The Will to Be Free: On the Declaration of Independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam

by Thuy Vo Dang

In his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., wrote that “freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.” [1] His letter addressed his fellow clergymen amidst the turmoil of the American civil rights era and called for direct action to emancipate Black people from the injustices of segregation and racism. Yet the call resounds widely with struggles for freedom from the shackles of colonial rule all over the world. Having endured centuries of oppression by foreigners, Vietnamese people have demanded freedom throughout history; they have fought and died for an autonomous Vietnam. Summarizing this struggle, Vietnamese musician Trịnh Công Sơn (1939–2001) wrote these popular lyrics about his beloved country:

In his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., wrote that “freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.” [1] His letter addressed his fellow clergymen amidst the turmoil of the American civil rights era and called for direct action to emancipate Black people from the injustices of segregation and racism. Yet the call resounds widely with struggles for freedom from the shackles of colonial rule all over the world. Having endured centuries of oppression by foreigners, Vietnamese people have demanded freedom throughout history; they have fought and died for an autonomous Vietnam. Summarizing this struggle, Vietnamese musician Trịnh Công Sơn (1939–2001) wrote these popular lyrics about his beloved country:

Một ngàn năm nô lệ giặc Tầu [A thousand years enslaved by Chinese invaders]

Một trăm năm đô hộ giặc Tây [A hundred years dominated by Western invaders]

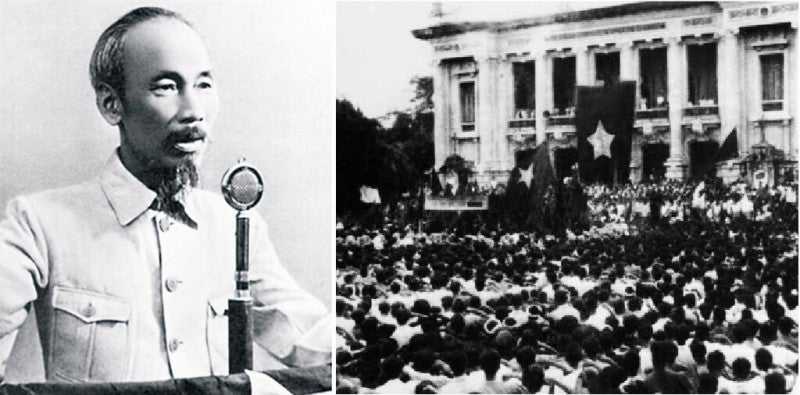

From the 1965 song titled “Gia tài của mẹ” [Mother’s Legacy], these few lyrics condense Vietnam’s legacy of colonialism and serve as context for the importance of September 2, 1945. On this day, just hours after Japan surrendered in World War II, political leader Hồ Chí Minh formally declared Vietnam’s independence from France. Standing in the symbolic Ba Đình Square in Hanoi, Hồ Chí Minh paraphrased the American Declaration of Independence (1776) and referenced France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789). The Declaration of Independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam asserts, “All men are created equal. They are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, among them are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” [2]

The significance of this proclamation of independence for Vietnam should be placed in context of a fierce desire for self-determination by the Vietnamese, who collectively endured thousands of years of Chinese domination and eighty years of colonization by France followed by a five-year period of Japanese occupation during World War II. This history of colonization was met with strong resistance, as exemplified by Vietnam’s national heroes who led revolutions that defeated the Chinese, such as the Trưng Sisters in AD 40, Lý Nam Đế in AD 544, and Lê Lợi in 1483. Hồ Chí Minh’s decision to read his proclamation at Ba Đình Square is symbolic because this location is named after the Ba Đình Uprising, part of an anti-French movement in 1886–1887.

The seeds of European expansion into Vietnam were planted as early as the 1500s, with the arrival of missionaries who relayed information about the exploitable resources of the country. On the surface, these missionaries believed they were spreading their brand of civilization, or mission civilisatrice, as the French called their imperial projects. In 1857, France invaded Vietnam to expand its control in Asia in competition with other Western powers. The main motivation was to exploit natural resources including rice, coal, rare minerals, and rubber. France occupied not only Vietnam, but also two other countries located in Southeast Asia—Cambodia and Laos—and renamed that area the Indochina Union. While “Indochina” and “Indochinese” are historical terms used to describe the territories and people of Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam under French rule, many Vietnamese scorn the terms as challenges to their independent identities, which should be studied beyond the stamps of foreign control. Just as the influence of Chinese culture on Vietnam is evident throughout the years, the era of French colonialism in “Indochina” has resulted in an integration of France’s religion, language, architecture, arts, and cuisine by the Vietnamese people. Some of the most well-recognized influences of French colonialism are cà phê sữa đá (Vietnamese coffee with condensed milk) and the baguette.

