Arturo Alfonso Schomburg: Archivist, Institution Builder, and Advocate of Global Black History

by Vanessa K. Valdés

“The American Negro must remake his past in order to make his future.” So begins one of the most well-known essays of the Harlem Renaissance, “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” written by Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. Published in the March 1925 Survey Graphic special issue dedicated to the New Negro and edited by Alain Locke, Schomburg impressed upon his readers the necessary recovery of a Black history of achievement that had been erased by a White supremacist insistence that such accomplishment never existed. It unfortunately remains a necessary argument.

“The American Negro must remake his past in order to make his future.” So begins one of the most well-known essays of the Harlem Renaissance, “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” written by Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. Published in the March 1925 Survey Graphic special issue dedicated to the New Negro and edited by Alain Locke, Schomburg impressed upon his readers the necessary recovery of a Black history of achievement that had been erased by a White supremacist insistence that such accomplishment never existed. It unfortunately remains a necessary argument.

The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, one of the four research libraries of the New York Public Library system, is the foremost archive of global Black history in the world. Yet its namesake remains a figure whose popularity has grown only recently. Schomburg’s journey from the Caribbean to New York City anticipates larger migratory waves that mark much of the twentieth century. He was born in San Mateo de Cangrejos (today Santurce), the only town founded by self-emancipated Black communities, in Puerto Rico, on January 24, 1874. This date marks ten months after the abolition of slavery in the Spanish colony. His mother, Mary Joseph, was a free Black woman whose family originated from the neighboring islands of the Danish West Indies. The Schomburgs were a Puerto Rican family of German heritage who had been on the island since the 1820s; little is known about the nature of the relationship of his parents. Raised in the capital of San Juan, he was told by a teacher in Puerto Rico that Black people had no history, thus planting the seed for his life’s project.

At seventeen years old, Schomburg moved to New York City, a space then populated by an Afro-Cuban and Afro-Puerto Rican exile community actively organizing and mobilizing for the independence of their homelands from Spain. He served as a secretary in a revolutionary club that he co-founded, Las Dos Antillas, and worked alongside his colleagues in the Partido Revolucionario Cubano, founded by José Martí and Rafael Serra. Their activities continued until the 1898 intervention by the United States in the third Cuban war for independence. Spain’s loss of its former colonies of Puerto Rico and Cuba to the United States meant widespread disillusion for many involved in those struggles for independence. For Schomburg, it meant continued immersion in African diasporic organizations.

In 1892, he was formally initiated into freemasonry in an Afro-Cuban lodge in Brooklyn, El Sol de Cuba Lodge, Number 38. The Prince Hall Masons would prove to be a powerful catalyst for Schomburg’s social mobility. This transnational fraternal order supported the advancement of Black men throughout this hemisphere. It supported autodidacts who could not access formal institutions of learning by providing structures for consistent self-education through study with each other. Schomburg’s participation in freemasonry identified him as a Race Man of the era, one whose focus was the progress of Black communities. As the demographics of the lodge changed from a hispanophone Caribbean membership to an anglophone one, Schomburg translated founding documents from Spanish to English, assisting and supporting his new brothers, and concerned himself with the preservation and maintenance of said documents. He gained renown within the world of the Prince Hall Masons, eventually being named Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge of the State of New York in 1926.

Throughout his life, Schomburg was resolutely focused on building institutions that promoted the progress of Black peoples. In 1911, he co-founded the Negro Society for Historical Research alongside his mentor John Edward Bruce. In 1914, he was admitted into the American Negro Academy, the first learned African American society, serving as its president from 1920 until 1928. He wrote for Carter G. Woodson’s Journal of Negro History, the publication of Woodson’s Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (today the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, the only such organization to survive the era). In each of these organizations, he focused on the contributions of communities of the African diaspora not only in the United States, but also throughout the world, including, importantly, Latin America and the Caribbean.

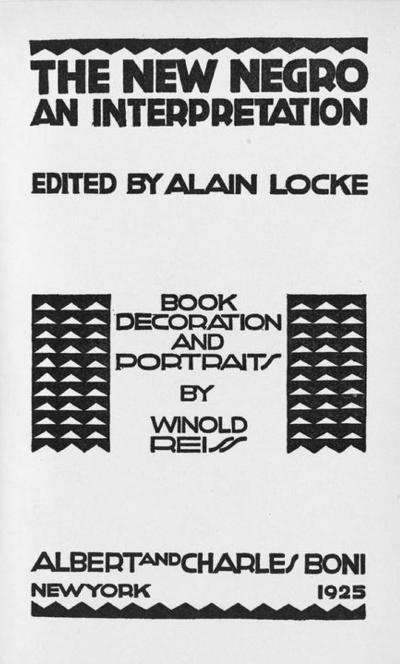

Schomburg was well aware of the importance of publishing. His name first appears in the public realm as “Arthur A. Schomburg” in a series of letters to the editor he wrote to the New York Times over the course of two years, from 1901 to 1903. They reveal a man deeply interested in both US domestic and foreign policy, with positions ranging from opposition to African American emigration movements to Africa, to support of Philippine revolutionaries chafing under US rule, to concern about the imposition of immigration laws on Puerto Rican subjects. In 1904 he published his first article, in commemoration of the centennial of Haiti’s independence. Over the decades, articles centering global Black history appeared in such important African American periodicals as the Crisis, Opportunity, and the Messenger. “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” published in the March 1925 special issue of Survey Graphic titled Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro, is an exhortation to Black peoples to recover narratives of their contributions to all societies in which they have lived. For Schomburg, history was a necessary tool in combatting White supremacist erasure. It was a means to restore that which had been removed by the lingering legacies of enslavement. The essay was reprinted a year later in the New Negro anthology edited by Alain Locke. Both publications mark a significant moment in the New Negro Renaissance, the modernist flowering of pride in Blackness as made manifest in several US cities, including New York and Chicago.

