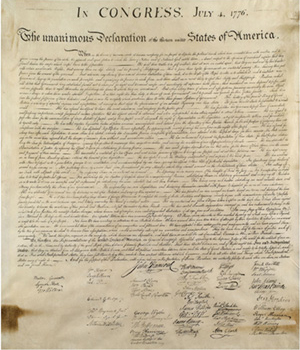

The Declaration of Independence as Mission Statement in the Age of Lincoln

by Adam I. P. Smith

At Gettysburg in 1863, Abraham Lincoln made the Declaration of Independence the moment of creation for the American republic from which all else had proceeded. In some mystical sense, the nation had been “conceived” in liberty and dedicated—in some kind of baptism—to the “proposition” that all men were created equal. If the Confederacy triumphed, Lincoln claimed, the first and only attempt in human history to found a nation on those ideals would have failed, and humanity would enter a new era of darkness—government of, by, and for the people would perish, forever.[1]

At Gettysburg in 1863, Abraham Lincoln made the Declaration of Independence the moment of creation for the American republic from which all else had proceeded. In some mystical sense, the nation had been “conceived” in liberty and dedicated—in some kind of baptism—to the “proposition” that all men were created equal. If the Confederacy triumphed, Lincoln claimed, the first and only attempt in human history to found a nation on those ideals would have failed, and humanity would enter a new era of darkness—government of, by, and for the people would perish, forever.[1]

Lincoln was a hugely gifted wordsmith, and his Address at Gettysburg was admired at the time for its ringing clarity. But just as Thomas Jefferson claimed that the Declaration he drafted was merely an emanation of the “American mind,” Lincoln argued that the ideas of America he expressed at Gettysburg were no more than the mainstream assumptions of mid-nineteenth-century Americans, or at least of a majority of those living in the free states.[2] Supportive newspapers praised it as “appropriate” and “eloquent” even while observing that Lincoln’s claim about the centrality of the Declaration was something that all his listeners already understood. As those newspaper responses indicated, Lincoln was by no means the first to hail the Declaration’s preamble as the nation’s moment of origin, but the fame of the Gettysburg Address can obscure the multiple layers of meanings that antebellum and Civil War Americans attached to Jefferson’s document.

![Congressman John Petitt of Indiana, an egraving from "McClees' Gallery of Photographic Portraits of the Senators, Representatives & Delegates of the Thirty-Fifth Congress (Washington: McClees & Beck, [1859]), based on a photograph by Julian Vannerson (Library of Congress)](/sites/default/files/2023-07/JohnPetitt1859_LOC.png) Abolitionists like Frederick Douglass were savagely effective at contrasting the Declaration’s ringing proclamation of equality with the reality of slavery. In response, some northern conservatives rejected the Declaration entirely. Indiana Democratic senator John Pettit called the proposition that all men are created equal a “self-evident lie” during a debate on the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854.[3] There was also a now little-remembered mid-nineteenth-century movement that rejected the universalism of Enlightenment thinking wholesale. In the 1840s and ’50s, one of the most prominent advocates for this reactionary position was the president of Dartmouth College, the Reverend Nathan Lord, a man reared in a strict Calvinist tradition who had once been an antislavery advocate but had come to believe that slavery, like other forms of hierarchy and domination, were part of God’s natural order. Thomas Jefferson, wrote Lord, had succumbed to the “illuminism and cosmopolitanism of his times, and embodied his chimera in the ‘glittering generalities’ of the Declaration of Independence.”[4]

Abolitionists like Frederick Douglass were savagely effective at contrasting the Declaration’s ringing proclamation of equality with the reality of slavery. In response, some northern conservatives rejected the Declaration entirely. Indiana Democratic senator John Pettit called the proposition that all men are created equal a “self-evident lie” during a debate on the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854.[3] There was also a now little-remembered mid-nineteenth-century movement that rejected the universalism of Enlightenment thinking wholesale. In the 1840s and ’50s, one of the most prominent advocates for this reactionary position was the president of Dartmouth College, the Reverend Nathan Lord, a man reared in a strict Calvinist tradition who had once been an antislavery advocate but had come to believe that slavery, like other forms of hierarchy and domination, were part of God’s natural order. Thomas Jefferson, wrote Lord, had succumbed to the “illuminism and cosmopolitanism of his times, and embodied his chimera in the ‘glittering generalities’ of the Declaration of Independence.”[4]  He warned his students in 1852 that abolitionists were trying to subvert society not according to the word of God but to “socialistic” ideas. By “socialistic” he meant notions that substituted a “man-God for a God-man,” ideas that were “visionary and impractical in a fallen state” in place of the “everlasting word of natural and revealed religion.”[5]

He warned his students in 1852 that abolitionists were trying to subvert society not according to the word of God but to “socialistic” ideas. By “socialistic” he meant notions that substituted a “man-God for a God-man,” ideas that were “visionary and impractical in a fallen state” in place of the “everlasting word of natural and revealed religion.”[5]