World War II opened the floodgates for yet another foreign aggressor. After France fell to Germany in 1940, Japan gained control of Vietnam. However, Japan allowed French officials and troops to manage the country. This wartime occupation made Vietnam the most important World War II staging area for Japanese military operations in all of Southeast Asia. By this time, Hồ Chí Minh had been building up support in the Soviet Union and China for his revolutionary cause. He had traveled and studied widely throughout Europe, Asia, and the United States for thirty years, adopting and organizing around Marxist-Leninist political thought. Furthermore, he was a member of the French communist party and had revolutionary networks throughout the Western world. Japan and France’s uneasy partnership in Vietnam presented a window of opportunity for revolutionary leaders to liberate the country from foreign control. Thus, Hồ Chí Minh came back to Vietnam in 1941 and established the Việt Minh, Vietnam’s communist independence movement aimed at removing the Japanese and French.

In March 1945, for fear that the French would turn against them in Southeast Asia, Japan ousted France from Vietnam and propped up the Nguyễn Dynasty’s Bảo Đại as a figurehead ruler. From his throne in the Imperial City of Huế, Bảo Đại was the last emperor to “rule” Vietnam, but in reality he had very little power. Additionally, in this year of political change, the northern part of the country was suffering from a severe famine caused and prolonged by a combination of factors: typhoons, Japanese occupation, mismanagement by the French administration, and US attacks on the country’s transportation system. These conditions laid bare the exploitation and suffering of Vietnamese people under multiple foreign colonial powers.

In September 1945, to make the case for why Vietnam should be independent of foreign rule, Hồ Chí Minh pointed out the hypocrisy of France in his speech:

For more than eighty years, the French imperialists, abusing the standard of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity, have violated our Fatherland and oppressed our fellow-citizens. They have acted contrary to the ideals of humanity and justice.

The “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity” propounded by the French clearly did not extend to those they exploited in Southeast Asia for their own political and economic gains, even as France called Vietnam its “protectorate.” Thus, Vietnamese made demands to be free from oppression, and their declaration of independence allowed them to point to the contradictions of western colonial aggression. Along with this formal declaration, the Việt Minh led an uprising and seized Hanoi. Emperor Bảo Đại abdicated his throne and pledged to support the newly formed Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

From this momentous proclamation of independence, it would be another thirty years before Vietnam was united by one autonomous government under the banner of Vietnamese communism. The decades after 1945 became known as the American era in Vietnam. In America, it is viewed as a politically divisive period when civil rights, women’s rights, anti-war movements, and third-world liberation struggles shaped American political and cultural identities. During this time Vietnam, a nation that had survived centuries of foreign aggression, became entangled in a prolonged and bloody war—a war sometimes described as a civil war between North (communist) and South (noncommunist), and other times described as a revolution waged by nationalists to remove colonizers (in this instance, Americans) from the country yet again. Anti-colonial resistance is an important thread that runs through the fabric of Vietnamese myth, history, and cultural productions. This indomitable spirit of resistance has been a source of pride for Vietnamese inside the country and those scattered throughout the world. Despite political differences between communists and anticommunists among the Vietnamese people today, most will agree that Vietnam’s resiliency as a nation is rooted in the people’s will to be free.

Thuy Vo Dang, Ph.D., is the curator of the Southeast Asian Archive and research librarian for Asian American Studies at the University of California, Irvine. She is the co-author of Vietnamese in Orange County (Arcadia Publishing, 2015) and a member of the board of directors of the Vietnamese American Arts & Letters Association.

[1] Martin Luther King, Jr., “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” April 16, 1963.

[2] Hồ Chí Minh, Selected Works, vol. 3 (Hanoi: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1960–62), 17–21.