Bridging the Caribbean: Puerto Rican Roots in Nineteenth-Century America

by Virginia Sanchez Korrol

In recent years, the media has tended to portray US Latinos of Hispanic Caribbean ancestry as new immigrants, but this characterization ignores the long connections between these immigrants and the United States. And because Puerto Ricans, who have also had a prolonged presence in the United States, hold a non-immigrant status, their experiences have often been entirely excluded from accounts of US immigrant communities. In fact, the Hispanic Caribbean role in American history originated long before the nineteenth century, and it is well documented in recovered chronicles, letters, and other firsthand accounts and primary sources. These can be found in projects such as the "Recovering the US Hispanic Literary Heritage Project" of Arte Público Press and in published works such as the Memoirs of Bernardo Vega (1984).

In recent years, the media has tended to portray US Latinos of Hispanic Caribbean ancestry as new immigrants, but this characterization ignores the long connections between these immigrants and the United States. And because Puerto Ricans, who have also had a prolonged presence in the United States, hold a non-immigrant status, their experiences have often been entirely excluded from accounts of US immigrant communities. In fact, the Hispanic Caribbean role in American history originated long before the nineteenth century, and it is well documented in recovered chronicles, letters, and other firsthand accounts and primary sources. These can be found in projects such as the "Recovering the US Hispanic Literary Heritage Project" of Arte Público Press and in published works such as the Memoirs of Bernardo Vega (1984).

Vega’s Memoirs are an excellent starting place for studying the Puerto Rican experience in the United States. They also shed light on the immigrant experience and on community development and collaboration among Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Cubans, and other Latin Americans. Because Vega believed that "in order to stand on our own two feet, Puerto Ricans of all generations must begin by affirming our own history," he was determined to preserve that heritage. In his Memoirs, he reconstructed the evolution of a highly organized, vibrant Puerto Rican and pan-Latino community in the United States, which spanned almost a century from the 1860s to the 1950s. Vega’s detailed narrative was a first step in filling this gap in US history.

Vega describes a defining moment at "El Morito," a factory on 86th Street off New York City’s Third Avenue, where he was employed during the First World War. News of a pending strike in the Puerto Rican sugar industry electrified Vega’s fellow cigar workers, many of whom were Socialists. Engaged in heated discussion, the workers sought ways to rally in solidarity with the island workers. Among the group, one individual captured Vega’s attention. He was drawn by the man’s intense oratory, but also by his vaguely familiar countenance, and the fact that his surname was also Vega. The author describes his reactions to the other Vega:

While I listened to Antonio Vega I recalled how my father used to talk all the time about his lost brother, who had never been seen or heard from since he was very young. I’m not sure if it was the memory that did it, but I know I left deeply moved by the man who bore my last name. . . . When I went up to him he jumped to his feet with the ease of an ex-soldier and responded very courteously when I congratulated him for his speech. We then struck up a conversation at the end of which we hugged each other emotionally. He was none other than my father’s long lost brother.

The introduction into Vega’s memoirs of Tío Antonio, a man who arrives in New York at the age of nineteen in 1857 and resides in the city for over sixty years, is a significant point in the narrative. Antonio not only embodies the family lineage but evokes the heritage of all Puerto Rican emigrants to the continental shores well before the mid-twentieth century. Indeed as the story unfolds, Antonio becomes the face of countless Cubans, Dominicans, and Puerto Ricans who immigrated to the United States as artisans, labor leaders and laborers, professionals, political exiles, students, merchants, and travelers throughout the 1800s. Antonio’s broad knowledge of the small exile Caribbean community before and during the American Civil War, and his subsequent involvement in the US-based Antillean liberation movement, as well as his union and labor activism resonate with the experiences of hundreds of fellow expatriates. Although Vega was not an eyewitness to the events of this earlier era, he clearly intended to rescue historical antecedents from oblivion for the benefit of future generations.

Contacts, commerce, and communities formed the foundations of the earliest connections between the Hispanic Caribbean and what is today the United States. While the voyages of exploration chronicled by Cabeza de Vaca in 1537 and the founding of St. Augustine in 1565 initiated bonds between the islands and continental shores, the nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century expansion of commercial and diplomatic relations between Spain’s Caribbean colonies and trading houses in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York gave rise to identifiable Spanish-speaking communities. In 1808, El Misisipi became the first Spanish language newspaper to arise from US Latino communities. This publication, based in New Orleans, blazed a trail for the periodical literature that proliferated throughout the Spanish-speaking barrios of the nation.

That the first of the Spanish newspapers appeared in New Orleans was not surprising. That city, prominent in Caribbean politics, boasted supporters of both revolutionary action and the annexationist movements that reflected the interests of Southern slaveholders. Such sympathies account for Cuban trade disruptions of the Union blockade during the Civil War, as well as for the military support given to the Confederacy by hundreds of Cuban residents in Florida and Louisiana. Among those who supported the Confederate cause was Loreta Janeta Velazquez, who disguised herself as a man to fight for the South; the Harvard-educated diplomat José Agustín Quintero; and St. Augustine’s Sánchez sisters, who served as Confederate spies.

