Self-Evident Truths: Black Americans and the Declaration of Independence

by Leigh Fought

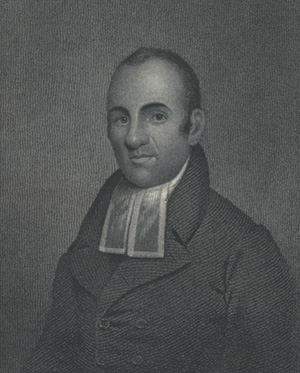

In 1776, as the ink on the Declaration of Independence dried, the Rev. Lemuel Haynes pointed out that Black Americans like himself lived under “much greater oppression than that which Englishmen seem so much to spurn at. I mean an oppression which they, themselves, impose upon others.”[1] The final negotiations on the Treaty of Paris in 1783 had barely concluded when “Vox Africanorum” (“Voice of the Africans”), the pen name of a Black Maryland editorialist, exclaimed, “Let America cease to exult—she has yet obtained but partial freedom.”[2] Those enslaved by the author of the Declaration of Independence discovered too well what that Maryland writer meant. When Thomas Jefferson died fifty years to the day after the Declaration’s adoption, 130 Black people faced the auction block on the steps of Monticello to pay off his debts. Twenty-six years later, on July 5, 1852, Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass reflected on the national celebrations of the previous day and asked, “Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us?” After all, “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?”[3]

In 1776, as the ink on the Declaration of Independence dried, the Rev. Lemuel Haynes pointed out that Black Americans like himself lived under “much greater oppression than that which Englishmen seem so much to spurn at. I mean an oppression which they, themselves, impose upon others.”[1] The final negotiations on the Treaty of Paris in 1783 had barely concluded when “Vox Africanorum” (“Voice of the Africans”), the pen name of a Black Maryland editorialist, exclaimed, “Let America cease to exult—she has yet obtained but partial freedom.”[2] Those enslaved by the author of the Declaration of Independence discovered too well what that Maryland writer meant. When Thomas Jefferson died fifty years to the day after the Declaration’s adoption, 130 Black people faced the auction block on the steps of Monticello to pay off his debts. Twenty-six years later, on July 5, 1852, Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass reflected on the national celebrations of the previous day and asked, “Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us?” After all, “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?”[3]

Whether they claim United States citizenship through birthright or naturalization, Americans today base their concept of freedom on the words of the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.”[4] Such words had real power in the world. They created the nation as a state and as a people. They also formed an ethical ideology and language that transcended race and status. Yet, as “A Free Negro” in Maryland asked in 1789, “do rights of nature cease to be such, when a negro is to enjoy them?”[5] African Americans realized the central hypocrisy in the founding of the nation and used the shared values expressed in the Declaration of Independence to force White Americans to justify their continued participation in the transatlantic slave trade and the institution of slavery itself.

African Americans initially addressed those who had the power to effect change. In 1777, a group of Black Bostonians petitioned the new Massachusetts legislature to enact statewide emancipation. They pointed to the new state constitution that included wording similar to the Declaration of Independence, arguing that enslaved people had “in common with all other Men, a natural and unalienable right to that freedom, which the great Parent of the Universe hath bestowed equally on all Mankind.”[6] Similar petitions appeared before legislatures in New Hampshire and Connecticut in 1779. The Massachusetts Assembly tabled the 1777 proposal, but in the 1780s, the cases of Quock Walker and Elizabeth Freeman effectively ended the institution in the state. Freeman, enslaved in western Massachusetts, had attended a public recitation of the Declaration of Independence and approached an attorney to file a freedom suit on her behalf. “I heard that paper read yesterday, that says, all men are born equal, and that every man has a right to freedom,” she told him, bluntly stating the obvious: “I am not a dumb critter; won’t the law give me my freedom?”[7]

African Americans initially addressed those who had the power to effect change. In 1777, a group of Black Bostonians petitioned the new Massachusetts legislature to enact statewide emancipation. They pointed to the new state constitution that included wording similar to the Declaration of Independence, arguing that enslaved people had “in common with all other Men, a natural and unalienable right to that freedom, which the great Parent of the Universe hath bestowed equally on all Mankind.”[6] Similar petitions appeared before legislatures in New Hampshire and Connecticut in 1779. The Massachusetts Assembly tabled the 1777 proposal, but in the 1780s, the cases of Quock Walker and Elizabeth Freeman effectively ended the institution in the state. Freeman, enslaved in western Massachusetts, had attended a public recitation of the Declaration of Independence and approached an attorney to file a freedom suit on her behalf. “I heard that paper read yesterday, that says, all men are born equal, and that every man has a right to freedom,” she told him, bluntly stating the obvious: “I am not a dumb critter; won’t the law give me my freedom?”[7]

