James Forten, Sailmaker

by Julie Winch

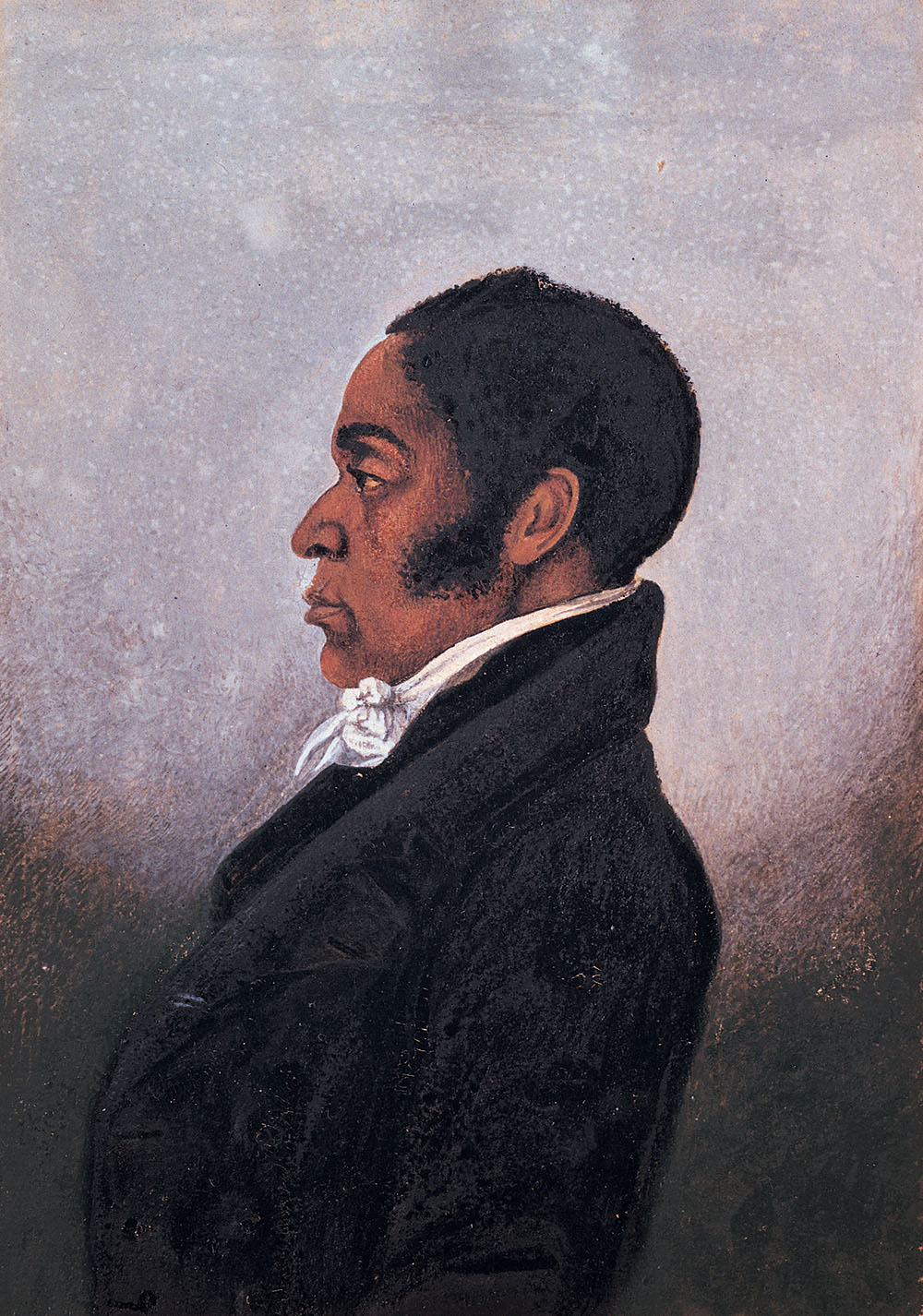

The White visitor headed up the stairs to the large open space above the storerooms and merchants’ offices on Philadelphia’s South Wharves and introduced himself to James Forten, the “gentleman of color” he had heard so much about. The year was 1834. Forten was sixty-eight and at the height of his prosperity. He had long since learned the wisdom of diversifying. He owned real estate. He held bank stock and shares in various enterprises in Philadelphia and beyond. However, he considered himself first and foremost a master craftsman. His sail loft was the beating heart of his business empire. For more than three decades, White shipowners and ship’s captains had recognized that Forten was the man to see when they needed new sails made or old ones refurbished. Few of them espoused the social agenda that mattered so much to him. They simply knew high-quality work when they saw it.