But most White northerners in the run-up to the Civil War found ways of squaring the circle between the Declaration and what they saw as the intractable reality of racial inequality. Attacking the proposition that all men are created equal was alarmingly subversive to most people, even when they shared Pettit’s and Lord’s presumption that Black people could never truly be the equals of Whites. Once that ringing claim to equality and liberty was jettisoned, what guarantees would there be that the Union would continue to be the “last, best hope of earth”?[6] One could celebrate the preamble of the Declaration every July Fourth but see the phrase about the equality of man not as a “proposition” to be tested, but, as Jefferson had done, as a “self-evident truth,” Rather than a mission statement for a nation continually striving toward the attainment of an ideal, if the Declaration had merely observed something that already existed, then, by definition, the equality it invoked cannot have meant actual equality of political rights or opportunity, still less equality of condition. It could simply have meant that all were equal in the sight of God, a claim which to many was indeed “self-evident” and which had potentially radical implications, but which also could be accommodated within the reality of a society that, like ours today, is riddled with inequality of status, opportunity, and wealth.

Lincoln’s great Illinois antagonist, the Democratic senator Stephen A. Douglas, revered the Declaration as the touchstone of popular sovereignty with no implications for racial equality at all. The “equality” the slaveholding Jefferson described as “self-evident” was, to Douglas, simply the principle that every White man, whatever his wealth or origins, was the equal of any other. It was the opposite of the aristocratic principle of the Old World.

Lincoln thought this race-bound understanding of the Declaration was impoverished, but, on this point, Douglas probably spoke for the majority in his era. Precisely because abolitionists had begun to invoke the Declaration of Independence, moderate Republicans anxious to build a winning electoral coalition sometimes steered clear of it. At the 1860 Republican Convention in Chicago there was a battle over whether to even include a plank endorsing the Declaration of Independence. The influential newspaper editor Horace Greeley worked hard, unsuccessfully, to scupper the pro-Declaration plank.

Another aspect of Lincoln’s invocation of the Declaration at Gettysburg that was less self-evident to mid-nineteenth-century Americans than we might imagine is the idea that it was a breakpoint in human history. Before the Declaration, no nation had been “so conceived and so dedicated,” in Lincoln’s terms, but it was also commonplace to stress the Revolution’s place in a long tradition of English liberty. This is partly what explains the amazing popularity in nineteenth-century America of the Anglo-Irish philosopher-statesman Edmund Burke, whose strong support of the patriot cause from the House of Commons was grounded in his belief that American freedom grew out of a long tradition of English liberty. From this perspective, the Declaration mattered not because it set out a revolutionary new thesis about human equality based on abstract Enlightenment principles but that it was the latest version of an old idea with deep roots in the Christian past and English radical history. Even patriotic nineteenth-century historians like George Bancroft stressed continuities as well as change. But Lincoln’s formulation stressed the latter, and in wartime it mattered more than ever that the United States be not a truly exceptional nation.

By the time Lincoln spoke at Gettysburg, few people were listening to the outright rejectionism of Reverend Lord or Senator Pettit, and it seemed more natural than might have been the case a few years earlier to cite the Declaration as evidence of the Union’s special purpose. For the mainstream majority of Americans, the Declaration did not have the radical implications that abolitionists hoped, but it gave them something of inestimable value: in a war for national survival, it gave them a sense of purpose. The generation that fought the Civil War genuinely believed that the Union was providentially destined. Whereas other nations simply existed—they were there because they were there—the United States, uniquely, had a mission, and the Declaration of Independence was the mission statement. Nothing else in the founding era could have served the same purpose.

Adam Smith is professor of US politics and political history at University College and director of the Rothermere American Institute at the University of Oxford. He is the author of The Stormy Present: Conservatism and the Problem of Slavery in Northern Politics, 1846–1865 (University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

[1] Abraham Lincoln, Address at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, November 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, ed. Don E. Fehrenbacher (Library of America, 1989), p. 536.

[2] Thomas Jefferson to Henry Lee, May 8, 1825.

[3] Senator John Pettit, in a speech in the Senate in behalf of Stephen A. Douglas’s bill for the organization of two territories, Nebraska and Kansas, February 20, 1854, as quoted in D. W. Wilder, The Annals of Kansas (Topeka, 1886), p. 40.

[4] Nathan Lord, A Letter to J. M. Conrad, Esq., on Slavery (Hanover, NH: The Dartmouth Press, 1860), Library of Congress, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/rbaapc/16500/16500.pdf.

[5] Nathan Lord, The Improvement of the Present State of Things: A Discourse to the Students of Dartmouth College, November 1852 (Hanover, NH: The Dartmouth Press, 1852).

[6] Abraham Lincoln, Annual Message to Congress, December 1, 1862, Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, ed. Don E. Fehrenbacher (Library of America, 1989), p. 415.