"Revered By All": The Declaration of Independence in the Reconstruction Era

by Douglas R. Egerton

Although it was the speech that redefined the conflict and effectively changed the meaning of the Constitution, Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Gettysburg Address is often misunderstood today when it is not simply ignored, at least in American schools. In 1970, as a Phoenix eighth grader, I had to memorize it, but it was just words, learned by rote. My history teacher made no effort to decipher its meaning for us, or to explain why these deceptively simple 271 words challenged the nation to practice what it had long preached. So, in my classes, I ask my students what Lincoln, a most careful wordsmith, meant by his opening line of “Four score and seven years ago.” How many years is that? What document was he then alluding to? And how might the young men who gave their “last full measure of devotion” inspire the nation to rededicate itself “to the proposition that all men are created equal”? Was Lincoln suggesting that the egalitarian promises of 1776 were “unfinished work” for his generation to complete as they pondered how to reconstruct a badly divided nation?[1]

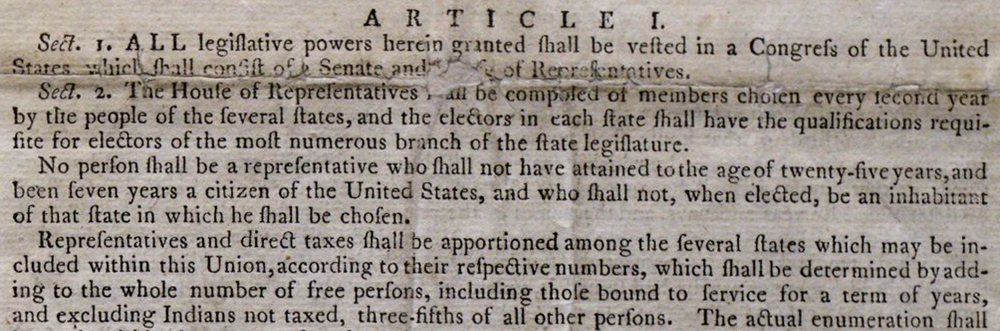

Abolitionists had long argued over whether the Constitution, with its three ambiguous references to “three-fifths of all other persons,” the “importation of such persons,” or “person[s] held to service or labour in one state,” was a profoundly proslavery document, as William Lloyd Garrison believed, or was founded in egalitarian thought and thus was antislavery, as philanthropist Gerrit Smith insisted.[2] Lincoln chose to sidestep that debate. Instead, in speech after speech, Lincoln pointed to the Declaration of Independence as the quintessential statement of American ideals, a document that proclaimed the highest political truths in history, that all people possessed the “unalienable Rights” of “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” Standing, as he was in November 1863, on “a great battle-field” of his nation’s civil war, Lincoln well knew that those promises had been too often unfulfilled, that the man who penned them owned other Americans, and that the Congress who voted to approve them left 893,041 Africans and African Americans enslaved in 1800, just nine years before Lincoln’s birth.

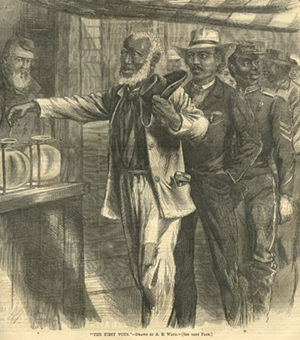

The process of Reconstruction involved amendments to the Constitution and changed both state and federal laws. But on what basis, and where? Most Republican politicians envisioned Reconstruction as a political process involving only the defeated Confederate states. Many Democrats, such as Lincoln’s second vice president, Andrew Johnson, preferred to use the term “restoration,” suggesting the need for only minor adjustments in the law as southern states returned to the Union. Black activists thought otherwise, with Frederick Douglass contending that the entire nation required not merely political, but also social reclamation. Roughly 179,000 Black men had donned blue uniforms in the two years after 1863, but only in New England could Black veterans vote on an equal basis with White men. For many freedmen, the ideals of the Declaration provided an answer. Encouraged by the Freedmen’s Bureau, veterans formed Union League Clubs, political organizations that demanded voting rights and the repeal of discriminatory southern laws. At one 1865 gathering at South Carolina’s St. Helena Island, speakers claimed that “the Declaration of Independence [guaranteed] rights which cannot justly be denied us.” Later that year at a meeting in Charleston, freedmen argued that while the Constitution might regard voting rights as a state prerogative, the spirit of the Declaration decreed otherwise. The Declaration, one delegate swore, provided “the broadest, the deepest, the most comprehensive and truthful definition of human freedom that was ever given to the world.” One White officer at the convention, the Rev. James Hood of North Carolina, marveled at the freedmen’s knowledge of the document. Black Carolinians, he mused, “had read the Declaration until it had become part of their natures.”

By the time Congress passed the Military Reconstruction Act in March 1867, which required former Confederate states to craft new constitutions as the price of readmission, nearly every potential Black voter had joined a local Union League chapter. The groups often convened in Black churches, and typically a Bible and a copy of the Declaration graced the pulpit. As Black veterans and southern freemen—typically ministers and artisans who had been free before the war—helped to draft the new state constitutions, many, as did one Arkansas delegate, pointed to the Declaration as evidence that “all men are created equal.” In the South Carolina legislature, politicians such as Robert Smalls, once an enslaved ship’s pilot, revised antebellum laws using language from the Declaration. Every one of the new southern constitutions guaranteed not merely political rights but also social justice, completing what one Texas freedman called an “equal rights revolution.”

