Insurgent India: Purna Swaraj as Self-Determination

by Ishita Banerjee-Dube

“At the stroke of midnight, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.” These are the famous words of Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India, that began his resonant “Tryst with Destiny” speech of August 14, 1947, on the eve of India’s independence. It was almost two decades before, at its annual session, that the Indian National Congress had made Purna Swaraj, complete independence, the goal of India’s nationalist struggle. The resolution surpassed the prior demand merely for Dominion Status within the British Commonwealth. The decision—introduced, debated, and adopted on December 19, 1929—was celebrated with an event at midnight on December 31. Signifying the end of an era and the beginning of a new one, the Indian flag was unfurled in Lahore (now in Pakistan), to the singing of “Bande mataram” (“Hail you, o Mother”) and the cries of inquilab zindabad, long live the revolution.[1] The blend of revolution and adoration of the motherland with an acceptance of the nonviolent methods of Indian nationalism introduced and developed by the Mahatma (great soul), Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869–1948), made this ceremonial hoisting of the flag and the declaration of full independence singular and alluring.

“At the stroke of midnight, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.” These are the famous words of Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India, that began his resonant “Tryst with Destiny” speech of August 14, 1947, on the eve of India’s independence. It was almost two decades before, at its annual session, that the Indian National Congress had made Purna Swaraj, complete independence, the goal of India’s nationalist struggle. The resolution surpassed the prior demand merely for Dominion Status within the British Commonwealth. The decision—introduced, debated, and adopted on December 19, 1929—was celebrated with an event at midnight on December 31. Signifying the end of an era and the beginning of a new one, the Indian flag was unfurled in Lahore (now in Pakistan), to the singing of “Bande mataram” (“Hail you, o Mother”) and the cries of inquilab zindabad, long live the revolution.[1] The blend of revolution and adoration of the motherland with an acceptance of the nonviolent methods of Indian nationalism introduced and developed by the Mahatma (great soul), Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869–1948), made this ceremonial hoisting of the flag and the declaration of full independence singular and alluring.

The text that the Indian National Congress produced to formally encode its resolution was made public on January 26, 1930. It stated

The British government in India has not only deprived the Indian people of their freedom but has based itself on the exploitation of the masses, and has ruined India economically, politically, culturally, and spiritually. We believe, therefore, that India must sever the British connection and attain Purna Swara or complete independence.[2]

The resolution—a mere 750-word document, without any legal-constitutional grounding—was presented to the world as a “pledge” of the Indian people. It affirmed that as Indians, “we hold it to be a sin before man and God to submit any longer to a rule that has caused this four-fold disaster to the country.” Here, the most effective way of gaining freedom was not through violence. “We will therefore prepare ourselves by withdrawing, so far as we can, all voluntary association from the British Government, and will prepare for civil disobedience, including nonpayment of taxes.”[3]

The insistence on nonviolence and civil disobedience—alongside the use of terms such as “pledge,” “sin,” and “four-fold disaster”—reveal the strong imprint of Gandhi.[4] Interestingly, Gandhi at this stage was not in favor of complete independence. His idea of swa-raj (self-rule), elaborated in his text Hind Swaraj (1909), was different from that of mere political independence. It envisaged a transformation of society from the grassroots, with each Indian leading his/her own swa, proper life on the path of truth and morality.

In the years immediately preceding 1929, leaders of the Congress and other political parties, unhappy with the institutional reforms implemented by the colonial government and dismayed at its appointment of an all-White commission to recommend further reforms, had taken the initiative of drafting a constitution for India. This draft constitution had proposed self-rule for India with “Dominion Status,” a status that had been granted to White dominions of the British Empire in 1926.

The pledge, with its intriguing mix of religious-political idiom, remains significant as a document that marks a radical departure in Indian nationalism’s engagement with British colonial rule. Instead of being supplicants for institutional reforms as an act of “charity” by the colonizing state, Indians now demanded independence on grounds of justice.[5] The framers of the constitution of independent India acknowledged and granted further symbolic significance to the document by deciding to formally implement the constitution of the “sovereign, socialist, democratic republic” of India on January 26, 1950. January 26 continues to be celebrated as India’s Republic Day.