The White visitor headed up the stairs to the large open space above the storerooms and merchants’ offices on Philadelphia’s South Wharves and introduced himself to James Forten, the “gentleman of color” he had heard so much about. The year was 1834. Forten was sixty-eight and at the height of his prosperity. He had long since learned the wisdom of diversifying. He owned real estate. He held bank stock and shares in various enterprises in Philadelphia and beyond. However, he considered himself first and foremost a master craftsman. His sail loft was the beating heart of his business empire. For more than three decades, White shipowners and ship’s captains had recognized that Forten was the man to see when they needed new sails made or old ones refurbished. Few of them espoused the social agenda that mattered so much to him. They simply knew high-quality work when they saw it.

What struck the visitor as his new friend took him around the sail loft was that the workforce was racially integrated, and that harmony prevailed. James Forten explained that he had always hired on merit alone. “Here,” he observed, “you see what . . . ought to be done in our country at large.”[1]

The two men chatted for a while, and then the visitor headed home to set down on paper his impressions of what he characterized as “A Noble Example.” The sketch that appeared in the American Anti-Slavery Society’s journal, the Anti-Slavery Record, was brief—just a couple of paragraphs about Forten’s wealth and his commitment to racial equality. There was so much more the writer could have said.

James Forten was intimately acquainted with every square foot of his sail loft. He had first come there with his father, Thomas, when he was barely able to climb the stairs. In the late colonial era, when slavery was legal throughout British North America, the Fortens were an anomaly. They were Black and they were free. Thomas Forten could trace his paternal lineage back to his grandfather, who had arrived in Philadelphia on a slaving ship. That man’s son had secured his liberty. His son, Thomas, was freeborn. Thomas had married a free woman of color, Margaret, and their son, James, had been free from the day of his birth—September 2, 1766. Thomas was a journeyman sailmaker. Although his White employer, Robert Bridges, owned enslaved people, he acknowledged that Thomas was legally free, he paid him wages, and he probably acquiesced to Thomas’s wish to pass on his skill to his son. James literally learned the basics of sailmaking at his father’s knee.

James Forten’s education in the craft of sailmaking came to a temporary halt when he was seven. Thomas fell ill and died. A family friend, White Quaker abolitionist and educator Anthony Benezet, stepped in to help Margaret and her children, James and his sister Abigail. He found James part-time work, and he persuaded Margaret to enroll him in the Quakers’ African School. James proved an apt pupil, but after two years, his family’s worsening economic plight forced him to quit school and go to work full time. Once more, Benezet intervened, securing him a job clerking and cleaning for a White grocer.

What he saw and heard and experienced over the next few years affected James Forten profoundly as he grappled with the concept of a new nation and his own place within it. On July 8, 1776, two months short of his tenth birthday, he joined the crowd in the State House Yard (outside today’s Independence Hall) and heard the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence. His family stayed put through the British occupation of the city, weathering the changes taking place around them as best they could. Then, in the summer of 1781, with Philadelphia back under patriot control, James enlisted on board a commerce raider. Privateering captains eager for crew members seldom discriminated based on race because they simply could not afford to do so.

The privateer’s first cruise was very successful, with prize money for everyone, even a lowly “powder boy.” Back on shore, James Forten spent his fifteenth birthday watching as General Washington marched his troops through Philadelphia on their way to confront Lord Cornwallis’s forces at Yorktown, Virginia. What struck young James was the presence in Washington’s army of “several Companies of Coloured People, as brave Men as ever fought.”[2] He would soon prove his own commitment to the cause of independence.

James Forten’s second privateering cruise ended swiftly and disastrously. Just one day out of Philadelphia, his vessel was captured, and he and the rest of the crew found themselves confined below decks on a British warship. As luck would have it, HMS Amphion’s captain, John Bazely, had his twelve-year-old son with him. Henry was not taking well to life at sea. He needed a companion close to his own age. Captain Bazely spotted James Forten. He ordered him to be released and told him to keep an eye on Henry. Over the next few weeks, as the Amphion headed for the British-held port of New York, an unlikely friendship developed between the two boys. Captain Bazely approved, and he invited James to come to England to be educated with Henry, provided, of course, that the young Philadelphian declare himself a loyal British subject. Although he accepted that the offer was genuine, and that Bazely was not plotting to enslave him, James Forten insisted that he simply could not betray his country. He was an American.

