파도와 메아리: Waves and Echoes of Korean Migration to the United States

by Kira Donnell, Soojin Jeong, and Grace J. Yoo

According to the 2020 US Census, 1.9 million Korean Americans reside in the United States. Among Asian Americans, they are the fifth-largest ethnic group and primarily reside in California, New York, Hawaii, and Texas. [1] This essay provides an overview of Korean immigration to the United States and the key moments and stories that define the Korean American experience.

First Wave

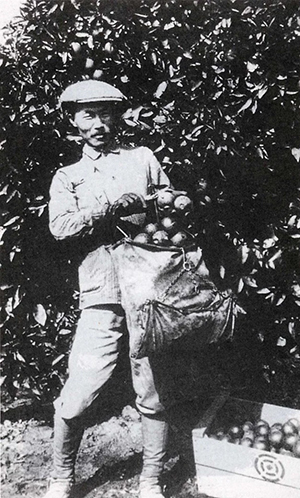

The first wave (1903–1905) of Korean migrants were mostly men who worked as contract laborers in the sugar cane fields in Hawaii and migrant farm workers in California. As “a people without a country” under extreme colonial exploitation by the Japanese Imperial government, 7,000 Korean immigrants arrived before the Korean government ended emigration in response to pressure from Japan. [2] Under the Gentlemen’s Agreement (1908) between Japan and the US, all migration of Korean laborers was halted.

The first wave (1903–1905) of Korean migrants were mostly men who worked as contract laborers in the sugar cane fields in Hawaii and migrant farm workers in California. As “a people without a country” under extreme colonial exploitation by the Japanese Imperial government, 7,000 Korean immigrants arrived before the Korean government ended emigration in response to pressure from Japan. [2] Under the Gentlemen’s Agreement (1908) between Japan and the US, all migration of Korean laborers was halted.

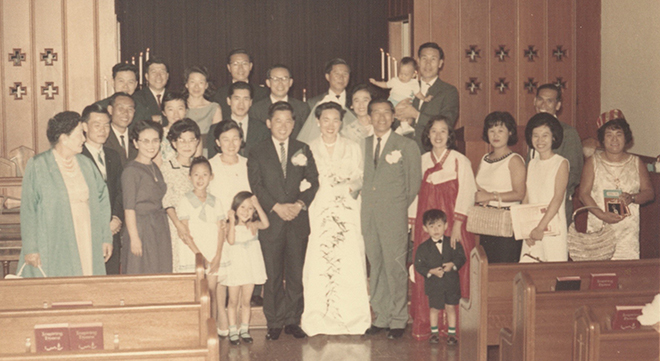

Between 1910 and 1924, Korean women arrived to meet and live with their Korean laborer spouses through the picture marriage system that took advantage of US immigration policies and the Korean custom of arranged marriage. [3] As exclusionary laws barred Korean women’s entry to the United States, these women married the Korean laborers in Hawaii and California by proxy after exchanging pictures and letters through local matchmakers in Korea. Many brides carried their dream of an education in “the wonderful land of freedom,” yet they faced the realities of immigrant life, often marrying men much older than they were. They not only worked in the farms and family-owned small businesses, but also sustained the daily lives of the early Korean community through their domestic works.

Because of the picture brides, Korean immigrant families formed. Political organization through Korean Christian and Methodist churches became stronger in the diasporic community as Korean immigrants worked alongside political leaders such as Ahn Chang-ho, who immigrated to the US in 1902 and helped form the Korean provisional government in Shanghai. [4] The Korean immigrants financed the independence movement in their motherland despite the severe working conditions and hardships in the hostile environment of the US.

Second Wave

Between 1945 and 1965, the second wave of Korean immigration occurred. Two interrelated things characterized this wave. First, the Immigration Act of 1924 restricted Korean immigration and marginalized those Koreans living in America by preventing their naturalization as citizens. Second, the involvement of the United States in the Korean War directly influenced the second wave of migration.

The Korean War, which occurred between 1950 and 1953, devastated the Korean Peninsula and solidified the ties between the United States and South Korea. There were 1.3 million casualties, ten million families were separated, and 100,000 children were orphaned during the Korean War in South Korea. [5] Given the unequal power dynamic between the United States and South Korea, these conditions directly informed and reflected the populations of Koreans who immigrated during the second wave.