Schomburg was well aware of the importance of publishing. His name first appears in the public realm as “Arthur A. Schomburg” in a series of letters to the editor he wrote to the New York Times over the course of two years, from 1901 to 1903. They reveal a man deeply interested in both US domestic and foreign policy, with positions ranging from opposition to African American emigration movements to Africa, to support of Philippine revolutionaries chafing under US rule, to concern about the imposition of immigration laws on Puerto Rican subjects. In 1904 he published his first article, in commemoration of the centennial of Haiti’s independence. Over the decades, articles centering global Black history appeared in such important African American periodicals as the Crisis, Opportunity, and the Messenger. “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” published in the March 1925 special issue of Survey Graphic titled Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro, is an exhortation to Black peoples to recover narratives of their contributions to all societies in which they have lived. For Schomburg, history was a necessary tool in combatting White supremacist erasure. It was a means to restore that which had been removed by the lingering legacies of enslavement. The essay was reprinted a year later in the New Negro anthology edited by Alain Locke. Both publications mark a significant moment in the New Negro Renaissance, the modernist flowering of pride in Blackness as made manifest in several US cities, including New York and Chicago.

In that year, 1926, Schomburg sold his private collection to the Carnegie Corporation for $10,000 (approximately $177,000 in 2023) with the aim of donation to the 135th Street Branch library in New York City. Headed by chief librarian Ernestine Rose, this library was a central meeting place for intellectuals, scholars, and artists, and already featured a Division of Negro Literature, History, and Prints. Schomburg’s donation of more than ten thousand books, prints, musical scores, and other artifacts expanded its holdings exponentially, and became colloquially known as the Schomburg Collection. With his earnings, Schomburg traveled to Europe with the explicit intention of visiting archives, museums, and churches in order to identify and recover what he called “vindicating evidences” of Black contributions. He began his journey in Spain, with visits to Seville, Granada, and Madrid, before traveling to France, Belgium, and England. After his return in the fall of 1926, he wrote four articles detailing communities of African descent in Spain and highlighting exemplars of excellence. These exemplars included Juan Latino, a sixteenth-century professor of classics at the University of Granada, and Juan de Pareja, a seventeenth-century painter who, after being freed by his owner, Diego Velázquez, went on to thrive as an accomplished artist in his own right. In the late 1920s, Schomburg joined the staff of Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, traveling between New York and Nashville for several years. He developed Fisk’s library, which gained a local reputation for holdings pertaining to global Black communities. By 1932, he had returned to the 135th Street Branch, where he served as curator of his collection. He continued donating to the library until the end of his life. In 1972 it was renamed the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and recognized as a research library of the New York Public Library.

In that year, 1926, Schomburg sold his private collection to the Carnegie Corporation for $10,000 (approximately $177,000 in 2023) with the aim of donation to the 135th Street Branch library in New York City. Headed by chief librarian Ernestine Rose, this library was a central meeting place for intellectuals, scholars, and artists, and already featured a Division of Negro Literature, History, and Prints. Schomburg’s donation of more than ten thousand books, prints, musical scores, and other artifacts expanded its holdings exponentially, and became colloquially known as the Schomburg Collection. With his earnings, Schomburg traveled to Europe with the explicit intention of visiting archives, museums, and churches in order to identify and recover what he called “vindicating evidences” of Black contributions. He began his journey in Spain, with visits to Seville, Granada, and Madrid, before traveling to France, Belgium, and England. After his return in the fall of 1926, he wrote four articles detailing communities of African descent in Spain and highlighting exemplars of excellence. These exemplars included Juan Latino, a sixteenth-century professor of classics at the University of Granada, and Juan de Pareja, a seventeenth-century painter who, after being freed by his owner, Diego Velázquez, went on to thrive as an accomplished artist in his own right. In the late 1920s, Schomburg joined the staff of Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, traveling between New York and Nashville for several years. He developed Fisk’s library, which gained a local reputation for holdings pertaining to global Black communities. By 1932, he had returned to the 135th Street Branch, where he served as curator of his collection. He continued donating to the library until the end of his life. In 1972 it was renamed the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and recognized as a research library of the New York Public Library.

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg died in Brooklyn, New York, on June 10, 1938, at the age of sixty-four, after an unexpected illness. He is buried in Cypress Hill Cemetery. He was survived by seven children: Arthur Alfonso, Jr. (b. 1898–unknown) and Kingsley Guarionex (1900–1997), born to Elizabeth (Bessie) Hatcher; Reginald Stanton (1903–1982) and Nathaniel José (1907–1992), born to Elizabeth J. Morrow; and Fernando Alfonso (1912–1990), Dolores Maria (1914–1994), and Carlos Plácido (1916–unknown), born to Elizabeth Green. His first child, Maximo Gomez, died within months of his birth in 1897.

Vanessa K. Valdés is associate provost for community engagement and professor of Spanish and Portuguese at the City College of New York. She is the author of Diasporic Blackness: The Life and Times of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (SUNY Press, 2017).