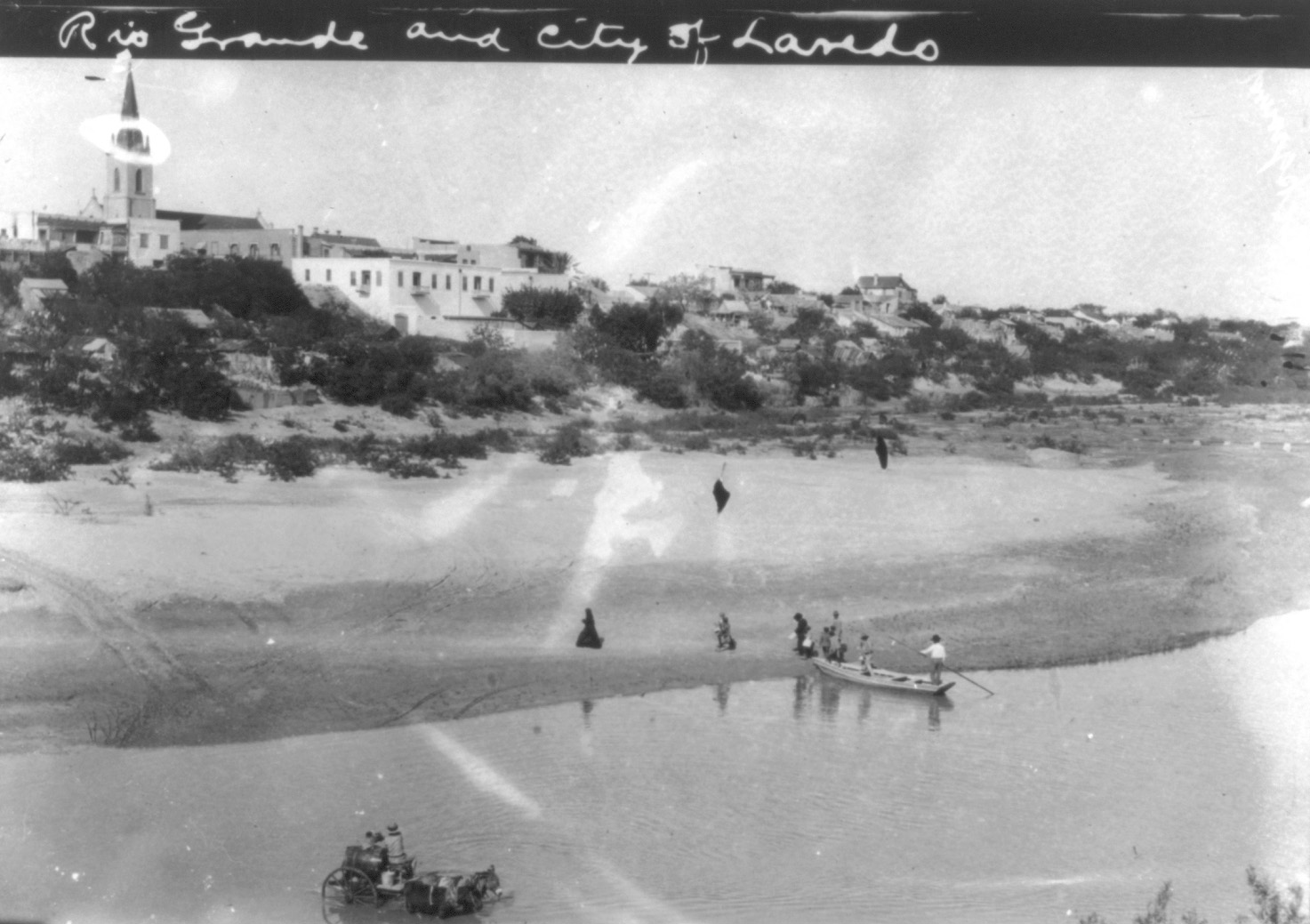

Indeed, the Idárs were early chroniclers of the growing dangers facing ethnic Mexicans in Texas. In addition to publishing exposés in La Crónica, in September 1911, the family organized El Primer Congreso Mexicanista (The First Mexicanist Congress) which addressed racism, segregation, lynching and other forms of violence, economic exploitation, and degradation of the Spanish language and Mexican culture. The ultimate goal of this congress was to unify all Mexican-origin people in Texas regardless of citizenship, because during the early twentieth century, US citizenship did not protect ethnic Mexicans from racial discrimination and potential violence. The weeklong conference, which took place in Laredo, Texas, attracted Mexican Americans, Mexican immigrants, and Mexican nationals, some of whom were members of assorted organizations such as fraternal orders, mutual aid societies, and labor unions. There were also journalists and women activists, whom Jovita Idár encouraged to attend.

