Mary Ellen Pleasant, Freedom-Fighting Entrepreneur

by Lynn M. Hudson

Abolitionist and capitalist Mary Ellen Pleasant does not seem like the obvious choice for a lesson on Black entrepreneurship. Her work as a freedom fighter, boardinghouse keeper, and investor renders her atypical in histories of American entrepreneurs. But Pleasant’s history pushes us to expand our definition of entrepreneurship and for that reason she provides an illuminating case study.

Abolitionist and capitalist Mary Ellen Pleasant does not seem like the obvious choice for a lesson on Black entrepreneurship. Her work as a freedom fighter, boardinghouse keeper, and investor renders her atypical in histories of American entrepreneurs. But Pleasant’s history pushes us to expand our definition of entrepreneurship and for that reason she provides an illuminating case study.

Pleasant’s early history—before arriving in California—is murky. She claimed she was born to free parents in Philadelphia in 1819. Others, including Helen Holdredge, the author of the semi-fictionalized Mammy Pleasant, claimed Pleasant was born enslaved in Georgia.[1] Whether she spent her early years enslaved or free, Pleasant chose to describe her childhood as one spent in freedom. Of course, life in the so-called free states came with its own sets of restrictions and anti-Black practices. In the 1820s Pleasant lived in the abolitionist hotbed of Nantucket, Massachusetts. In her autobiography she explained, “When I was about six years of age, I was sent to Nantucket, Mass., to live with a Quaker woman.”[2] She was soon put to work as a shop clerk, where she began her education in mercantilism. Pleasant would later brag about her ability to bring customers into the shop and “get them to buy things of me.”[3] On the small island she would meet and mingle with sailors, hucksters, and conductors of the Underground Railroad. These contacts—and the skills she developed—would serve her well. Nantucket Town was one of the busiest ports in North America and a center of the whaling trade; it was also overrun with woman-owned shops due to the abundance of so-called whaling wives who ran the town while the men were at sea.[4] It was the ideal place for a girl to learn business.

From Nantucket, Pleasant traveled to Boston, New England’s largest city, where she met her first husband, James Smith. An abolitionist of some means, Smith died in the 1840s leaving Pleasant a generous amount of capital. W. E. B. Du Bois alleged that Pleasant inherited as much as $50,000.[5] She used this money to travel to San Francisco in the early 1850s, at the height of the gold rush.[6] Here, Pleasant’s business acumen was put to good use. Describing her investment strategy when she arrived in the Golden State, she said: “I divided this money among Fred Langford and William West of West & Harper . . . They put my money at ten percent interest and I did an exchange business, sending down gold and having it exchanged for silver.”[7] In addition to her investments, she secured work as a cook and housekeeper in the home of abolitionists that she knew from the east coast. As a free Black woman in San Francisco during the time of the gold rush, Pleasant had few choices for employment. Domestic jobs were one of her only options, like most Black women in the United States. Taking a job as a cook allowed Pleasant to obscure the extent of her wealth. The San Francisco press took to referring to her as “Mammy Pleasant,” a term she disdained, but one that furthered her goal of obscuring her capitalist endeavors.

In addition to her investments, she secured work as a cook and housekeeper in the home of abolitionists that she knew from the east coast. As a free Black woman in San Francisco during the time of the gold rush, Pleasant had few choices for employment. Domestic jobs were one of her only options, like most Black women in the United States. Taking a job as a cook allowed Pleasant to obscure the extent of her wealth. The San Francisco press took to referring to her as “Mammy Pleasant,” a term she disdained, but one that furthered her goal of obscuring her capitalist endeavors.

As Pleasant was establishing her financial empire in California, she worked as a leading agent on the western route of the Underground Railroad, helping fugitives to safety. Her abolitionist networks across the country would serve her well. In twentieth-century interviews, Black San Franciscans revealed that Pleasant was in regular contact with abolitionists from New England. Indeed, these connections and commitments inspired her to travel to Canada and meet with John Brown. Before Brown led his infamous raid on Harpers Ferry, he met with leading abolitionists in Canada to plan his ill-fated attempt to free southern slaves. Although most accounts of the raid mention the support he received from a committee known as the Secret Six, they do not mention Mary Ellen Pleasant, who also supported him. Placing Pleasant among the funders of Brown’s raid makes her central to a pivotal event in the then pending Civil War. Her commitment to the abolition of slavery was not incidental; it was part of her entrepreneurial legacy.