By the time Congress passed the Military Reconstruction Act in March 1867, which required former Confederate states to craft new constitutions as the price of readmission, nearly every potential Black voter had joined a local Union League chapter. The groups often convened in Black churches, and typically a Bible and a copy of the Declaration graced the pulpit. As Black veterans and southern freemen—typically ministers and artisans who had been free before the war—helped to draft the new state constitutions, many, as did one Arkansas delegate, pointed to the Declaration as evidence that “all men are created equal.” In the South Carolina legislature, politicians such as Robert Smalls, once an enslaved ship’s pilot, revised antebellum laws using language from the Declaration. Every one of the new southern constitutions guaranteed not merely political rights but also social justice, completing what one Texas freedman called an “equal rights revolution.”

In a curious, circular fashion, the influence of Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration was quite nearly felt in constitutional revision. Decades before, in 1789, when Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette, was tasked by the French National Assembly with drafting the Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen, he naturally turned for advice to Jefferson, who was then serving as the second minister to France.  Seventy-six years later, Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner, who had spent considerable time abroad, hoped to include one of its phrases in the Thirteenth Amendment: “All persons are equal before the law, so that no person can hold another as a slave.” Michigan senator Jacob Howard, not recognizing Jefferson’s impact on Lafayette’s words, urged Sumner to “go back to good old Anglo-Saxon language.” In the end, the Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by Illinois Republican Lyman Trumbull, instead opted to simply lift the words from the 1787 Northwest Ordinance: “Neither slavery nor servitude, except as a punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States.”

Seventy-six years later, Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner, who had spent considerable time abroad, hoped to include one of its phrases in the Thirteenth Amendment: “All persons are equal before the law, so that no person can hold another as a slave.” Michigan senator Jacob Howard, not recognizing Jefferson’s impact on Lafayette’s words, urged Sumner to “go back to good old Anglo-Saxon language.” In the end, the Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by Illinois Republican Lyman Trumbull, instead opted to simply lift the words from the 1787 Northwest Ordinance: “Neither slavery nor servitude, except as a punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States.”

Three years later, on July 9, 1868, the nation ratified the Fourteenth Amendment. Written to counteract the rising tide of violence in the South and to overturn the Dred Scott decision’s statement that Black Americans could not be citizens of the United States, the lengthy amendment created almost as many problems as it solved. The Republicans’ concern for southern freedmen did not extend to Native Americans, particularly the Cherokee and the Choctaw, whose leadership had sided with the Confederacy. History is filled with ironies for our students to ponder, and here, the same Republican free-soil policies that so outraged southern politicians before the war proved deadly when it came to Native land ownership. Wartime policies like the Homestead Act of 1862, which was designed in part to encourage immigration into the United States, resulted in giving away 160 million western acres to 1.6 million homesteaders. As Lincoln once lectured Congress, Washington needed to reconsider the “possessory rights of the Indians to large and valuable tracts of land” in the West.[3] The same Senator Howard who disagreed with Sumner’s wording for the Thirteenth Amendment but drafted the citizenship clause for the Fourteenth, which automatically made the children of immigrants American citizens, argued that Native peoples were “foreigners, aliens,” who belonged in the same category as “the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers.”[4] Most of his colleagues agreed, and the only reference to Native Americans in the amendment appeared in the section on the apportionment of congressional representatives, “excluding Indians not taxed.” The legal status of Indigenous peoples was not resolved until the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 granted them full citizenship.

The Declaration has nonetheless endured and has inspired revolutionaries around the globe due to the fact that it was never meant to be frozen in time. Speaking at Manhattan’s Cooper Union in early 1860, Lincoln insisted that for all of their flaws, in the Declaration the Founders “meant to set up a standard maxim for free society” that could be “revered by all; constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence.”[5]

Recommended Reading

Egerton, Douglas. The Wars of Reconstruction: The Brief, Violent History of America’s Most Progressive Era. New York: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. New York: Harper and Row, 1988.

Holzer, Harold. Lincoln at Cooper Union: The Speech That Made Abraham Lincoln President. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004.

Morel, Lucas. Lincoln and the American Founding. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2020.

Douglas R. Egerton is a professor of history at Le Moyne College. His books include Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments That Redeemed America (Basic Books, 2016), which was the co-winner of the 2017 Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize, and Heirs of an Honored Name: The Decline of the Adams Family and the Rise of Modern America (Basic Books, 2019), which was a finalist for the George Washington Book Prize.

[1] Abraham Lincoln, Address at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, November 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865, ed. Don E. Fehrenbacher (Library of America, 1989), p. 536.

[2] Final draft of the US Constitution, printed by Dunlap and Claypoole, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, September 17, 1787.

[3] Abraham Lincoln, Annual Message to Congress, December 8, 1863, ALSW, 1859–1865, p. 548.

[4] Senator Jacob Howard, Congressional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2890 (May 30, 1866).

[5] Abraham Lincoln, Speech on the Dred Scott Decision at Springfield, Illinois, June 26, 1857, Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings, 1832–1858, ed. Don E. Fehrenbacher (Library of America, 1989), p. 398.