The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority

by Madeline Y. Hsu

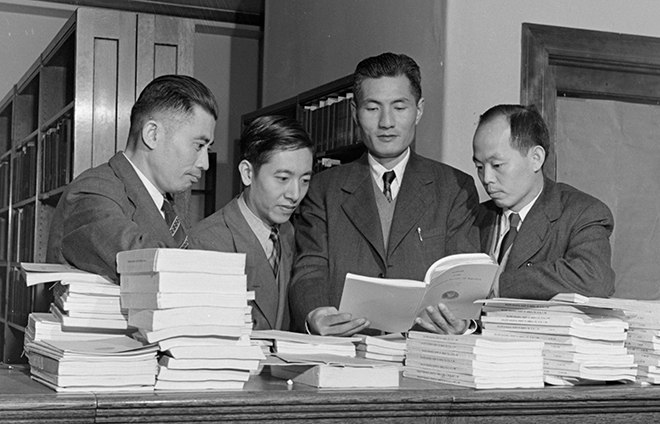

The United States harvested a bumper crop of good immigrants in 1955. About 1,000 highly educated Chinese gained citizenship, including acclaimed scientists, professionals, and entrepreneurs such as the architect I. M. Pei, the physicist T. D. Lee—who would win the Nobel Prize in 1957—and the computer pioneer An Wang.[1] This unprecedented peak in Chinese immigration was legalized by the US government in order to counter an appeal made by the newly communist Chinese government recruiting Chinese with practical knowledge and skills to return and help rebuild their ancestral homeland. Without this special program, this cohort of American-educated, occupationally accomplished individuals otherwise had almost no chance for settling permanently in the US, simply because they were Chinese. But by the 1950s, discriminatory citizenship and immigration laws were increasingly a liability for US foreign relations.  The Cold War intensified military and economic competition for the most educated and talented people in many fields, regardless of their race, while the Civil Rights Movement and the establishment of many independent Asian and African nations with decolonization applied pressure on the US to retreat from its segregationist practices. The ensuing struggle to reform immigration laws produced the 1965 Hart-Celler Immigration Act, which instead emphasized family reunification and skilled employment and remains the primary legal structure regulating immigration today. Chinese arriving as students, and their conversion into US citizens, figured prominently in the US racially, economically, and politically.

The Cold War intensified military and economic competition for the most educated and talented people in many fields, regardless of their race, while the Civil Rights Movement and the establishment of many independent Asian and African nations with decolonization applied pressure on the US to retreat from its segregationist practices. The ensuing struggle to reform immigration laws produced the 1965 Hart-Celler Immigration Act, which instead emphasized family reunification and skilled employment and remains the primary legal structure regulating immigration today. Chinese arriving as students, and their conversion into US citizens, figured prominently in the US racially, economically, and politically.

Chinese had been the earliest targets for restriction when the US began pursuing immigration regulation seriously. Asians had already been designated as racially unqualified for citizenship in the 1790 Nationality Act, which provided strong rationales for barring their immigration through 1952. Before the 1880s, Congress had enacted piecemeal immigration restrictions but without effective enforcement measures or agents. During the 1870s, Chinese restriction became a bipartisan consensus amid the worst economic depression in national history and the settling of national debates about ending slavery. A series of closely contested presidential elections drove both the Democratic and Republican Parties to court the electoral votes of then swing-state California. As the home and workplace for about 70 percent of the otherwise minuscule numbers of Chinese in the US, California led the anti-Chinese movement. The 1882 Chinese Restriction Act, later known more popularly as the Chinese Exclusion Law, barred entry to Chinese defined by race as unwanted, slavish, “coolie” competition for White laborers, with exemptions only for a handful of elites. This overtly racist law remained on the books until 1943 and laid the foundations for the steady expansion of federal powers, immigration laws, and enforcement measures characterizing border crossings today.[2] Chinese immigration plummeted. Most of the Chinese managing to enter did so by claiming fraudulent identities and statuses. These so-called “paper sons” lived in the shadows, constantly fearing detection and deportation, even as they pursued the better economic opportunities still to be found in the US.[3]

Most immigration histories understandably focus on the restrictive aspects of immigration laws because they impose severe inequalities and vulnerabilities on targeted categories of persons. In parallel, however, immigration laws also select for and privilege designated categories of persons and attributes with legal entry rights and pathways to citizenship. From the start, even the Chinese exclusion laws provided narrow legal exemptions for Chinese deemed beneficial to the US, such as merchants, diplomats, and students, based on class and their roles in maintaining international relations.

