Indians in the United States: Movements and Empire

by Sherally K. Munshi

Until the turn of the twentieth century, there were relatively few restrictions on international migration. European imperialism and settler colonialism were sustained by mass migration—both the “free” migration of European settlers and forced migration of enslaved Africans, criminal convicts, and others. The transatlantic slave trade alone brought an estimated 11 million Africans to the Americas. After the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade, millions of Chinese and Indian laborers were transferred to work in European colonies across the globe. Settler colonialism involved not just mass migration, but also the mass displacement and elimination of indigenous peoples.

While European expansion set the world in motion, it was the free migration of a few thousand Asians to America that gave rise to modern immigration controls. In the United States, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 holds the distinction of being one of the first laws to substantially restrict mass immigration, and the first to do so on the basis of racial or national difference. Until then, migration from China to the United States had been governed by mutual agreement—treaty. But in the Chinese Exclusion Cases, the Supreme Court asserted for the first time that Congress had an “absolute and unqualified” right to exclude and deport foreigners, “however it might see fit.”[1] The Court held that Congress’s power to restrict migration was essential to national integrity and could not be limited by treaty—or by the Court itself. Though the crude racism expressed in the Chinese Exclusion Act now appears to most Americans as an embarrassing wrong that we can consign to the past, the unqualified power to restrict migration remains at the foundation of contemporary immigration law.

Less familiar to most Americans is the brief and tumultuous history of Indian immigration to and exclusion from the United States in the early twentieth century. After the United States closed its borders to Chinese immigrants, shipping companies filled their manifests with Indian immigrants, who quickly found employment in the agricultural fields and lumber mills of the Pacific Northwest. But almost as soon as they arrived, Indians, like the Chinese before them, became the targets of brutal violence. In 1907, for instance, a mob of 500 White laborers in Bellingham, Washington, descended upon a community of Indian laborers, pulled them from their work, burned their homes, and forced them onto trains bound for Canada. While there were never more than a few thousand Indians in the United States during this era, sensational reports warned of a new Asian invasion, this time a “tide of turbans.”[2]

Around 1910, exclusionists in California began calling for a “Hindu” exclusion bill, roughly modeled after the Chinese Exclusion Act. Though the Supreme Court maintained that Congress had broad authority to restrict immigration—“however it may see it fit”—efforts to enact another crudely racist immigration law were frustrated by a diplomatic reality. Indians were British subjects and, by treaty, guaranteed the same rights of entry as other British subjects. Some US officials hoped the British government would cooperate in restricting emigration from India, but British officials were wary of enflaming resentment. British attempts to restrict Indian migration to South Africa, a British dominion, had enraged Indians across the diaspora, galvanizing an increasingly transnational movement for Indian independence.[3]

Officials in the United States also recognized that “a rising tide of color against white world-supremacy” had begun to transform the international landscape.[4] Japan’s defeat of the Russian navy in 1904 represented a powerful challenge to Anglo-American supremacy in the Pacific and energized movements against imperialism across Asia. Asserting its newfound power, Japan had begun to challenge discriminatory laws in the United States, and the more circumspect members of Congress preferred to avoid “offending” Japan and others. While proposals for a Hindu exclusion bill languished in Congress, between 1910 and 1917, immigration officials made exhaustive use of available regulations and rationale to limit the number of Indians entering the country, inflating concerns, for instance, that Indian immigrants were diseased or likely to become “public charges.”

