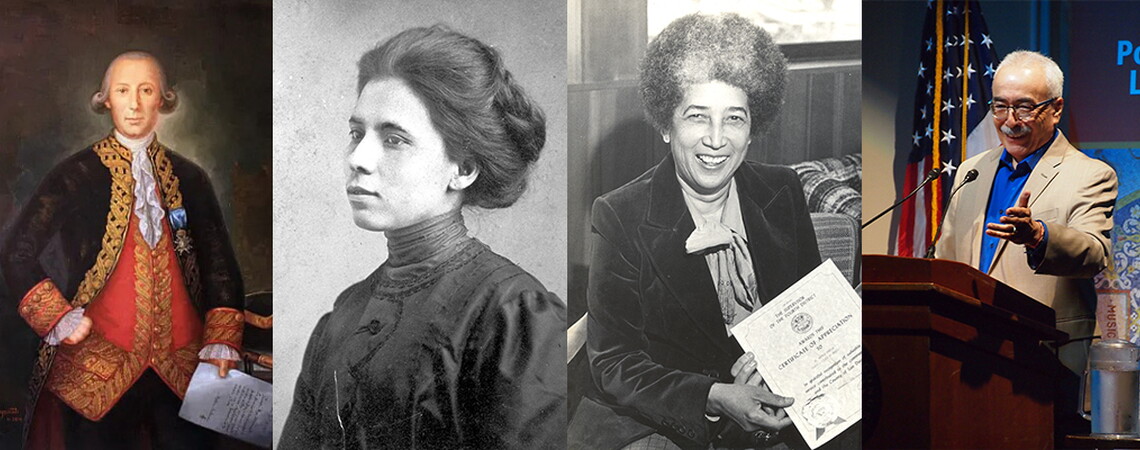

El enemigo de mi enemigo es mi amigo: Bernardo de Gálvez and the Battle That Saved the United States at Its Birth

by Larrie D. Ferreiro

“The enemy of my enemy is my friend,” goes the old adage, which is particularly apt when describing the relationship between Spain and the nascent United States during the War of American Independence. By 1775 when the war began, Britain, Spain, and France had been fighting for more than a century for control of North America, gradually displacing the First Nations whose territories they conquered. The Seven Years’ War (1754–1763, also called the French and Indian War) was pivotal in this long conflict, for by its end, Britain had taken Canada from France and Florida from Spain, and now “ruled the waves,” as the song declares. France and Spain, who were allied by a military treaty called the Bourbon Family Compact (their kings were cousins, both descended from Louis XIV), together vowed revenge against the British. As they planned their counterattack, they began searching for ways to exploit the growing unrest in the American colonies, as a way to weaken Britain in preparation for another war.

“The enemy of my enemy is my friend,” goes the old adage, which is particularly apt when describing the relationship between Spain and the nascent United States during the War of American Independence. By 1775 when the war began, Britain, Spain, and France had been fighting for more than a century for control of North America, gradually displacing the First Nations whose territories they conquered. The Seven Years’ War (1754–1763, also called the French and Indian War) was pivotal in this long conflict, for by its end, Britain had taken Canada from France and Florida from Spain, and now “ruled the waves,” as the song declares. France and Spain, who were allied by a military treaty called the Bourbon Family Compact (their kings were cousins, both descended from Louis XIV), together vowed revenge against the British. As they planned their counterattack, they began searching for ways to exploit the growing unrest in the American colonies, as a way to weaken Britain in preparation for another war.

The American colonists knew of the enmity of France and Spain against Britain, and even before fighting broke out in 1775, they were asking Spanish merchants, with whom they had been trading cod and other victuals for decades, to help provide muskets and gunpowder for their rebellions against their British rulers. Diego de Gardoqui and other merchants covertly smuggled arms, munitions, and supplies to America, though with the tacit support of Spain’s King Carlos III and his prime minister the Conde de Floridablanca. Meanwhile, Spanish observers from Cuba and New Orleans traveled as far north as New York to report on the state of the Revolution. All of this information was fed back to Madrid, as the Spanish and French crowns began girding for war against Britain.

