Abraham Lincoln's "Apple of Gold": The Declaration of Independence

by Harold Holzer

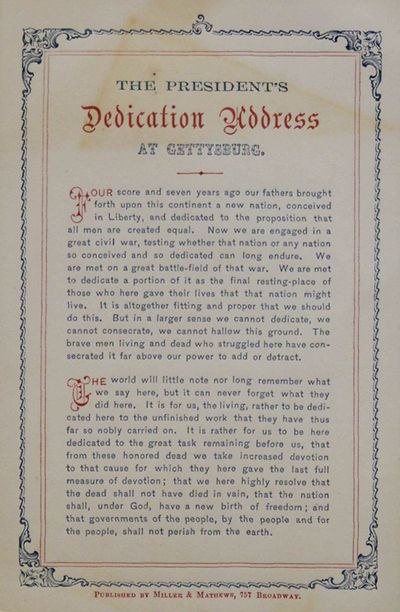

So Abraham Lincoln began the most famous speech of his presidency—arguably the most iconic utterance of the entire Civil War—by implicitly pronouncing the Declaration of Independence America’s preeminent founding document.

The line that opened the Gettysburg Address on November 19, 1863, as Lincoln reminded his listeners, came eighty-seven years after the Declaration. Engaged in a “great civil war” that tested the viability of the Union, Lincoln might just as logically have alluded to 1788, the year the Constitution was ratified. In his inaugural address two years earlier, he had eschewed any mention of the Declaration, instead referring several times to “our national Constitution” while specifically affirming his solemn constitutional oath to “preserve, protect, and defend” the government.[2] For the first fifteen years of his political career, Lincoln had barely mentioned the Declaration of Independence at all.[3] Yet at Gettysburg, he specifically calculated the nation’s birth to July 4, 1776.

For Lincoln, and for many of his nineteenth-century contemporaries, the two founding documents existed in unavoidable contradiction. The sentiments of the Declaration, however, invariably prevailed in Lincoln’s heart and mind over the strictures of the Constitution. To Lincoln, the Declaration approached the sublime, while the Constitution remained imperfect—the product of a compromise that acknowledged slavery in direct contradiction to Jefferson’s promise of unalienable rights. The Constitution demanded adherence, but the Declaration inspired reverence for defining what Lincoln called “our ancient faith”—“the political religion of the nation.”[4]

When his lifelong political rival, Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, engineered passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, Lincoln held the new law’s principal innovation, “popular sovereignty,” to be a defilement of that faith. Indifference to the spread of slavery, Lincoln insisted, made a mockery of Jefferson’s binding promise of equality and opportunity. Popular sovereignty gave White settlers the right to vote on legalizing slavery in the western territories, and as Lincoln pointed out, “there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another.”[5]

“Let us readopt the Declaration of Independence,” he instead urged at Peoria that October, “and with it, the practices, and policy, which harmonize with it. Let north and south—let all Americans—let all lovers of liberty everywhere—join in the great and good work. If we do this, we shall not only have saved the Union, but we shall have so saved it, as to make, and to keep it, forever worthy of the saving.”[6]

Lincoln intensified his references to the document in 1858, the year he challenged Douglas’s quest for a third term. “You may not only defeat me for the Senate, but you may take me and put me to death,” he dramatically told voters in a campaign speech that August, “But do not destroy that immortal emblem of Humanity—the Declaration of American Independence.”[7] A pro-Republican journalist on the scene hailed “Mr. Lincoln’s noble and impressive apostrophe to the Declaration,” calling it “one of the finest efforts of public speaking I ever listened to.”[8]

Throughout the widely attended, extensively reported Lincoln-Douglas debates that summer and fall, the candidates argued over whether the Declaration applied to Blacks as well as Whites. Douglas held that its signers meant it to apply only to Americans of European descent. Risking charges that he favored racial equality—a position few mainstream political candidates were willing to embrace in 1858—Lincoln unwaveringly maintained that the document offered its guarantees to all. Between debates, he charged the Douglas Democrats with “petty sneers” against the Declaration, attacks once unimaginable but now “fast bringing that sacred instrument into contempt.” Adding a sneer of his own, Lincoln taunted, “Are Jeffersonian Democrats willing to have the gem taken from the magna charta [sic] of human liberty in this shameful way?”[9]

With Lincoln’s encouragement, the Declaration was fast becoming the exclusive political property of the Republican Party. As Lewis E. Lehrman has pointed out, “To hijack Jefferson from the Democrats was a sincere and shrewd maneuver to reawaken national reverence for the Declaration of Independence and the antislavery sentiments Jefferson had expressed in that document.” The Declaration thereafter “became the bedrock upon which Lincoln . . . built his philosophical and political reasoning.”[10]

Lincoln lost the Senate contest, but not his adherence to the Declaration, convinced that most Americans similarly embraced its guarantees.

His election to the presidency two years later, and the onset of secession within weeks, forced Lincoln into his most tortured inner conflict over the founding documents. To keep the Union whole, he cited his constitutionally guaranteed right to assume control of the government and keep southern states in the Union. However, as the Secession Winter engulfed him in a crisis he had no power to address until inauguration day in March, Lincoln continued to hope (over-optimistically) that he could harmonize the Constitution and the Declaration as twin guideposts for a united future. For a time, he kept these sentiments to himself, making no new public statements between his election and his departure for Washington.

