"All Should Have an Equal Chance": Abraham Lincoln and the Declaration of Independence

by Jonathan W. White

![Abraham Lincoln [cabinet card], photographed by C. S. German, Springfield, Illinois, January 1861. (The Gilder Lehrman Institute, GLC05111.01.1328)](/sites/default/files/2023-07/GLC05111.01.1328p1_300x400px.jpg) In many ways, the Gettysburg Address reflects the culmination of Abraham Lincoln’s lifelong admiration for the principles of the Declaration of Independence. As a young man in 1838, Lincoln responded to the wave of mob violence sweeping through the nation by calling on Americans to “swear by the blood of the Revolution, never to violate in the least particular, the laws of the country; and never to tolerate their violation by others.” Alluding to the words of the Declaration itself, Lincoln intoned, “As the patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence, so to the support of the Constitution and Laws, let every American pledge his life, his property, and his sacred honor.”[1]

In many ways, the Gettysburg Address reflects the culmination of Abraham Lincoln’s lifelong admiration for the principles of the Declaration of Independence. As a young man in 1838, Lincoln responded to the wave of mob violence sweeping through the nation by calling on Americans to “swear by the blood of the Revolution, never to violate in the least particular, the laws of the country; and never to tolerate their violation by others.” Alluding to the words of the Declaration itself, Lincoln intoned, “As the patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence, so to the support of the Constitution and Laws, let every American pledge his life, his property, and his sacred honor.”[1]

Lincoln believed that each successive generation of Americans must remember and revere the sacrifices of the generations that came before them. If Americans turned their backs on the nation’s founding principles of liberty, equality, and government by consent, they risked losing all that they had “inherit[ed]” from “our fathers.” He warned: “If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.”[2]

While Lincoln did not advocate for full political or social equality for African Americans, he fought against political leaders, like Chief Justice Roger B. Taney and Sen. Stephen A. Douglas, who claimed that the Declaration did not include Black men and women within its majestic language. In response to the Dred Scott decision (1857), Lincoln argued that “the Declaration contemplated the progressive improvement in the condition of all men everywhere.” The Founders knew that they could not attain perfect equality in 1776, but they enshrined certain words in the Declaration “for future use” and to augment “the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere.”[3]

In a speech delivered at the Illinois state capitol in Springfield in June 1857, Lincoln urged his audience to recognize that African Americans deserved certain rights that were being denied them. Using a hypothetical enslaved woman as an example, he said, “In her natural right to eat the bread she earns with her own hands without asking leave of any one else, she is my equal, and the equal of all others.” This was a remarkable statement for a midwestern politician to make in the 1850s, for he was telling a White, male audience that “all people of all colors” were included within the sacred words of the Declaration.[4]

At the conclusion of his speech, Lincoln addressed the situation of two specific African American young women—Dred Scott’s daughters, Lizzie and Eliza. Lincoln said: “We desired the court to have held that they were citizens so far at least as to entitle them to a hearing as to whether they were free or not; and then, also, that they were in fact and in law really free.” Then, alluding to the sexual assault of enslaved women that was all too prevalent on southern plantations, he continued, “Could we have had our way, the chances of these black girls, ever mixing their blood with that of white people, would have been diminished at least to the extent that it could not have been without their consent.” By using the words “citizens” and “consent” Lincoln was implicitly suggesting that Black women were “human enough to have a hearing” and to be included within the principles of the Declaration—that they, too, deserved liberty, equality, and perhaps even government by consent.[5]

At the conclusion of his speech, Lincoln addressed the situation of two specific African American young women—Dred Scott’s daughters, Lizzie and Eliza. Lincoln said: “We desired the court to have held that they were citizens so far at least as to entitle them to a hearing as to whether they were free or not; and then, also, that they were in fact and in law really free.” Then, alluding to the sexual assault of enslaved women that was all too prevalent on southern plantations, he continued, “Could we have had our way, the chances of these black girls, ever mixing their blood with that of white people, would have been diminished at least to the extent that it could not have been without their consent.” By using the words “citizens” and “consent” Lincoln was implicitly suggesting that Black women were “human enough to have a hearing” and to be included within the principles of the Declaration—that they, too, deserved liberty, equality, and perhaps even government by consent.[5]