Interestingly, January 26 is also the National Day of Australia, commemorating the landing of the first European fleet in 1788 and the beginning of European settlement that eventually resulted in the attainment of nationhood. For the original inhabitants, the Indigenous Australians, on the other hand, January 26 represents the beginning of the destruction of a way of life and of the culture of a people. This serves as a strong reminder of the multiple connotations and diverse significance of national days, their discrete construction, and their celebration.

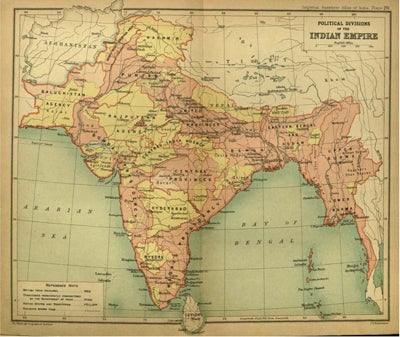

The English—like the Portuguese, Dutch, and French before them—had come to India as traders and merchants. The lure of Indian spices and textiles combined with the attraction of the thriving Indian Ocean trade had drawn Europeans to India from very early times. The English East India Company, a joint-stock company of London merchants, set up by a royal charter in 1600 to trade in the East, had been granted monopoly over all trade between England and Asia. Through a long and convoluted process, this trading company transformed itself into a ruling power by 1757 with its conquest of Bengal. This colonial dominance continued until the great revolt of 1857, when it was replaced by the imperial power under the aegis of the queen and the British Parliament. The 1858 “Proclamation” of Queen Victoria brought India under direct British rule, transformed Indians into subjects of the British Crown, and promised institutional reforms that were to train, teach, and enable Indians to arrive at “self-rule” in a distant future. The declaration of Purna Swaraj articulated Indian political aspirations for self-determination where self-rule symbolized a repudiation of and severance of ties with the colonial power.

The assertion of complete independence that entailed the right to determine who to be ruled by was not a unique decision of Indian nationalists. It was in tune with wider anti-colonial struggles in large parts of Asia and Africa encouraged by international developments, particularly in Europe. The principle of self-determination of nations, attributed to the American president Woodrow Wilson, and to Lenin and Stalin of the Soviet Union, gained prominence in the period between the two world wars, and became a vital force after World War II, when it was given legal status by the United Nations Charter. Tied to an acknowledgment of nation-states as sovereign territorial units with the right of self-rule, the principle was vigorously applied to Europe after World War I, but not to the European colonies in Asia and Africa. At the same time, its presence strengthened an international anti-colonial upheaval where nationalists of colonized countries sought new allies, languages, and methods in their quest to challenge imperialism and launched a moral demand for self-rule.[6]

Even as such calls became difficult for imperial authorities to ignore, especially from the late 1940s, it was also the case that the formations of new nations could afford Western powers novel spheres of influence. Asia and Africa witnessed a wave of decolonization and the founding of sovereign nation-states from the late 1940s to the early 1980s. Post-independence, however, India and other nation-states have emphasized the virtue of national sovereignty and territorial integrity to quash aspirations of self-determination of peoples within their territories.[7] All of this behooves us to reconsider the contested significance and sentiments of the nation and nation-states.

Ishita Banerjee-Dube is professor of history at the Centre for Asian and African Studies, El Colegio de México in Mexico City. She is the author of A History of Modern India (Cambridge University Press, 2015) and Religion, Law and Power: Tales of Time in Eastern India, 1860–2000 (Anthem Press, 2007).

[1] Sumit Sarkar, Modern India: 1885–1947 (New Delhi: Macmillan, 1983), 284.

[2] Constitution of India, Declaration of Purna Swaraj (Indian National Congress, 1930). Accessed on September 16, 2021.

[3] Constitution of India, Declaration of Purna Swaraj (Indian National Congress, 1930).

[4] Ishita Banerjee-Dube, A History of Modern India (Cambridge, New Delhi, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 329.

[5] Mithi Mukherjee, India in the Shadows of Empire: A Legal and Political History, 1774–1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 214.

[6] Erez Manela, The Wilsonian Moment: Self Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), ix.

[7] Srinivas Burra, “Where Does India Stand on the Right to Self-Determination?” Economic and Political Weekly, January 14, 2017, 21.