The Spanish government was therefore fully prepared to help the United States when it declared independence in July 1776, but only by arming the American insurgents—it was not yet ready for open warfare. José de Gálvez, the powerful minister of the Indies who oversaw the Spanish territories from Mexico and the Caribbean to Chile, ordered the government of Spanish Louisiana in New Orleans to send arms and supplies up the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers to American forces in the western territories, so as to keep the British on the back foot. That order was readily followed, for in 1777 José de Gálvez had appointed his nephew Bernardo de Gálvez as governor and military commander of Louisiana. Bernardo de Gálvez was just thirty-one years old at the time, but already a skilled soldier and administrator. At the age of sixteen he had fought in the Seven Years’ War, and four years later he had accompanied his uncle to Mexico to reform the colonial government. Young Bernardo had also led a series of expeditions to secure Spanish settlements against attacks by Native American nations.

Bernardo de Gálvez, as governor of Louisiana, not only provisioned American troops, but also began building up his own military strength and spying on the British fortifications in West Florida. He knew that war was coming, and he intended to recapture the whole colony for Spain. In 1776 and 1777, Spain and France together had supplied arms and munitions to keep the Americans—who had almost no manufacturing capability for cannon, gunpowder, or muskets—in the fight against Britain. By September 1777, they had supplied the Continental Army with enough weapons to defeat the British at the Battles of Saratoga, the first major strategic victory for the American forces.

In February 1778, France signed a treaty with the United States and immediately acted on its new military alliance by declaring war on the British and sending an expedition to fight them in New England and Georgia. Although Spain was allied with France, it was not yet ready to go to war with Britain—its last silver fleet was still at sea, vulnerable to attack by the Royal Navy. After that fleet arrived in port, Spain signed a new military treaty with France in April 1779 and declared war on Britain. Carlos III and Floridablanca did not want a direct alliance with the United States. Spain was a colonial monarchy, after all, and the model of an American republic was a tangible threat to the Spanish empire. However, Spain did agree to keep fighting until Britain recognized the independence of the United States. Spain and the United States, though not allies, became friends by virtue of having a common enemy.

In February 1778, France signed a treaty with the United States and immediately acted on its new military alliance by declaring war on the British and sending an expedition to fight them in New England and Georgia. Although Spain was allied with France, it was not yet ready to go to war with Britain—its last silver fleet was still at sea, vulnerable to attack by the Royal Navy. After that fleet arrived in port, Spain signed a new military treaty with France in April 1779 and declared war on Britain. Carlos III and Floridablanca did not want a direct alliance with the United States. Spain was a colonial monarchy, after all, and the model of an American republic was a tangible threat to the Spanish empire. However, Spain did agree to keep fighting until Britain recognized the independence of the United States. Spain and the United States, though not allies, became friends by virtue of having a common enemy.

“El enemigo de mi enemigo” was also the dictum by which Bernardo de Gálvez operated. As soon as word of Spain’s declaration of war reached New Orleans in July 1779, Gálvez gathered his Regimiento Fijo de La Luisiana (Fixed Regiment of Louisiana) and militia to march on Baton Rouge and Natchez, the first of several British garrisons he would conquer on his route to recapture West Florida. His 667 troops included nine American volunteers under the merchant Oliver Pollock, the man who created the dollar sign ($), though Gálvez eschewed any idea of fighting alongside the Continental Army or state militia. His first victories were fairly quick. The siege of Baton Rouge lasted just two weeks, and by September, the British had surrendered much of the lower Mississippi to the Spanish.

The next target, Mobile, would prove harder to take. Gálvez departed New Orleans in early January 1780, but violent storms and difficulties navigating the marshy terrain meant that the Regimiento Fijo did not reach Mobile until late February. As the Spanish laid in a weeks-long siege, Gálvez and the British commander Elias Durnford exchanged correspondence and even gifts, a mark of the chivalry that befitted both commanders. Gálvez spoke no English, so wrote in French to offer Durnford the possibility of surrender without casualties. Durnford politely declined but sent mutton, wine, and chickens; Gálvez replied with oranges, cigars, and more wine. All the while the siege dragged on, reducing Mobile to rubble, until Dunford finally capitulated in March 1780. Pensacola, the capital of British West Florida, was now firmly in Gálvez’s sights, but another series of devastating storms prevented the Spanish fleet from departing until February 1781.