Military wives, or “war brides,” were women who married US soldiers stationed in South Korea. Between 1953 and 1989, 100,000 women migrated to the United States with their American husbands. [6] The 1945 War Brides Act, designed to allow US soldiers to bring their European wives to the United States during World War II, allowed thousands of South Korean women to migrate as well. These military wives faced ostracism and discrimination from both Koreans who disapproved of the women’s fraternizing with US soldiers and Americans who saw the Korean wives as foreigners and outsiders.

Students were the second major group of Korean immigrants during this wave. Following the Korean War, the United States allocated $60 million for Korean educational reconstruction projects. [7] Between 1953 and 1980, 15,000 Korean students arrived in the United States through educational exchange programs. [8] Less than 10% of the students in these educational programs returned to South Korea. [9] The vast majority opted to remain in the United States.

Students were the second major group of Korean immigrants during this wave. Following the Korean War, the United States allocated $60 million for Korean educational reconstruction projects. [7] Between 1953 and 1980, 15,000 Korean students arrived in the United States through educational exchange programs. [8] Less than 10% of the students in these educational programs returned to South Korea. [9] The vast majority opted to remain in the United States.

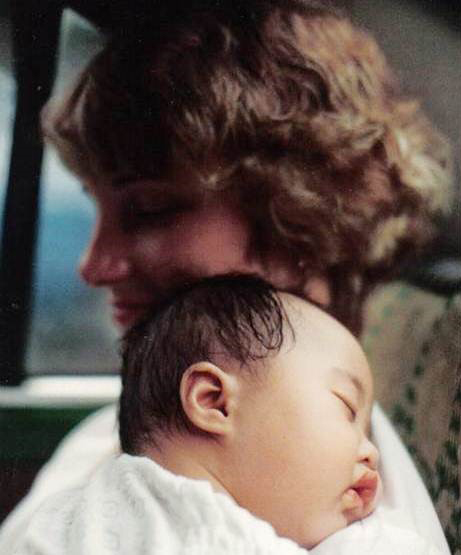

The third major group consisted of Korean adoptees: Korean children orphaned by war and/or mixed-race children fathered by US soldiers who were subsequently adopted into American families. In the early days of transnational Korean adoption, proxy adoptions and the sponsorship of individual laws by adoptive families’ representatives in Congress allowed a handful of Korean orphans to find new homes and families in the US. Adoption agencies like Holt Adoption Program lobbied for immigration policy changes, and in 1961, adoptees were recognized as immediate relatives of US citizens, freeing them from immigration quotas. [10] Since 1950, 200,000 Korean children have come to the United States as transnational adoptees. [11]

Third Wave

Exclusionary immigration and citizenship policies aimed at Asians and the social, economic, and political conditions in Korea and the US have played a part in the ebb and flow of Korean migration to the US. Korean immigration increased dramatically with the passage of the Immigration Act of 1965, which was due in part to the Civil Rights Movement and post-WWII international relations that abolished the racial quotas that had excluded Asian immigrants for decades. The Immigration Act of 1965 allowed permanent residents and US citizens to petition for their relatives, especially healthcare professionals and technical workers. Second wave war brides and students played a significant role in the development of the third wave Korean immigration as they were able to sponsor their families. Economic, political, cultural, and military relations between South Korea and the US as well as social developments in the US worked as push and pull factors for immigration during this time.

During the third wave, there were multiple key historical moments for Korean Americans. In 1973, a Korean immigrant, Chol Soo Lee, faced a wrongful incarceration for a gang killing in San Francisco’s Chinatown. He was sentenced to life in prison and killed a fellow prison inmate in self-defense, which resulted in his transfer to death row. Spearheaded by Korean American investigative journalist Kyung-Won (“K. W.”) Lee and the Korean American community, Chol Soo Lee’s case began to galvanize other Asian American activists. United in their demand for justice, the movement to free Chol Soo Lee became the first pan–Asian American social movement in which Korean Americans participated. [12]

Another major historical moment for Korean Americans was “Sa-I-Gu” (which translates to 4/29): the 1992 Los Angeles Civil Unrest. In response to the Rodney King court ruling, African Americans and other Los Angeles residents took to the streets in protest, which soon escalated into chaos. The Los Angeles Koreatown area experienced the brunt of the destruction with $770 million in material loss and damage. [13] The psychological and economic devastation of Sa-I-Gu served as a catalyst for political awakening in the Korean American community.