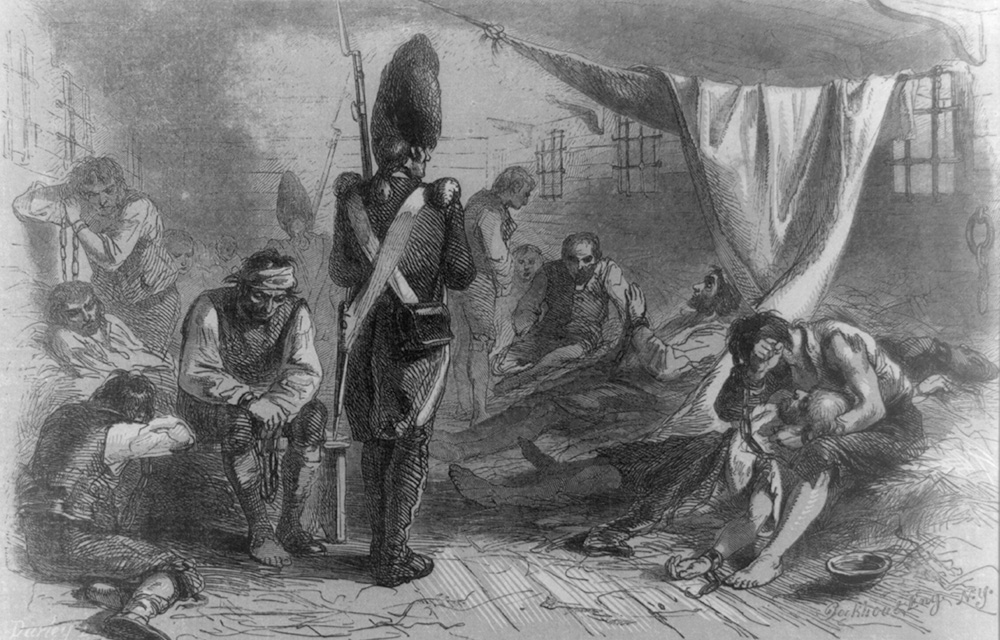

In the face of Forten’s refusal to abandon the patriot cause, Captain Bazely was left with no option but to transfer him to the prison hulk Jersey with the rest of the crew of the captured privateer. The prisoners shared what few resources they had and endured the same misery. Survival outweighed all other considerations. After seven months, James Forten was released in a prisoner exchange. He returned home to discover that his mother and sister had given him up for dead.

In the face of Forten’s refusal to abandon the patriot cause, Captain Bazely was left with no option but to transfer him to the prison hulk Jersey with the rest of the crew of the captured privateer. The prisoners shared what few resources they had and endured the same misery. Survival outweighed all other considerations. After seven months, James Forten was released in a prisoner exchange. He returned home to discover that his mother and sister had given him up for dead.

When the war ended, Forten traveled to England as a common sailor on a trading vessel. Then he came back to Philadelphia, and to a remarkable opportunity. His father’s former employer, Robert Bridges, hired him. Bridges trained Forten, promoted him to foreman, made him his junior partner, introduced him to the shipowners he worked for, and eventually arranged for him to take over the loft. Although Bridges had sons he could have trained in the sailmaker’s trade, he wanted something better for them—at least, better in his mind than working with their hands. He intended them to become merchants or lawyers or doctors. That left the way open for James Forten.

Forten never forgot the faith Robert Bridges had placed in him. He named his second son after him, and helped the Bridges family when various crises befell them. It angered him that few other White employers shared Robert Bridges’s willingness to give someone a chance to prove themselves. Again and again, he lamented the lack of employment opportunities for Black men—especially young Black men—but he refused to do the very thing he criticized others for doing. If someone came to him looking for work, he judged them on aptitude alone.

When James Forten died in March 1842, several thousand Philadelphians turned out to watch his funeral procession pass by. In that crowd were White shipowners and merchants, many of whom had done business with Forten over the years. Much as he would have appreciated their show of respect, he would have appreciated it far more if they had adhered to his belief that America should look like the small, companionable, and race-blind world he had created in his sail loft.

Julie Winch is a professor of history at the University of Massachusetts Boston. She is the author of several books, including Philadelphia’s Black Elite: Activism, Accommodation, and the Struggle for Autonomy, 1787–1848 (Temple University Press, 1988), A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten (Oxford University Press, 2002), which won the American Historical Association’s Wesley Logan Prize, and Between Slavery and Freedom: Free People of Color in America from Settlement to the Civil War (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014).

[1] James Forten, as quoted in “A Noble Example,” Anti-Slavery Record, December 1835.

[2] James Forten, letter to William Lloyd Garrison, February 23, 1831. Rare Books Department, Boston Public Library.