On March 18, Gálvez stood aboard his presumptuously named sloop Galveztown before the heavily guarded entrance to Pensacola Bay. To show the rest of his fleet that there was nothing to fear from British cannon, he crossed the entrance under heavy fire, exclaiming, “I alone (yo solo) went to sacrifice myself.” The other warships sailed unharmed into the bay, where they unloaded troops and cannon to begin the Siege of Pensacola, which would last two months. On May 8, 1781, exhausted and almost out of supplies, Spanish artillery fired a lucky shot that exploded the ammunition magazines at the Queen’s Redoubt to terrible effect. Gálvez’s troops stormed the British fortifications, and by nightfall he was negotiating the British surrender of all West Florida.

![Detail from "Prise de Pensacola" [Capture of Pensacola and explosion at the Queen’s Redoubt], engraving by Nicolas Ponce after a drawing by Lausan, 1784 (New York Public Library)](/sites/default/files/2023-03/PrisePensacola_NYPL.jpg)

Gálvez’s victory at the Battle of Pensacola meant far more than the mere capture of a spit of land. In April 1781 a large French fleet under Admiral Comte de Grasse had arrived in the Caribbean. His orders were to protect the French colonies like Martinique, but for a few months during hurricane season—September through November—he was free to help the combined American and French armies (under, respectively, Generals Washington and Rochambeau) in America. When he received messages to meet them at Yorktown in Chesapeake Bay, he planned to leave several ships in the Caribbean to protect the colonies. But with the British out of West Florida, Spain now controlled the Gulf of Mexico and much of the Caribbean, and offered to protect the French colonies, allowing de Grasse to take his entire fleet north. De Grasse encountered a British fleet off the Chesapeake Capes on September 5 and won a closely fought battle, which kept the Chesapeake Bay secure and allowed Washington and Rochambeau to defeat the British at the Siege of Yorktown. Gálvez’s victory at Pensacola allowed de Grasse’s victory at the Chesapeake, which in turn ensured the French-American victory at Yorktown. Although the fighting would continue for another two years, in September 1783 Britain surrendered and recognized the independence of the United States—one of the conditions Spain had set for ultimate victory.

Soon afterwards, Bernardo de Gálvez became viceroy of New Spain (today’s Mexico) and established his home just outside Mexico City at Chapultepec Castle, the grounds of which were decorated with his new family motto “Yo Solo.” But he did not live to see it completed, dying from dysentery in 1786 at age forty. Although Bernardo de Gálvez never visited the new United States of America, the ship that bore his name—Galveztown—was present in New York City when George Washington was inaugurated president in April 1789. When Galveztown saluted with its cannon, it was, perhaps, as if Gálvez’s own voice boomed across the harbor in celebration. His exploits helped bond Spain and America in a friendship, based not on a common enemy, but on common interests.

Recommended Reading

Chávez, Thomas E. Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002.

DuVal, Kathleen. Independence Lost: Lives on the Edge of the American Revolution. New York: Random House, 2015.

Ferreiro, Larrie D. Brothers at Arms: American Independence and the Men of France and Spain Who Saved It . New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016.

Quintero Saravia, Gonzalo M. Bernardo de Gálvez: Spanish Hero of the American Revolution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Reparaz, Carmen de. I Alone: Bernardo de Gálvez and the Taking of Pensacola in 1781: A Spanish Contribution to the Independence of the United States . Madrid: Ediciones De Cultura Hispánica, 1993.

Larrie D. Ferreiro received his PhD in the History of Science and Technology from Imperial College London. He teaches history and engineering at George Mason University, Georgetown University, and the Stevens Institute of Technology. He is the author of Brothers at Arms: American Independence and the Men of France and Spain Who Saved It (Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in History.