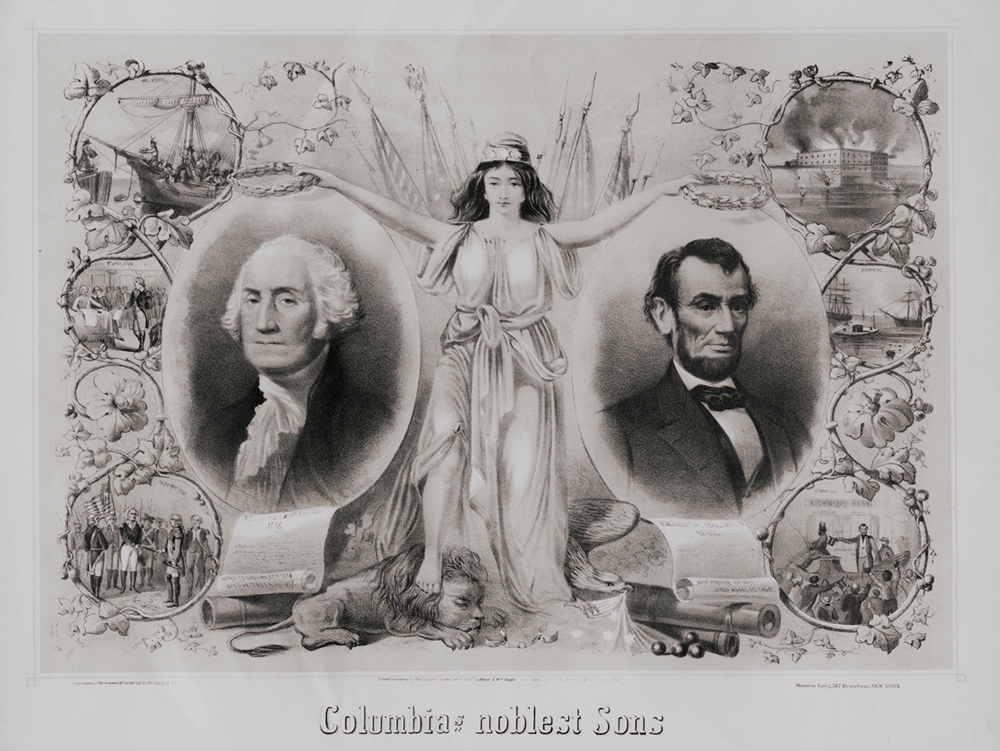

As president-elect in 1861, Lincoln gave a brief, impromptu speech at Independence Hall on George Washington’s birthday, February 22. Filled with “deep emotion” while standing in that historic place, Lincoln told the crowd “that all the political sentiments I entertain have been drawn, so far as I have been able to draw them, from the sentiments which originated, and were given to the world from this hall. . . . I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.” Since his boyhood, Lincoln had been fascinated by the stories of the American Revolution. He had “often pondered over the dangers which were incurred by the men who assembled here and adopted that Declaration of Independence,” and thought of “the soldiers of the army, who achieved that Independence.” The “great principle or idea” that motivated them was “the sentiment embodied in that Declaration of Independence” which gave “liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but hope to the world for all future time. It was that which gave promise that in due time the weights should be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that all should have an equal chance.” Speaking extemporaneously, Lincoln added, “I would rather be assassinated on this spot than to surrender” that great principle.[6]

Lincoln continued to urge Americans to remember and revere the sacrifices of the founding generation. In his inaugural address on March 4, 1861, he appealed to the North and South’s shared revolutionary heritage when he urged White southerners not to go to war: “The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” But this appeal went unheeded. And the war came.[7]

Lincoln continued to urge Americans to remember and revere the sacrifices of the founding generation. In his inaugural address on March 4, 1861, he appealed to the North and South’s shared revolutionary heritage when he urged White southerners not to go to war: “The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” But this appeal went unheeded. And the war came.[7]

For the first year of the Civil War, Lincoln pledged not to touch slavery where it existed because, he said, he had no constitutional authority to do so. Nevertheless, he attacked slavery in ways that the Constitution permitted, such as working to destroy the transatlantic slave trade, abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia, and offering financial compensation to the Border States to incentivize them to abolish slavery (this latter plan bore no fruit). Finally, in the summer of 1862, Lincoln decided that abolishing slavery in the Confederacy could be justified as a “military necessity” because it would help win the war. He issued his final Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, calling that document “the central act of my administration, and the greatest event of the nineteenth century.”[8] He added, “If my name ever goes into history it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.”[9] By presidential edict, the commander-in-chief inextricably linked Black freedom with restoration of the Union.