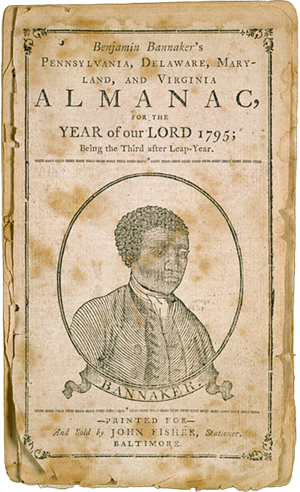

Not all states proved open to such arguments so quickly, particularly farther south along the seaboard. Free Baltimorean Benjamin Banneker, like Freeman, felt it necessary to protest that Black Americans “have long been considered rather as brutish than human, and scarcely capable of mental endowments.” In writing those words to Thomas Jefferson in 1791, Banneker sent him a copy of his Almanac, approaching Jefferson as a fellow man of reason and science. As secretary of state and the man who penned the very words that established a nation, Jefferson was in a position of influence and credibility to address emancipation. “I hope you cannot but acknowledge, that it is the indispensable duty of those, who maintain for themselves the rights of human nature,” insisted Banneker, “to extend their power and influence to the relief of every part of the human race, from whatever burden or oppression they may unjustly labor under.”[8]

Not all states proved open to such arguments so quickly, particularly farther south along the seaboard. Free Baltimorean Benjamin Banneker, like Freeman, felt it necessary to protest that Black Americans “have long been considered rather as brutish than human, and scarcely capable of mental endowments.” In writing those words to Thomas Jefferson in 1791, Banneker sent him a copy of his Almanac, approaching Jefferson as a fellow man of reason and science. As secretary of state and the man who penned the very words that established a nation, Jefferson was in a position of influence and credibility to address emancipation. “I hope you cannot but acknowledge, that it is the indispensable duty of those, who maintain for themselves the rights of human nature,” insisted Banneker, “to extend their power and influence to the relief of every part of the human race, from whatever burden or oppression they may unjustly labor under.”[8]

The shaming implicit in Banneker’s words became more explicit with the delay of emancipation in northern states other than Pennsylvania and Massachusetts and the clear reluctance to consider even the most gradual plans in the South. “In what light can the people of Europe consider America after the strange inconsistency of her conduct?” asked another Maryland editorialist, “Othello,” in May 1788.[9] Even in the absence of universal White male suffrage, participation in civic life on election days, Fourth of July celebrations, and the press gave force to public opinion. As other disfranchised groups, such as women and working-class men, expressed themselves in these venues, so too could African Americans in urban areas whether they were free or enslaved. While July Fourth could be an occasion to protest slavery and inequality, which early abolitionist societies did by the 1790s, some turned to alternate days as more fitting to celebrate. The end to the transatlantic slave trade on January 1, 1808, state emancipation days, Bastille Day, or, later during the abolitionist movement, West Indian Emancipation Day on August 1, 1834, all became days to reference the Declaration of Independence as a promise unfulfilled.

The Declaration of Independence also outlined an argument for justified rebellion. “When a long train of Abuses and Usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a Design to reduce them under absolute Despotism,” Jefferson had written, “it is their Right, it is their Duty, to throw off such Government.”[10] In 1800, in Richmond, Virginia, enslaved artisans led by the blacksmith Gabriel planned to march on the state capital. Like the Massachusetts petitioners, they appealed directly to state power. Unlike the petitioners, they had few other avenues to enact broad change toward liberty. Their uprising was to take place on August 30, but the plans were discovered and Gabriel and twenty-five of his co-conspirators were put to death. More often, however, Black abolitionists used the right of rebellion as a threat, with the revolution in Saint-Domingue providing precedent. During Fourth of July celebrations in New York in 1804, for example, Black Americans invoked the Saint-Domingue revolution as a counterpoint to the American Revolution after being harassed by White Americans. By 1829, David Walker echoed the arguments of the preceding fifty-three years, quoted the Declaration on the right to rebellion, then warned White Americans not to deceive themselves that “we will never throw off your murderous government, and ‘provide new guards for our future security.’”[11]