Fourth Wave

Between 2010 and 2020, there was a decline in Korean migration, which can be attributed to multiple social and economic factors in South Korea’s economy. Despite this, there has been a wave of families who have immigrated. Intent on providing their children with the best educational opportunities they can and avoiding the notoriously demanding South Korean education system, gireogi gah-jok, or “wild goose families,” immigrate to the US for K–12 education with mothers and children living abroad while fathers financially support the family from Korea. [14]

For over a hundred years, Koreans have made homes, lives, and identities for themselves in America. In recent years, Korean culture has increased in visibility and impact across the world. Dubbed Hallyu, or the Korean Wave, the migration of Korean pop culture is a reflection of globalization that has been aided by digital technologies and social media. Korean pop music, films, television dramas, and food are breaking into mainstream American culture. In turn, America’s interest, piqued by BTS, Squid Game, and Parasite, has shed new light on Korean American communities, culture, and history. As society is changing, we cannot predict what the next hundred years of the Korean American experience might become, but we can expect that the migrations of people and the exchange of ideas and cultures may continue to have profound and lasting impacts.

Selected Bibliography

Foster, Jenny Ryun, Frank Stewart, and Heinz Insu Fenkl, eds. Century of the Tiger: One Hundred Years of Korean Culture in America, 1903–2003. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press, 2003.

Lee, M. P. Quiet Odyssey: A Pioneer Korean Woman in America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1990.

Oh, Arissa. To Save the Children of Korea: The Cold War Origins of International Adoption. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015.

Sunoo, Sonia Shinn. Korean Picture Brides, 1903–1920: A Collection of Oral Histories. Bloomington, IN: Xlibris US, 2002.

Yuh, Ji-Yeon. Beyond the Shadow of Camptown: Korean Military Brides in America. New York, NY: New York University Press, 2002.

Kira Donnell, PhD is lecturer faculty in Asian American studies and the faculty director of Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion at the Center for Equity and Excellence in Teaching and Learning at San Francisco State University.

Soojin Jeong, MA is a doctoral student in East Asian studies at the University of California Irvine. Her research is in Asian American literature and Korean studies.

Grace J. Yoo, PhD is professor of Asian American studies at San Francisco State University. She is the co-author of Caring across Generations: The Linked Lives of Korean American Families (New York University Press, 2014), editor of Koreans in America: History, Identity and Community (Cognella, 2012), and co-editor of the Encyclopedia of Asian Americans Today (Greenwood, 2009).

[1] “Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month: May 2022,” United States Census Bureau, April 18, 2022. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2022/asian-american-….

[2] Wayne Patterson, The Korean Frontier in America: Immigration to Hawaii, 1896–1910 (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 1988), p. 1.

[3] Erika Lee and Judy Yung, Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 199.

[4] Jiwon Kim, “Korean Pioneer Women: Picture Brides and the Formation of Upwardly Mobile Korean Families in California, 1910s–1930s,” Korea Journal, vol. 60, no. 1 (2020): 207–238.

[5] Bruce Cumings, The Korean War: A History (New York, NY: Random House Publishing Group, 2011), p. 35.

[6] Ji-Yeon Yuh, Beyond the Shadow of Camptown: Korean Military Brides in America (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2002), p. 2.

[7] James Sang Chi, “Teaching Korea: Modernization, Model Minorities, and American Internationalism in the Cold War Era,” PhD diss. (University of California, Berkeley, 2008) p. 277.

[8] James Sang Chi, “Teaching Korea,” pp. 283–84.

[9] James Sang Chi, “Teaching Korea,” pp. 283–84.

[10] Arissa Oh, To Save the Children of Korea: The Cold War Origins of International Adoption (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015), p. 150.

[11] Kira Donnell, “Orphan, Adoptee, Nation: Tracing the Korean Orphan and Adoptee through South Korean and American National Narratives,” PhD diss. (University of California, Berkeley, 2019), p. 2.

[12] Grace J. Yoo, Mitchel Wu, Emily Han Zimmerman, and Leigh Saito, “Twenty-Five Years Later: Lessons Learned from the Free Chol Soo Lee Movement,” Asian American Policy Review 19 (2010).

[13] Elaine Kim, “Home Is Where the Han Is,” Social Justice 20, nos. 1–2 (1993): pp. 1–22.

[14] Se Hwa Lee, Korean Wild Geese Families: Gender, Family, Social, and Legal Dynamics of Middle-Class Asian Transnational Families in North America (Latham, MD: Lexington Books, 2021).