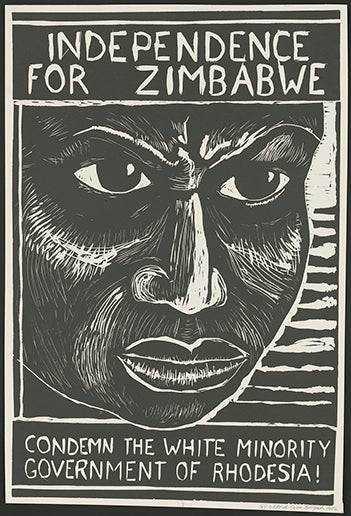

The Unilateral Declaration of Independence in Southern Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe)

by Eliakim Sibanda

The Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) was the most polarizing event in the colonial history of Zimbabwe. Locally, regionally, and internationally, it sharpened differences of opinion with respect to independence, especially along racial lines. It also deepened the Cold War in the region, as most Western countries stood behind the regime of Prime Minister Ian Douglas Smith, which was responsible for declaring the UDI. The Eastern Bloc supported the African nationalists who fiercely condemned the UDI, and used that support to agitate for majority rule. While responses were varied among African nationalists, at home and abroad, the majority strongly opposed and condemned the UDI.

The Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) was the most polarizing event in the colonial history of Zimbabwe. Locally, regionally, and internationally, it sharpened differences of opinion with respect to independence, especially along racial lines. It also deepened the Cold War in the region, as most Western countries stood behind the regime of Prime Minister Ian Douglas Smith, which was responsible for declaring the UDI. The Eastern Bloc supported the African nationalists who fiercely condemned the UDI, and used that support to agitate for majority rule. While responses were varied among African nationalists, at home and abroad, the majority strongly opposed and condemned the UDI.

On November 11, 1965, a Rhodesian White minority government led by Ian Smith in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) declared unilateral independence from Great Britain, ostensibly to preserve “justice, civilization, and Christianity” as well as to defend the country and the world against communism. This declaration created a seemingly intractable colonial and foreign policy crisis for the British government, and immediately put it at loggerheads with newly independent African countries in the 1960s. Up to the time the Smith government declared the UDI, Southern Rhodesia had been effectively self-governing, and was very close to attaining the status of full dominion like the older Commonwealth countries—Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Thus, the UDI is one of the few watershed events in the history of Zimbabwe. It is considered by most nationalist historians to be the spark that triggered the liberation struggle.

Background

Founded by Cecil John Rhodes, a British-born businessman, the British South Africa Company (BSAC) colonized Southern Rhodesia in 1890. Rhodes and his company had been granted a colonization charter by the Queen of England, through the British government. Under BSAC rule, the territory was renamed Rhodesia (from the name Rhodes). The British government revoked the charter in 1923, prompting the settlers to vote for self-rule,[1] thus creating the colony of Southern Rhodesia.[2] The constitution of 1923, granted by letters patent,[3] placed political power in the hands of the White settlers at the expense of the Africans, who were systematically disenfranchised through economic and educational clauses in the constitution. Since the 1923 constitution did not grant Southern Rhodesia full internal self-government,[4] successive Southern Rhodesian governments still maintained their ties with the British crown, on which they relied for both economic and political support.

Between 1953 and 1963, the settler government formed a federation of British colonies in Central Africa, including Nyasaland (Malawi), Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), and Southern Rhodesia. It became known as the Central African Federation. From the early 1960s, the British government succumbed to international pressure for the independence of African countries and the introduction of majority rule. In 1961, Britain introduced a constitution in Southern Rhodesia, which granted Africans a Bill of Rights, which some Whites considered gave Africans rights they did not deserve. Unlike apartheid in South Africa, which did not envisage any African rule, the 1961 constitution provided for unimpeded progress toward African majority rule, and also offered a way for Africans to qualify to vote, based on education and property ownership. Britain adopted a policy referred to as “No Independence Before Majority Rule” (NIBMAR), which demanded all its colonies go through the process of instituting majority rule before political independence could be attained.[5] This policy meant that Africans, who were always the majority population, would be handed power through the process of democratic elections. Zambia (1963) and Malawi (1964) were the first to attain their independence, marking the end of the federation system that had been adopted in 1953.