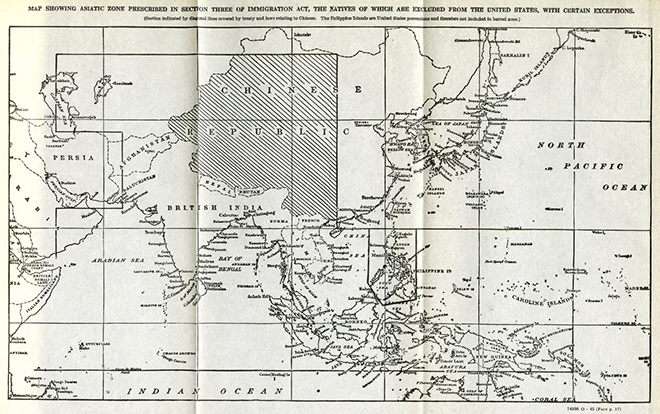

Eventually, in 1917, exclusionists found a way around these diplomatic concerns: they passed a law banning individuals from an invented “Asiatic Barred Zone.” Unlike earlier versions of a proposed Hindu exclusion act, the Asiatic Barred Zone Act restricted Indians not on the basis of their identity—defined either in terms of race or nationality—but their place of origin. As one Congressman explained, because the State Department worried that another racial ban might offend Japan, “instead of describing the excluded persons as ‘Hindus,’ [Congress] took the same people within geographic lines and excluded them.”[5] By recasting a racial ban in geographic terms, explained another, the act could “be swallowed without naming anyone.”[6] Indeed, a hundred years later, the Trump administration was able to enact a promised “Muslim ban” by recasting it as a ban on people from certain “territories.” The Muslim ban was upheld by the Supreme Court in 2018.

Many of the first Indians to reach the United States came as students and exiles, young men already active in the movement against British rule in India. They often arrived with a strong sense of identification with the United States, comparing their own struggle for independence from Britain with the American Revolution. But this identification soon gave way to disenchantment as they faced exclusion, exploitation, and routine humiliation.[7] Some of these immigrants realized that Indians perhaps had more in common with Black Americans in their shared struggle against White supremacy.[8] Others recognized that the United States had more in common with Britain than India. The United States itself had become an empire, seizing the Philippines among other territories after the Spanish-American War; its racist immigration policies bore a striking resemblance to those of Canada and Australia, British dominions; and it entered the world war as an ally of imperial Britain.[9]

Realizing that their humiliation in the United States was related to their status as colonized subjects, Indians on the West Coast began to dream of returning home to start a revolution. A coalition of students and laborers came together in 1913 to establish an organization called Ghadar, meaning “mutiny” or “revolt,” with the goal of bringing an end to British rule in India. An astonishingly energetic movement, Ghadar drew inspiration from and established connections with other anti-imperial and workers’ movements in the United States and around the world. It quickly came under the surveillance of British spies, with whom exclusionists in the United States eagerly collaborated.[10] In 1917, several Ghadarites were arrested and tried for violating the supposed neutrality of the United States in what was one of the most expensive trials in US history.[11] By that time, recognizing that the European war had provided an opportune moment to challenge the overstretched British empire, hundreds of Indians in the United States and Canada answered the call of the Ghadar Party and made the reverse journey to India.

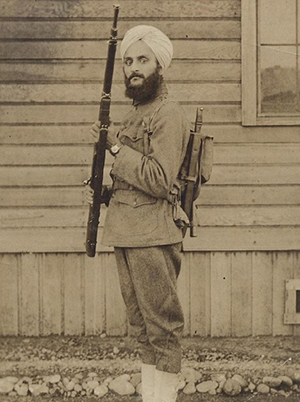

After the United States closed its doors to further migration from India, it sought to unsettle those who were already here. In an extraordinary campaign, the Department of Justice sought to cancel the citizenship of almost every Indian man who had been naturalized, claiming that he had been “racially ineligible” for naturalization.[12] In 1923, the Supreme Court was asked to consider whether Bhagat Singh Thind, a Punjabi Sikh, was “white” according to the terms of the Naturalization Act of 1790. Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice George Sutherland explained that although many individuals from India had proven themselves capable of cultural assimilation, Indians “retain indefinitely” their “physical group characteristics . . . [which] render them distinguishable” from White Americans.[13]

After the United States closed its doors to further migration from India, it sought to unsettle those who were already here. In an extraordinary campaign, the Department of Justice sought to cancel the citizenship of almost every Indian man who had been naturalized, claiming that he had been “racially ineligible” for naturalization.[12] In 1923, the Supreme Court was asked to consider whether Bhagat Singh Thind, a Punjabi Sikh, was “white” according to the terms of the Naturalization Act of 1790. Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice George Sutherland explained that although many individuals from India had proven themselves capable of cultural assimilation, Indians “retain indefinitely” their “physical group characteristics . . . [which] render them distinguishable” from White Americans.[13]

Though the Court limited its reasoning to Thind’s “racial difference,” Thind himself had come to the attention of naturalization officials who challenged his citizenship because he was an active member of the anti-imperial Ghadar movement.[14] In other words, he was thought unfit for citizenship not simply because he was racially distinguishable but because he and his counterparts embraced an anti-imperialism incommensurate with American national identity. In the decade after United States v. Thind was decided, scores of Indians were subject to denaturalization. A painful moment in American history, Indian Americans were denaturalized in spite of having assimilated by acquiring wealth, demonstrating patriotism, and disavowing political radicalism.