The United States finally did eliminate the contradiction of slavery in 1865, but the question shifted to the underlying problem of racial inequality. More than a century after Frederick Douglass asked whether Black Americans were included in the promises of America, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. stood on the steps of a monument to the man who issued the Emancipation Proclamation and likened the Declaration to a “promissory note” that had yet to be fulfilled.[12] King’s sentiments echoed in the words of then-Senator Barack Obama forty-five years later as he spoke in the shadow of Independence Hall, the site of the Declaration’s signing, and proclaimed its work “ultimately unfinished” because “it was stained by this nation’s original sin of slavery.”[13] Even after Obama’s historic presidency and while a Black woman, descended from enslaved people, holds the vice presidency, the first Black woman to sit on the Supreme Court issued an impassioned statement against “race-based gaps” in “the health, wealth, and well-being of American citizens” that could be traced back through a history of segregation and bondage. Writing in the tradition of those African-descended Americans before her, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson invoked to the Declaration of Independence to call for equity because “every moment these gaps persist is a moment in which this great country falls short of actualizing one of its foundational principles—the ‘self-evident’ truth that all of us are created equal.”[14] These are powerful ideas that created a nation, and that every African American since has called upon to make it “more perfect.”

Recommended Reading

Adams, Catherine, and Elizabeth H. Pleck. Love of Freedom: Black Women in Colonial and Revolutionary New England. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Berry, Daina Ramey, and Kali Nicole Gross. A Black Women’s History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2020.

Nash, Gary B. The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America. New York: Penguin, 2005.

Sinha, Manisha. The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

Waldstreicher, David. In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes: The Making of American Nationalism, 1776–1820. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Leigh Fought is an associate professor of history at Le Moyne College. She is the editor of The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series Three: Correspondence, Volume I: 1842–1852 (Yale University Press, 2009), and author of Southern Womanhood and Slavery: A Biography of Louisa S. McCord (University of Missouri Press, 2003) and Women in the World of Frederick Douglass (Oxford University Press, 2017).

[1] Lemuel Haynes, “Liberty Further Extended: Or Free Thoughts on the Illegality of Slave-Keeping” (1776).

[2] “Vox Africanorum,” Letter to the Maryland Gazette (May 15, 1783).

[3] Frederick Douglass, Oration, Delivered in Corinthian Hall, Rochester . . . July 5th, 1852 (Rochester: Lee, Mann & Co., 1852), pp. 14, 20. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC06829. A pdf with excerpts is linked here.

[4] Declaration of Independence, printed by Peter Timothy in Charleston, South Carolina, ca. August 2, 1776. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC00959.

[5] “A Free Negro,” letter on slavery to the American Museum, vol. 5, p. 77 (1789), reprinted in “What the Negro Was Thinking during the Eighteenth Century,” Journal of Negro History 1, No. 1 (January 1916): 49–67, p. 65, HathiTrust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/emu.010000158346.

[6] Lancaster Hill, Peter Bess, Brister Slenser, Prince Hall, et al., “The Petition of a Great Number of Negroes Who Are Detained in a State of Slavery,” Boston, Massachusetts, January 13.

[7] Elizabeth Freeman [“Mum-Bett”], quoted in Catharine Maria Sedgwick, “Slavery in New England” (Bentley's Miscellany, vol. 34, 1853, pp. 417–24), p. 421, reprinted online in Sedgwick Stories: The Periodical Writings of Catharine Maria Sedgwick, sedgwickstories.omeka.net/items/show/58.

[8] Benjamin Banneker, Copy of a Letter . . . To the Secretary of State, with His Answer (Philadelphia, 1791), pp. 4 and 5, reprinted in Founders Online. National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-22-02-0049.

[9] Anonymous [“Othello”], “Essay on Negro Slavery, No. 1,” in the American Museum, Vol. 4, pp. 412–415 (May 10, 1788), reprinted in “What the Negro Was Thinking During the Eighteenth Century,” Journal of Negro History, Vol. 1, No. 1 (January 1916): 49–67, p. 50. HathiTrust, hdl.handle.net/2027/emu.010000158346.

[10] Declaration of Independence, printed by Peter Timothy in Charleston, South Carolina, ca. August 2, 1776. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC00959.

[11] David Walker, Walker’s Appeal, in Four Articles; Together with a Preamble, to the Coloured Citizens of the World (Boston, 1830), p. 78, reprinted online in Documenting the American South, docsouth.unc.edu/nc/walker/walker.html.

[12] Martin Luther King, Jr., “I Have A Dream” speech at the March on Washington, August 28, 1963.

[13] Barack Obama, speech on race, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, March 18, 2008. NPR, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=88478467.

[14] Ketanji Brown Jackson, dissenting, Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina, June 29, 2023, p. 1. The Hill, https://thehill.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/06/Jackson-dissent.pdf.