The Political Atmosphere Prior to the UDI

The period prior to the UDI was characterized by increased political activity both within Southern Rhodesia and beyond. Ghana had attained its political independence in March 1957, becoming the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to achieve self-rule. The independence of the two neighboring countries, Zambia and Malawi, led to growing nationalist sentiment among Africans in Southern Rhodesia, while also sounding an alarm in the White population that feared losing power. According to the Commonwealth, however, White supremacist aspirations in Central and Southern Africa were doomed.[6] The core mandate of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) [now called the African Union (AU)], the continental bloc established in 1963, was to assist nationalist groups gain independence from their European colonizers. The period between 1957 and 1965 also saw the formation of militant nationalist movements, including the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), led by Joshua Nkomo, and the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), led by Ndabaningi Sithole. With pressure also from African countries that had already attained independence, the nationalist movements began massive political campaigns to win the support of the African people, particularly the peasants in the rural areas. It thus became clear to everyone that colonialism was nearing its end in Southern Rhodesia.

Elections in 1962 resulted in the Rhodesian Front (RF) winning power. Led initially by Winston Field, Ian Smith, an extreme White supremacist, took over in 1964. During Smith’s reign, the radical White minority embarked on a campaign to hinder (if not block) all prospects of African rule in Southern Rhodesia. As a prelude to the UDI, Smith asked the governor of Rhodesia, Humphrey Gibbs, to sign a proclamation introducing a state of emergency. The proclamation was supported by an affidavit from the commissioner of police.[7] In an act of deception, “Smith assured Gibbs that this was not a prelude to a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) and the governor was therefore persuaded to sign the proclamation, which was issued two days later.”[8] Prior to the announcement of the UDI, the Rhodesian Front government had imprisoned leading nationalist figures, including Joshua Nkomo (ZAPU) and Ndabaningi Sithole (ZANU), making clear its intention to suppress all nationalist movements.

International, Regional, and Internal Responses to Smith’s UDI

Despite Smith’s attempts to blame Great Britain for being uncooperative, international responses to the UDI were mostly in opposition. Though Smith wanted the UDI to consolidate his power, the British government imposed an economic embargo on the colony in response. It also considered military intervention to stop the UDI, in both October 1965 and October 1966. Smith however shrewdly dismissed the likelihood of British military intervention. After all, Rhodesia was on Britain’s back burner, as it was managing more important crises—the Dhofar armed conflict, the developing war in Vietnam, and more generally, competition for military supremacy against Russia and China.

Closer to home, ZANU and ZAPU, the principal Rhodesian nationalist parties, vigorously opposed the UDI. They pressured the Organization for African Unity, the Commonwealth, and the United Nations to urge Britain to put an end to the UDI by force, if necessary. Regionally, however, while the Organization of African Unity opposed the UDI, South Africa’s White population endorsed it. Among the older Commonwealth countries, only Canada consistently stood strongly against the declaration, and presented proposals meant to end the stalemate.

The British government’s response to the Unilateral Declaration of Independence was strategic, not only to protect the White population in Rhodesia, but also to protect its economic interests in the region. It did not appeal to the UN for full-blown sanctions against Rhodesia, fearing the UN might then end up sanctioning South Africa, a staunch supporter of the UDI, too. This would have interfered with British interests in South African minerals as well as other investments. Britain also feared that antagonizing South Africa might trigger a war between South Africa and Zambia, thereby undermining the security of its Zambian copper supply.

The Unilateral Declaration of Independence, therefore, was a serious political gaffe by the colonial Rhodesian Front government under Prime Minister Ian Smith. Besides the immediate economic consequences for Rhodesia of international disapproval, the UDI contributed to an increasingly vicious domestic conflict with nationalist movements over the next fifteen years, until full independence was finally achieved—by other means—through the founding of Zimbabwe in 1980.

Eliakim Sibanda is Professor of History and Head of Graduate Studies at the University of Winnipeg. He is the author of The Zimbabwe African People’s Union, 1961–1987: A Political History of Insurgency in Southern Rhodesia (Africa World Press, 2005).

[1] See V. Kwashirai, Green Colonialism in Zimbabwe, 1890–1980 (Amherst, New York: Cambria Press, 2009), p. 3.

[2] United Nations Department of Political Affairs, Decolonisation 2, no. 5, Issue on Southern Rhodesia (July 1975): 5.

[3] Letters patent is a legal instrument issued by government that conveys the right to certain organizations. The Free Dictionary: Legal Dictionary, http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Letters+Patent .

[4] Decolonisation 2, no. 5 (July 1975): 5.

[5] R. W. Copson, Zimbabwe: Background and Issues (New York: Novinka Books, 2006), p. 5.

[6] The Parliamentary Elections in Zimbabwe, 24–25 June 2000: The Report of the Commonwealth Observer Group (London: Commonwealth Secretariat, 2000), p. 5.

[7] Carl Peter Watts, Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence: An International History (London: Palgrave, 2002), p. 2.

[8] Watts, Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence, p. 2.