The bar against migration from Asia was finally abolished with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. But in its place, the act established more refined mechanisms for sorting between desirable and undesirable new immigrants by creating “preference” categories that favored immigrants with valuable skills and family ties. Asian immigrants have been able to take advantage of both preference categories to dramatically expand their presence in the United States, from less than 1 million in 1960 to 22 million in 2020.

As a category, “Asian American” is notoriously overbroad. Within that category, there is significant inequality among the different groups. While Asian Americans earn more than any other racial group in the United States, the average income among Asian American households varies widely—the median annual income for an Indian American household is more than twice that of a Burmese American household.[15] South Asian Americans are themselves a diverse group, one that includes refugees, border-crossers, and a large working class. But they are undoubtedly among the primary beneficiaries of immigration policies favoring high-skilled migration. In the past few years, roughly 75 percent of all visas allocated to high-skilled workers have been awarded to Indians, mostly men, mostly upper-caste Hindus.[16]

The success of Indian immigrants among tech workers is often touted, by Indians themselves, as a reason to “rationalize” America’s immigration system by expanding opportunities for skilled workers while restricting opportunities for others, especially poorer and vulnerable migrants. But the heightened visibility of Indians in certain industries and professions also obscures brutal forms of islamophobia, casteism, and patriarchy among Indians of the diaspora. The relative success of South Asians in the United States is not simply a story about racial progress or meritocracy; instead, it is primarily a story about selection.

Sherally Munshi is a professor of law at Georgetown University Law Center. She earned her JD from Harvard Law School and her PhD in English and comparative literature from Columbia University. Her scholarly interests include histories of race, empire, and migration.

[1] Chae Chan Ping v. United States, 130 U.S. 581 (1889); Fong Yue Ting v. United States (1889), 149 U.S. 698 (1893), 705–707.

[2] Herman Scheffauer, “The Tide of Turbans,” The Forum, vol. 43 (June 1910), 616–618.

[3] Sherally Munshi, “Race, Geography, and Mobility,” Georgetown Immigration Law Journal 30 (2016), 245–286, especially 261–276; Joan Jensen, Passage from India: Asian Indian Immigrants in North America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 139–162.

[4] Munshi, 269.

[5] Munshi, 272 (54 Congressional Record 205 [1916], statement of Senator Henry Lodge).

[6] Munshi, 275 (54 Congressional Record H1492–93 [1917], statement of California Representative John Raker).

[7] Manan Desai, The United States of India: Anticolonial Literature and Transnational Refraction (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2020), 6–20.

[8] Dohra Ahmad, Landscapes of Hope: Anti-Colonial Utopianism in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 3–10, 169–173.

[9] Sudhindra Bose, Mother America: Realities of American Life as Seen by an Indian (1934).

[10] Maia Ramnath, Haj to Utopia: How the Ghadar Movement Chartered Global Radicalism and Attempted to Overthrow the British Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 39, 44, 66–67; Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 45–81.

[11] Giles T. Brown, “The Hindu Conspiracy, 1914–1917,” Pacific History Review 17.3 (1948), 299–310.

[12] Hardeep Dhillon, “The Making of the Modern Alien & Citizen: Asian Immigration, Racial Capitalism, and US Law,” American Historical Review (forthcoming).

[13] United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, 261 U.S. 204 (1923), 215.

[14] Doug Coulson, Race, Nation, and Refuge: The Rhetoric of Race in Asian American Citizenship Cases (SUNY Press, 2017), 55–59.

[15] Abby Budiman & Neil G. Ruiz, “Key Facts about Asian Americans, a Diverse and Growing Population,” Pew Research Center (April 29, 2021), available at https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/29/key-facts-about-asian-americans/

[16] H-1B Petitions by Gender and Country of Birth, Fiscal Year 2019. US Citizenship and Immigration Services, available at: https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/data/h-1b-petitions-by-gender-country-of-birth-fy2019.pdf.