By 1825 the Hispanic Caribbean presence in the northeast included a Cuban exile community in New York City that espoused Antillean independence. From the smaller Cuban community in Philadelphia, activist Felix Varela published Jicotencal (1826), among the first historical novels written in the United States. Trade associations as well as literature emerged from the growing Latino communities. Commercial brokerage houses like the Cuban-Puerto Rican Benevolent Merchants’ Association, founded in 1830, reflected the growth of exchange networks during the antebellum years. By mid-century American ships laden with sugar and molasses from the Antilles often carried a second, human cargo of immigrants, who settled in continental port cities. In New York, a principal port of call, several waterfront boarding houses owned by Spanish-speaking entrepreneurs sheltered Hispanic Caribbean immigrants. These individuals, some 508, according to the federal census of 1845, found employment on merchant vessels, on the docks, and in local factories.

Trade and politics continued to bring a steady stream of merchants and prosperous visitors to the Northeast in the decades before the Civil War. A group of prominent Cuban families, the Quesadas, Arangos, and Mantillas, made their home on 110th Street facing Central Park, while the family of José de Rivera, a wealthy sugar and wine trader, settled into an elegant residence on Bridgeport, Connecticut’s Stratford Street. Although Rivera was one of the few Latinos in Connecticut in the 1850s, the 1860 census of New Haven, Connecticut, counted ten Puerto Ricans, one of whom, Augustus Rodríguez went on to fight in the Civil War.

Between 1868 and 1898, the growing intensity of political and economic conflicts in Latin America swelled expatriate communities in the northeast United States. And, in south Florida, insurgent exiles, unskilled and skilled workers, and unified cigar workers’ communities became the backbone of Antillean liberation efforts. Confronting oppressive colonial structures and the economic devastation wrought by the Ten Years’ War (1868–1878), Cubans spearheaded extensions of the island’s cigar industry in Tampa, Ybor City, and New York City, thus providing fertile ground for working-class immigration. These communities laid the foundations for the larger Antillean emigrations of the twentieth century.

Within these expatriate communities, intellectuals and activists addressed the issues of political independence and liberty within their homelands. In 1895 the Cuban and Puerto Rican Revolutionary Party, guided by José Martí, Francisco Gonzalo (Pachin) Marin, and Sotero Figueroa, drafted a radical statement, which was ratified by leading intellectuals, including philosopher-educator Eugenio María de Hostos, and the writers Lola Rodríguez de Tió and Emilia Casanova de Villaverde. The party’s goals were also endorsed by activist US- and Caribbean-based cells composed predominantly of working-class, multiracial men and women.

The outcome of the Spanish-Cuban-American War (1898) severed the close bonds and common agenda that had linked Cubans and Puerto Ricans throughout much of the nineteenth century. Within two years Cuba gained its independence, but Puerto Rico remained a colony of the United States. The passage of the Jones Act (1917) made Puertorriqueños American citizens and facilitated massive migration throughout the twentieth century. By 1900 half of the more than 7,500 Latin Americans in New York City came from the Hispanic Caribbean, primarily Puerto Rico. Their small but thriving community, well documented in Vega’s memoirs and in the collected essays of Jesús Colón (1982, 1993), boasted an energetic entrepreneurial spirit, manifested in boarding houses, small businesses, restaurants, grocery stores (bodegas), and a sense of community, which could be found in newspapers and presses, houses of worship, and a myriad of social and political groups. The 1923 Guia Hispana, a city guide to commercial and professional services, listed some 275 businesses and 150 professionals that catered to those professionals, entrepreneurs, and blue-collar workers like Colón, Vega, and his uncle Antonio who comprised the bulk of the Latino or Hispanic Caribbean community.

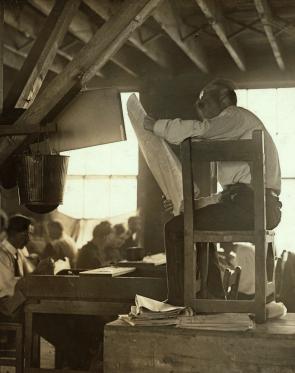

Among cigar workers the practice of La Lectura, reading aloud in the factories, honed class consciousness, awareness of workers’ struggles, and community solidarity. The only woman to read in the cigar factories, union activist Luisa Capetillo, personifies the level of involvement found in this community of workers between the two World Wars. Capetillo, who ran a vegetarian restaurant and boarding house on 22nd Street and Eighth Avenue, was a staunch advocate for the rights of women as well as the working class. Her writings rank among the earliest feminist discourses in modern America.

Today the Hispanic population of the United States continues to grow, spurred by economic and political developments in the Caribbean. During the 1960s the Puerto Rican population in the United States increased to one million, or 81 percent of all Latinos in New York City. And the Cuban Revolution (1959), the Dominican Civil War (1965), and the immigration reforms of 1965 all dramatically fueled an unprecedented increase among US Hispanic Caribbeans. But historians and students of history should remember that the story of Hispanic Caribbeans and their contributions to United States culture and society begins long before the mid-twentieth century.

Virginia Sánchez Korrol, Professor Emerita, Brooklyn College, The City University of New York, is the author of From Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in New York City (1994), Women in Latin America and the Caribbean (1999) with Marysa Navarro, and Teaching US Puerto Rican History (1999), and coeditor with Vicki Ruiz of Latina Legacies: Identity, Biography and Community (2005) and Latinas in the United States: A Historical Encyclopedia (2006).