The Repeal of Asian Exclusion

by Jane Hong

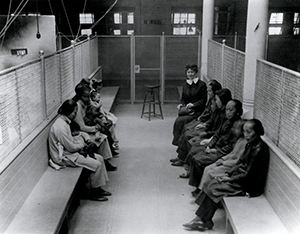

The United States excluded Chinese people beginning in the late nineteenth century and expanded its ban to all Asians in the 1917 and 1924 Immigration Acts. In addition to creating a national origins quota system best known for privileging northern and western Europeans over southern and eastern Europeans for the purposes of entry, the 1924 Immigration Act barred all Asians from permanent settlement in the United States on the grounds that they were “aliens ineligible to citizenship.” Thus it codified into law Asians’ status as perpetual foreigners.

The United States excluded Chinese people beginning in the late nineteenth century and expanded its ban to all Asians in the 1917 and 1924 Immigration Acts. In addition to creating a national origins quota system best known for privileging northern and western Europeans over southern and eastern Europeans for the purposes of entry, the 1924 Immigration Act barred all Asians from permanent settlement in the United States on the grounds that they were “aliens ineligible to citizenship.” Thus it codified into law Asians’ status as perpetual foreigners.

Both the rise and fall of Asian exclusion laws in the US reflected Asia’s weakness relative to Western powers generally, and the growing global status of the United States in particular. Asian countries and peoples as well as non-Asian advocates resisted the racism and stigma of exclusion laws from the beginning: they cited the negative impact on bilateral relations, economic partnerships, and even American missionary efforts to win Asian souls. But the US and other Western powers that had similar laws felt free to ignore them for decades.

American indifference started to become untenable during World War II. Restriction and exclusion previously compatible with US foreign policy goals did not align with the new objective of presenting the US as an antiracist and anticolonial democracy where all people could succeed regardless of race, ethnicity, or nationality. As Asian peoples began demanding their independence from Western imperial powers during and after World War II, pressure to modify or repeal racist immigration and naturalization laws mounted. As the Cold War contest intensified, Washington officials eager to “win the hearts and minds” of Asian and African peoples in its battle against Soviet and ultimately Chinese communism recognized the harm of racist immigration policies and took steps to address, at least, the appearance of racism. Since the goal was to make the US look racially inclusive, token quotas or symbolic reforms were sufficient, and policy changes need not increase Asian immigration in any meaningful way.

The geopolitical context and changing power dynamics created opportunities for repeal, but people made it happen. In a time of unprecedented US expansion in the Pacific between 1943 and 1965, a diverse group of advocates seized upon the political momentum and opportunities created by the interventions of the US in Asia to lobby for an end to America’s Asian exclusion laws. Only loosely associated with one another, they came to the cause for different reasons and with different goals but used the same foreign policy–based arguments to make their case. They included Asian officials who pursued repeal using formal and informal policy channels, a bipartisan network of US policymakers ranging from conservative Republican and former China missionary Walter Judd to liberal New York Democrat Emanuel Celler as well as American community organizations, church groups, and others. In letters, petitions, public testimony, and personal appeals, their arguments referenced military expediency and US self-interest.

The repeal of Chinese exclusion during WWII marked the first and most important milestone. The Magnuson Act, popularly known as the “Chinese Exclusion Repealer,” launched the longer movement by inspiring repeal campaigns by and on behalf of other Asian groups. The formal alliance of the United States with China in the war against Japan offered a unique opportunity. A White American group called the Citizens Committee to Repeal Chinese Exclusion led the way; they mobilized and galvanized support from strategic individuals including President Franklin Roosevelt himself. Framing Chinese exclusion repeal as necessary to win the war against Japan was politically powerful, as winning the war was paramount in the minds of both Washington officials and the American public. Even the most reluctant congressional lawmakers felt hard-pressed to deny a Chinese ally under duress lest it undermine or otherwise delay the goal of Allied victory. Nevertheless, the measure had met vehement opposition within Congress, particularly among southern Democrats who worried that loosening restrictions for one group would “open the floodgates” to the entry of other Asian peoples.

These predictions were not wrong. Other Asian groups and their allies quickly began making claims of their own. In separate efforts, Indians and Filipinos in the US launched campaigns to secure citizenship rights and token immigration quotas. These featured private, direct lobbying of congressional lawmakers by Indians in the British colonial government and Filipinos in the US colonial government as well as by working-class migrants living in the United States. For the latter, repeal was largely an economic concern, as citizenship eligibility would qualify them for federal work programs and other relief reserved for US citizens. But, like their predecessors, most couched their arguments in terms of US foreign policy interests. Against the backdrop of growing tensions between the US and the Soviet Union, they stressed Washington’s need to court the loyalties of Asian peoples on the cusp of gaining independence from their Western colonizers. By ending Indian and Philippine exclusion, supporters of repeal argued, Washington could demonstrate its support to newly independent Asian peoples and harden them against communism. These arguments succeeded with the passage of the Luce-Celler Act in 1946, which granted small immigration quotas to Indians and Filipinos and made both groups eligible for US citizenship.

Passed during the Korean War, the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act formally ended Asian exclusion as a feature of US immigration policy, but the legislation’s mixed provisions reflected its fundamental character as a Cold War national security measure. On the one hand, the act ended Asian exclusion by giving Asian countries token immigration quotas of 100 to 185 per year. It also eliminated race as a basis for eligibility to naturalize as a US citizen. At the same time, the law expanded the power of the federal government to exclude, deport, and detain aliens deemed subversive or seen as holding subversive views. In this regard, the legislation reflected Washington’s overriding obsession with containing communism both at home and abroad in Asia.

The nominal quotas in the Magnuson Act, the Luce-Celler Act, and the McCarran-Walter Act did little to increase the number of Asians entering the United States. By contrast the 1965 Immigration and Nationality, or Hart-Celler, Act marked a watershed in American history. It abolished the national origins quota system and created in its place a preference system based on family reunification and skills. The impact was transformative, even if it was largely unintended. When designing the law to prioritize the migration of family members, even supporters of the bill predicted that it would do little to change the racial composition of the nation. Since more than eighty percent of immigrants came from Europe, it was expected that most of the immigrants admitted under the new law would also come from Europe. Yet that is not what happened, as few Europeans took advantage of the law while many people in Asia and Latin America did. In the 1950s, 153,000 immigrants (or 6% of the overall flow) entering the United States were of Asian descent; by the 1970s, those numbers had risen to 1.6 million or 35% of immigrants, and they have continued to grow ever since.[1] As of 2022, China and India are the largest sending countries of migrants to the United States, sending more than Mexico. By current projections, the Asian American population will reach 38 million, or one in ten Americans, by 2050. None of this would have been possible without the mid-twentieth-century movement that repealed Asian exclusion. While US foreign policy concerns were never themselves about inclusivity or racial progress, but rather about US global power and empire, the laws meant to support them nonetheless changed the racial composition of the nation.

Jane Hong is an associate professor of history at Occidental College and the author of Opening the Gates to Asia: A Transpacific History of How America Repealed Asian Exclusion (University of North Carolina Press, 2019). She received a PhD from Harvard and a BA from Yale. Her current project explores how post-1965 immigration changed US evangelicalism. Hong appears in Asian Americans (PBS, 2020), serves on the editorial board of the Journal of American History, and has written for the Washington Post and Los Angeles Times.

[1] Figures taken from Charles B. Keely, “The Immigration Act of 1965,” in Hyung-Chan Kim, ed., Asian Americans and Congress: A Documentary History (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996), pp. 530–532.