The Declaration of Independence and the Origins of Modern Self-Determination

by David Armitage

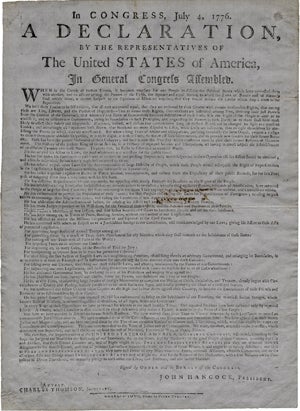

Ask any American what the opening lines of the US Declaration of Independence of 1776 are and chances are they might reply, “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” and then go on to recite its inspiring statements on human equality and the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Yet, important as these words are, they are not the first in the Declaration, nor are they even its leading thought. That distinction goes to what, with hindsight, we can now recognize as a historically precocious statement of self-determination:

Ask any American what the opening lines of the US Declaration of Independence of 1776 are and chances are they might reply, “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” and then go on to recite its inspiring statements on human equality and the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Yet, important as these words are, they are not the first in the Declaration, nor are they even its leading thought. That distinction goes to what, with hindsight, we can now recognize as a historically precocious statement of self-determination:

When in the Course of human Events, it becomes necessary for one People to dissolve the Political Bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent Respect to the Opinions of Mankind requires, that they should declare the Causes which impel them to the Separation.

The key ideas here are the dissolution of existing ties, the assumption of a new international status, and the necessity of separation: that is, not the equality and rights of individuals, but the equality and rights of peoples and of their arrangement into independent political units, or states.

Americans are now so accustomed to seeing the Declaration as a foundational document of nationhood, it is difficult to imagine just how novel and radical such statements were in 1776. After all, this was a period when the large-scale political communities familiar to most people, in most parts of the world, were not nation-states but multinational empires. The notion that “one People” might find it “necessary” to dissolve its links with a larger polity—that is, that it might legitimately attempt to secede from an empire or a composite state—was almost entirely unprecedented and barely accepted at the time of the American Revolution. To be sure, there was a handful of instances in European history that the rebellious colonists could hark back to, most notably the successful secession in the early seventeenth century of the Netherlands from the Spanish Monarchy to form the Dutch Republic (a new political community sometimes known, revealingly, as a set of “united states”). But, by and large, existing empires and states fiercely resisted movements toward secession and did all they could to suppress them—as, of course, Britain tried to do in the course of the American War of Independence. At the time of the Declaration, self-determination was little promoted, hardly theorized, and rarely if ever achieved.

If we fast forward to our own time, we might say that some aspects of that consensus have not greatly changed. There is still no internationally acknowledged right to self-determination, or what international lawyers would call a “peremptory norm” in its favor. Secession is generally only legitimate when states collapse for other reasons—think of the implosion of the former Yugoslavia during the Balkan Wars of the 1990s—or when there is mutual agreement on a divorce: here, the leading example would be the dissolution of Czechoslovakia (back) into the Czech Republic and Slovakia in January 1993. Existing states still put up legal barriers, and sometimes force of arms, against the secession of any part of their territory or the people inhabiting it: the US Civil War is only the most conspicuous instance of such resistance. One revealing index of the international consensus on these matters is that there is still no right to declare independence unilaterally, nor is there likely to be as long as most “peoples” are organized politically into sovereign territorial states. Those Catalan separatists who were imprisoned by the Spanish government or who fled their country after making such a declaration in 2017 can testify to how rigid that norm remains.

The US Declaration of Independence did nonetheless create both an encouraging example and an elusive ideal for later self-determination movements. It was encouraging because, in retrospect, it appeared to have succeeded: “one People,” organized into thirteen “Free and Independent States,” did in fact break away from their British brethren, did dissolve their formal political bands, and did gain international recognition from other powers of the earth, among them Morocco, France, the Dutch Republic, and ultimately Britain. Yet the Declaration was elusive, and even possibly illusory, because that unilateral declaration could not assert independence without, at a minimum, military force, financial muscle, diplomatic support, and international recognition behind it. As the French theorist Jacques Derrida noted in 1976, the Declaration rested on a paradox: only if the United States was (or were) already free and independent could they declare their independence. Merely being determined to assert oneself has never been sufficient to ensure self-determination.