Indeed, the Idárs were early chroniclers of the growing dangers facing ethnic Mexicans in Texas. In addition to publishing exposés in La Crónica, in September 1911, the family organized El Primer Congreso Mexicanista (The First Mexicanist Congress) which addressed racism, segregation, lynching and other forms of violence, economic exploitation, and degradation of the Spanish language and Mexican culture. The ultimate goal of this congress was to unify all Mexican-origin people in Texas regardless of citizenship, because during the early twentieth century, US citizenship did not protect ethnic Mexicans from racial discrimination and potential violence. The weeklong conference, which took place in Laredo, Texas, attracted Mexican Americans, Mexican immigrants, and Mexican nationals, some of whom were members of assorted organizations such as fraternal orders, mutual aid societies, and labor unions. There were also journalists and women activists, whom Jovita Idár encouraged to attend.

Women figured prominently in this human rights conference as speakers, and a group of them organized La Liga Feminil Mexanista (The League of Mexican Women) soon after. Led by Jovita Idár, this association attracted educated women such as the schoolteachers María Rentería and Berta Cantú. The women focused on benevolent and charitable projects, raising funds to help indigent families and providing free education for destitute children in Laredo.

Jovita Idár also cared about the poor and dispossessed in Mexico, serving as a nurse and member of La Cruz Blanca Mexicana (The Mexican White Cross) during the Mexican Revolution alongside her friend and White Cross founder, Leonor Villegas de Magnón. Women from northern Mexico and South Texas participated in the Mexican Revolution in myriad ways, from tending wounded rebel soldiers on the battlefield, to raising funds, to serving as newspaper journalists. Idár’s support of the rebel forces of General Venustiano Carranza inspired her to work for El Progreso, a pro-Carranza newspaper in Laredo. It was in this capacity that she confronted the Texas Rangers in 1914 when, under orders from Governor Oscar B. Colquitt, they set out to destroy the printing presses over an editorial published in El Progreso that was critical of President Woodrow Wilson’s militarization of the border and intervention in the revolution. When the Rangers arrived, they found Idár at the door, valiantly standing up in the name of freedom of speech and freedom of the press. The men retreated, only to return later to accomplish their mission when she was not present.

Idár and her family were committed to advocacy on behalf of ethnic Mexicans whose human rights were often violated in both Mexico and Texas. In Mexico the Idárs risked their lives in support of a revolution that toppled the thirty-plus-years’ dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, while in Texas they organized and worked with others to create the foundation for the modern Mexican American civil rights movement.

After moving to San Antonio in 1917, Idár served as a precinct judge in San Antonio’s Democratic Party. An active member of La Trinidad Methodist Church, she helped her community in San Antonio in myriad ways, especially through her work as an interpreter for Spanish-speakers at a county hospital and as a mentor to young people who sought her counsel. In 1917 she became co-editor of El Heraldo Christiano (The Christian Herald). She supported women’s suffrage and sought to educate Mexican American women about that struggle.

In 1929, Corpus Christi, Texas, witnessed the birth of the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), a national civil rights organization akin to the NAACP. Both Clemente and Eduardo Idár served as founding members. Eduardo also co-authored the LULAC Constitution and LULAC Code. The Code enshrined major principles of the Mexican American political mindset, encompassing calls for Americanization while encouraging respect for Mexican culture and a commitment to the struggle to dismantle Juan Crow in Texas and beyond.

In recent years, Jovita Idár’s story has been featured in two historical films. In 2020, an Imagen Award–winning short documentary about Idár was part of Unladylike 2020: The Changemakers, a series of digital shorts about twenty-six women trailblazers. In 2021, the documentary Citizens at Last: Texas Women Fight for the Vote put the spotlight on Idár as a champion of women’s suffrage. In 2020, Idár was the subject of an article in the “Overlooked No More” series in the New York Times. Other recent articles about Idár and her fight for human rights have appeared in Teen Vogue, Medium, The Texas Observer, and Texas Monthly, among other publications. A young adult book about women’s suffrage includes Idár and a children’s book focuses on her. Scholars have also explored the Idárs, having been introduced to this extraordinary family as early as 1974 by an article authored by Professor José E. Limón in the academic journal Aztlán. At present, I am working on a biography of Idár.