However, in a fragment crafted before leaving his hometown, he imagined that the nation might yet be saved precisely because it had been inspirited by a declaration of principles and then protected by a constitution of laws. Without the aspirational expressions in the Declaration, he opined, “we could not, I think, have secured our free government, and consequent prosperity.” Echoing the Book of Proverbs—further proof that Lincoln considered the Declaration equivalent to American scripture—he described Jefferson’s gem as “the word, ‘fitly spoken’ which has proved an ‘apple of gold’ to us.” The “Union, and the Constitution,” he perpetuated the biblical metaphor, “are the picture of silver subsequently framed around it. . . . The picture was made for the apple—not the apple for the picture. So let us act, that neither picture, or apple shall ever be blurred, or bruised or broken.”[11] Historian Ronald C. White believes Lincoln likely kept this note “for his eyes only” because he realized the concept of equal rights for all—implicitly including Blacks—remained “too radical for dissemination at this moment.”[12]

“I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence,” he proudly admitted to “great cheering” from the audience filling the shrine where the document had been signed. “It was not the mere matter of the separation of the colonies from the mother land; but something in that Declaration giving liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but hope to the world for all future time. It was that which gave promise that in due time the weights should be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that all should have an equal chance. . . . Now, my friends, can this country be saved upon this basis? If it can, I will consider myself one of the happiest men in the world if I can help to save it.”[13]

The Civil War brought no happiness to Abraham Lincoln, but no pause in his resolve to save the Union—along with its founding promise—despite the war’s astronomical cost in life and treasure. To the end, as Walt Whitman stated, Lincoln remained “Dear to Democracy, to the very last,” while democracy, as articulated in the Declaration, remained dear to Lincoln (even as he skirted the constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech and the press).[14] The “new birth of freedom” that he promised at Gettysburg mid-war unquestionably traced its origins to one primary parent: the document issued in 1776. The Union would not perish from the earth, Lincoln suggested, if it could be saved according to its founding guarantees.

With uncanny prescience, he even warned about what might happen if its principles were forgotten or forsaken in the future.

“Its authors meant it to be, thank God . . . a stumbling block to those who in after times might seek to turn a free people back into the hateful paths of despotism,” Lincoln declared. “They knew the proneness of prosperity to breed tyrants, and they meant when such should re-appear in this fair land and commence their vocation, they should find left for them at least one hard nut to crack.”

“And now I appeal to all,” he concluded, “are you really willing that the Declaration should be thus frittered away?—thus left no more at most, than an interesting memorial of the dead past? . . . left without the germ or even the suggestion of the individual rights of man in it?”[15]

Lincoln was not willing to fritter away the Declaration—or abandon its guarantees of individual rights—and clearly hoped future generations would feel the same way.

Harold Holzer, who leads the Presidents vs. the Press course in the Gettysburg College–Gilder Lehrman MA in American History, received the 2015 Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize for Lincoln and the Power of the Press: The War for Public Opinion (Simon & Schuster, 2014). He is the Jonathan F. Fanton Director of the Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College.

[1] Final text of the Gettysburg Address, delivered on November 19, 1863, in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 8 vols., hereafter referred to as CWL (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953–1955), 7: 22–23.

[2] First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861, CWL 4:265 (“our national Constitution”); 271 (“solemn oath”).

[3] Historian Allen C. Guelzo calculates that Lincoln cited the Declaration only twice between 1838 and 1854—in his 1838 Lyceum Address and his 1852 eulogy for Henry Clay. See Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1999), 193.

[4] Speech at Peoria, Illinois, October 16, 1864, CWL 2:266. At both Cooper Union in February 1860 and at his first inaugural in March 1861, Lincoln reminded southerners they need not fear him, pointing out that he lacked constitutional authority to act on his moral opposition to slavery. “Civil Religion” from Lincoln’s Young Men’s Lyceum Address, Springfield, Illinois, January 27, 1838, CWL 1:112.

[5] Peoria Address, CWL 2:266.

[6] Peoria Address, CWL 2:255, 276.

[7] Speech at Lewistown, Illinois, August 17, 1858, CWL 2:547.

[8] Chicago Press & Tribune, August 21, 1858.

[9] Speech at Carlinville, Illinois, August 31, 1858, CWL 3:80.

[10] Lewis E. Lehrman, Lincoln at Peoria: The Turning Point—Getting Right with the Declaration of Independence (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2008), 107–108.

[11] Fragment on the Constitution and the Union, ca. January 1861, CWL 4:169. Lincoln may also have kept these thoughts to himself because they likely originated with his one-time colleague, Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia, whom Lincoln briefly considered for a Cabinet post as a gesture of sectional reconciliation. Lincoln ultimately made no offer to the former congressman, and Stephens went on to serve as vice president of the Confederacy. For the text of his letter to Lincoln, December 30, 1860 (“A word ‘fitly spoken’ by you now, would indeed be ‘like apples of gold, in pictures of silver’”), see Stephens, A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States: Its Causes, Character, Conduct and Results, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: National Publishing Co., 1868–1870), 2:270.

[12] Ronald C. White, Lincoln in Private: What His Most Personal Reflections Tell Us about Our Greatest President (New York: Random House, 2021), 131–132.

[13] Speech at Independence Hall, Philadelphia, February 22, 1861, CWL 4:240.

[14] Walt Whitman essay in Allen Thorndike Rice, ed., Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln by Distinguished Men of His Time (New York: North American Publishing Co., 1886), 475.

[15] Speech at Springfield, Illinois, June 26, 1857, CWL 2:406–407.