When Lincoln went to Gettysburg in November 1863 to consecrate a national cemetery, he sought to help his fellow citizens see that the principles of emancipation were congruent with the founding principles of the nation. He developed this complex argument in a speech that lasted a mere two minutes.

He opened: “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”[10] This first paragraph pointed his listeners to the founding of the nation. It was founded, he said, in 1776, when the Continental Congress placed ideas of liberty and equality into the Declaration—not in 1787, when the Constitution was written. The United States was, therefore, established on ideas, not structures of government.

While the Declaration stated that the principle of equality was a “self-evident truth,” Lincoln spoke of it as a “proposition”—meaning something that had to be proved. Through the blood and sacrifice of the Civil War, the American people were proving that, over time, they could live up to the great “truth” of human equality. Lincoln continued: “Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.” On this battlefield, Lincoln called on Americans to remember and commemorate the sacrifices of “those who here gave their lives that that nation might live.” From their “last full measure of devotion” the United States “shall have a new birth of freedom” so “that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”[11]

But who were “the people” Lincoln was referring to in these immortal lines? The “new birth of freedom” would require that they be Black as well as White.

In this two-minute speech, Lincoln summed up the principles that had animated his life—from his childhood reading about Revolutionary heroes, to his 1838 Lyceum Address in which he called on Americans to remember and cherish the principles of the Revolution, to his response to the Dred Scott decision in 1857, to his inaugural journey in 1861. Lincoln’s leadership during the Civil War was motivated by the belief that the ideas embodied in the Declaration of Independence applied “to all people of all colors everywhere.” It is little wonder, then, that when he entered Richmond in April 1865, just a few short days before his assassination, he told a group of recently freed slaves, “You are as free as I am, having the same rights of liberty, life and the pursuit of happiness.”[12]

Jonathan W. White is a professor of American studies at Christopher Newport University. He is the author of AHouse Built by Slaves: African American Visitors to the Lincoln White House(Rowman & Littlefield, 2022), which won the Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize, and Shipwrecked: A True Civil War Story of Mutinies, Jailbreaks, Blockade-Running, and the Slave Trade (Rowman & Littlefield, forthcoming August 2023).

[1] Abraham Lincoln, Address to the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois, January 27, 1838, Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings, 1832–1858 (ALSW, 1832–1858), ed. Don E. Fehrenbacher (New York: Library of America, 1989), p. 32.

[2] Lincoln, Address to the Young Men’s Lyceum, ALSW, 1832–1858, pp. 28, 29.

[3] Abraham Lincoln, Speech on the Dred Scott Decision at Springfield, Illinois, June 26, 1857, ALSW, 1832–1858, pp. 400, 399, 398.

[4] Lincoln, Speech on the Dred Scott Decision, ALSW, 1832–1858, pp. 397–398.

[5] Lincoln, Speech on the Dred Scott Decision, ALSW, 1832–1858, p. 401.

[6] Abraham Lincoln, Speech at Independence Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, February 22, 1861, Abraham Lincoln: Speeches and Writings, 1859–1865 (ALSW, 1859–1865), ed. Don E. Fehrenbacher (New York: Library of America, 1989), p. 213.

[7] Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861, ALSW, 1859–1865, p. 224.

[8] Abraham Lincoln to F. B. Carpenter, February 1865, as quoted in The Lincoln Year Book, ed. J. T. Hobson (Dayton, Ohio: United Brethren Publishing House, 1912), p. 10.

[9] Abraham Lincoln to William H. Seward, January 1, 1863, as quoted in Gilson Willets, Inside History of the White House (New York: The Christian Herald, 1908), p. 208.

[10] Abraham Lincoln, Address at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, November 19, 1863, ALSW, 1859–1865, p. 536.

[11] Lincoln, Address at Gettysburg, ALSW, 1859–1865, p. 536.

[12] Abraham Lincoln, Address of Abraham Lincoln to the freed African Americans in Richmond, Virginia, April 4, 1865, as quoted in A. H. Newton, Out of the Briars: An Autobiography and Sketch of the Twenty-ninth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers (Philadelphia: The A. M. E. Book Concern, 1910), p. 67.