The Declaration was also opaque, even obfuscatory, about just which “self” sought self-determination. The document begins by speaking of “one People” but ends by declaring the independence of thirteen states that now formed the (plural) United States of America. (Insofar as this was the first public statement of that name, the Declaration was in effect the US’s birth certificate.) But who were the “People”? Clearly not the one-third or so of the population who remained loyal to the British Crown, the loyalists. Perhaps not even another third who supported neither outright secession nor full independence. And certainly not the “merciless Indian savages” (as the Declaration opprobriously called them) or the half million enslaved persons in mainland British America, who were part of a quite different people, “a distant people . . . captivat[ed] & carr[ied] . . . into slavery in another hemisphere,” allegedly on the orders of King George III himself, as Thomas Jefferson put it in his original rough draft of the Declaration. Even in 1776, then, the question arose that always comes up in moments of self-determination: determination of exactly which self?

And yet, over time and around the world, the US Declaration increasingly came to animate and inspire other movements for self-determination. Of the 193 states currently represented at the United Nations, more than half have a document considered as a declaration of independence. The US Declaration was the first. No similar proclamation had previously announced an argument for secession in the specific language of statehood as independence: in 1776, that was still an avant-garde political idiom.

The Declaration inaugurated a novel political genre that would reappear especially in moments of the dissolution, forcible or otherwise, of empires: for example, during the collapse and redistribution of authority in Spanish America in the 1810s and 1820s; in the secession crisis in North America in the 1860s; amid the breakup of the European land empires after World War I and during decolonization in the decades after World War II; and as a result of the break-up of the Soviet Union. In some of these cases, the US Declaration provided a precise template and even borrowed language for self-determination, from Venezuela in 1811 to Vietnam in 1945, for instance; in most, it provided a more generic inspiration, as the declarations of independence proliferated globally even when not directly indebted to the American exemplar.

Self-determination can be a process or an event, an ideal or an idea. However we view it, any historical treatment shows that it has multiple, tangled roots. Even as an idea its origins can be traced back variously to Immanuel Kant and Johann Gottlieb Fichte in the German Enlightenment, to the Bolsheviks or to Woodrow Wilson in the early twentieth century, or to anti-colonial thinkers later in that century. The US Declaration of Independence preceded all of these, yet few of them (Woodrow Wilson excepted) would have acknowledged any debt to Jefferson and the Continental Congress for their own conceptions of self-determination. Other figures in movements for autonomy, independence, or self-determination did, of course. For the Hungarian independence leader, Lajos Kossuth, writing in 1849, the Declaration was “the noblest, happiest page in mankind’s history.” Almost a hundred years later, Hồ Chí Minh updated its words about individual equality and rights to assert in the Vietnamese Declaration of Independence of 1945 that “All the peoples on earth are equal from birth, all the peoples have a right to live, to be happy and free”: as clear a statement of the contemporary understanding of self-determination, as collective not individual, that one could wish for.

The US Declaration of Independence has only a contingent relationship with modern ideas of self-determination. The Declaration was not its only source or inspiration: many, perhaps most, self-determination movements since 1776 have proceeded without any reference to it. It did not use the specific language of self-determination, even if it did speak of the necessity for peoples to assume a “separate and equal Station” among the “Powers of the Earth.” Indeed, it could hardly have spoken that language, which post-dated 1776 and only gained global prominence almost a century and a half later. If self-determination did not originate with the Declaration, it would still be fair to say that later self-determination magnified the importance of the Declaration, not just as a statement of individual rights and only for Americans, but as a charter of the rights of peoples all around the world.

David Armitage is the Lloyd C. Blankfein Professor of History at Harvard University and an affiliated faculty member at Harvard Law School. Among his eighteen books to date, as author or editor, are The Declaration of Independence: A Global History (2007), Foundations of Modern International Thought (2013), The History Manifesto (with Jo Guldi, 2014), and Civil Wars: A History in Ideas (2017).