The scholarly interest in Idár and her family is not surprising, given how the struggle for rights has figured prominently in histories of the Mexican American experience. But what is it about her that has generated increasing interest and captured the public imagination even prior to the publication of a full-scale biography? Could it be that in our current time, plagued by various threats to democracy, we seek to learn from the example of those who stood up for democracy in bygone eras? Women of color, once ignored in history books or portrayed as peripheral, are now understood by a growing number of scholars to have played important roles in histories of democratic struggles.

I’ve had the privilege of reading and analyzing Jovita Idár’s democratic writings in her native Spanish, which captures her fervor and commitment to human rights. Sitting for hours in silent archival spaces, her words have permeated my mind, connecting me to a scholarly intellectual heritage I did not know about until I was in graduate school. In my historical imagination, there is a direct lineage stretching from the Idárs to LULAC, the American GI Forum, the Chicana/o movement, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), and the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project. I, too, am included in that lineage—a Mexican American student who graduated from high school, college, and graduate school, and who now teaches at a major research university, the University of Texas at San Antonio, a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI) whose very creation in 1969 is the direct result of human and civil rights activism.

The world beyond the humiliating Juan Crow discrimination that denied the humanity of ethnic Mexicans is a world that Jovita Idár, her family, and their political descendants worked to create. With much courage and fortitude, she and other women trailblazers stood up for democracy at great personal risk in their efforts to bring forth a more perfect union. For that, a grateful nation honors them in various ways, including with a series of special quarters.

The cries for justice from historically marginalized groups have had the salutary effect of keeping our democratic experiment alive and vibrant. Far from a spectator sport, democracy calls upon its participants to remain forever engaged, protecting their rights and the rights of others. It is this political commitment to one another, and not race, blood, or heritage, that makes us all Americans. E pluribus unum—Out of many, one!

In 2021, the City of Laredo renamed Bartlett Park the Jovita Idár El Progreso Park and developed a historical trail at this park to inform the public about Idár’s life and work. In addition, the city has commissioned a series of murals in her honor. Others are calling for schools in Laredo and San Antonio to be named after her. Thanks to the advocacy of Refusing to Forget project scholars and public intellectuals, a Texas Historical Commission marker commemorating Idár was erected in Laredo’s St. Peter’s Park in 2014. It is hoped that the next generation will not have to wait until graduate school to learn about this important voice of democracy.

Selected Bibliography

De León, Arnoldo, ed. War along the Border: The Mexican Revolution and Tejano Communities. College Station: Texas A&M Press, 2011.

González, Gabriela. Redeeming La Raza: Transborder Modernity, Race, Respectability, and Rights. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

González, Gabriela. “Jovita Idar: The Ideological Origins of a Transnational Advocate for La Raza.” In Texas Women: Their Histories, Their Lives, edited by Elizabeth Hayes Turner, Stephanie Cole, and Rebecca Sharpless, pp. 225–248. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015.

Hernández, Sonia. Working Women into the Borderlands. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2014.

Hernandez, Sonia, and John Morán González, eds. Reverberations of Racial Violence: Critical Reflections on the History of the Border. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2021.

Johnson, Benjamin H. Revolution in Texas: How a Forgotten Rebellion and Its Bloody Suppression Turned Mexicans into Americans. Yale University Press, 2003.

Limón, José E. “El Primer Congreso Mexicanista de 1911: A Precursor to Contemporary Chicanismo.” Aztlán 5, nos. 1–2 (Spring–Fall, 1974): 85–117.

Montejano, David. Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836 –1986. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986.

Muñoz Martinez, Monica. The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas. Harvard University Press, 2018.

Orozco, Cynthia E. No Mexicans, Women, or Dogs Allowed: The Rise of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009.

Zamora, Emilio, Cynthia Orozco, and Rodolfo Rocha, eds. Mexican Americans in Texas History. Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 2000.

Gabriela González is an associate professor of history at the University of Texas at San Antonio. She is the author of Redeeming La Raza: Transborder Modernity, Race, Respectability, and Rights (Oxford University Press, 2018), which won several book prizes, including the Coral Horton Tullis Memorial Prize for Best Book on Texas History and the Liz Carpenter Award for Best Book on the History of Women, both awarded by the Texas State Historical Association.