My 2015 book, The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority, focuses on Chinese who arrived in the United States seeking an education. They would shape major aspects of immigration law and society alongside their better-researched laborer contemporaries. The Chinese Educational Mission (1872–1881), for example, was the first international education program in the US, and many of its participants went on to spearhead major aspects of China’s industrial and financial modernization and foreign relations with the US. American missionaries and higher education leaders viewed educating Chinese as a benevolent, cheap, and effective way to exert US influence in China, an approach that the Department of State began coopting in the 1930s. Contradicting the racism of Chinese exclusion (1882–1943), Chinese students were welcomed and recruited to university and college campuses, enjoying dedicated scholarships and the support of foreign student services seeking to ensure they had positive experiences in the US to bring back to influence fellow Chinese. When the Institute for International Education started tracking foreign students in 1923, Chinese were always among the top three most numerous international student populations, and they remain the largest group today.

Until World War II, US-educated Chinese returned to China to shape its modernization and orientation to American values and world leadership. The alliances of global war remade this balance. China and the Chinese people became the most important allies of the US against Japan, a development that required the US to repeal Chinese exclusion and grant Chinese citizenship rights. Chinese students could not return home during the Japanese invasion (1937–1945) and the Chinese Civil War (1945–1949), so Congress authorized them to remain and work. When China became communist in 1949, forcing them to return became inhumane, impractical, and even dangerous when it involved individuals of great accomplishment, including scientists employed at cutting-edge research laboratories. The rocket scientist Qian Xuesen demonstrated the stakes. Qian arrived in the US as a student working with Enrico Fermi during the 1930s, began teaching at CalTech during the 1940s, and helped to found the Jet Propulsion Laboratories. He gained citizenship in 1949, but atrocious mismanagement of his effort to visit his father in China in 1950 led to his house arrest in the US and suspension from conducting research. By the time he appeared at the top of China’s list in a 1955 POW exchange, Qian was eager to leave the US and return to China, where he founded its robustly successful rocket program.

The gains, and losses, of Chinese human capital in 1950s America underscore the many key arenas of American life affected by immigration policy. The criteria used to select or reject immigrants reflect our fundamental national values regarding who we think we are as a people and the kinds of qualities we welcome or reject in potential fellow citizens. Shamefully, for most of our national history, race and national origins have been the main determinants for legal immigration and citizenship. Educated Chinese, however, and their burgeoning accomplishments as scientists, artists, entrepreneurs, and restaurateurs, and in hosts of other capacities, combined with their complex humanity and compatibilities with the US mainstream, pushed against these discriminations and demonstrated irrefutably the necessity of reforming US immigration laws to prioritize family relationships, individual potential for achievement, and shared political values.

Madeline Y. Hsu is the holder of the Mary Helen Thompson Centennial Professorship in the Humanities and a professor of history and Asian American studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of several books, including Asian American History: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2016), The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority (Princeton University Press, 2015), and Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration between the United States and South China, 1882–1943 (Stanford University Press, 2001).

[1] Shien-woo Kung, Chinese in American Life: Some Aspects of Their History, Status, Problems, and Contributions (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1962), 107.

[2] A few months later, Congress enacted the 1882 Immigration Act which barred entry to poor people, identified as those “likely to become public charges” (LPC). The 1892 Geary Act extended the Chinese exclusion laws and added enforcement measures such as requiring that Chinese register and bear documents proving legal entry or be subject to detention and deportation. In the ensuing decades, Japanese, anarchists, the illiterate, and persons from the Asiatic Barred Zone met with immigration restriction and exclusion, culminating in the most restrictive immigration law in US history, the 1924 Immigration Act, which imposed a global system of national origins quotas and barred entry to Asians as “aliens ineligible for citizenship.” Only northern and western Europeans retained relatively unrestricted entry rights while immigration plummeted to less than a quarter of previous levels.

[3] See my first book, Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration between the United States and South China, 1882–1943 (Stanford University Press, 2001).