After the Civil War, Pleasant challenged the anti-Black laws and practices that continued to shape the Golden State. Segregated public transportation would be a critical battleground for African Americans in the struggle for civil rights and in 1866 Pleasant became one of the first Black women to fight against Jim Crow streetcars. In that year, she brought complaints against two streetcar companies: Omnibus Railroad Company and the North Beach and Mission Railroad Company [NBMRR]. In the first case, she filed suit against Omnibus for “putting her off the car.”[8] Newspaper coverage of the case indicated that she withdrew her complaint because “she had been informed by the agents of the company that negroes would hereafter be allowed to ride on the car.”[9] In Pleasant’s second suit, against NBMRR, she was awarded $500 damages when the streetcar refused to let her board the car. On appeal, however, the company won. The California Supreme Court ruled in 1868 that there was “no proof . . . to show willful injury.”[10] Nevertheless, Pleasant’s challenge to segregated streetcars was applauded by those across the nation who were pushing back against Jim Crow.

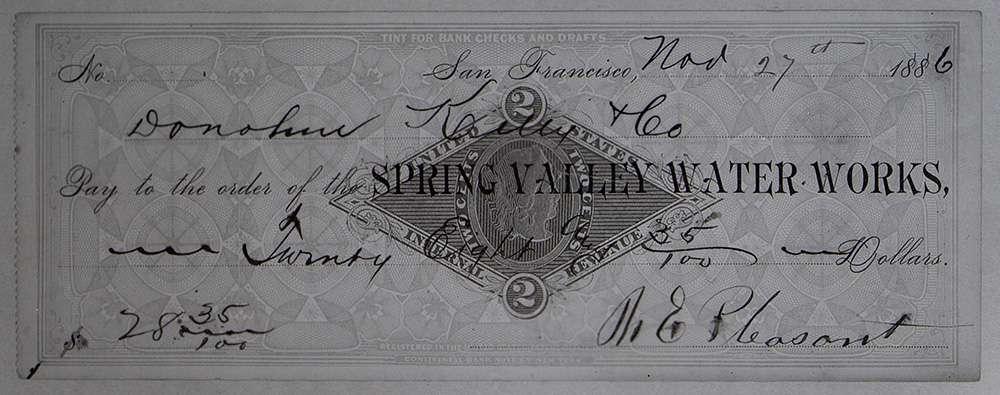

In 1869 Pleasant opened her first boardinghouse in the city, an exclusive establishment frequented by robber barons and railroad tycoons. By the 1880s, she had amassed a sizable empire that included boardinghouses, homes in San Francisco and Oakland, a ranch in Sonoma, and myriad investments in extractive resources. This wealth also made her the target of detractors, creditors, and politicians. She appeared in multiple lawsuits brought by wealthy Californians—many accusing her of fraud, theft, even voodoo—and when she died in 1904, she left behind a fraction of her former wealth. The San Francisco Examiner ran the following headline: “Mammy Pleasant Will Work Weird Spells No More: Mysterious Old Negro Woman, at 89, Ends a Life of Schemes and Varied Fortune.”

In 1869 Pleasant opened her first boardinghouse in the city, an exclusive establishment frequented by robber barons and railroad tycoons. By the 1880s, she had amassed a sizable empire that included boardinghouses, homes in San Francisco and Oakland, a ranch in Sonoma, and myriad investments in extractive resources. This wealth also made her the target of detractors, creditors, and politicians. She appeared in multiple lawsuits brought by wealthy Californians—many accusing her of fraud, theft, even voodoo—and when she died in 1904, she left behind a fraction of her former wealth. The San Francisco Examiner ran the following headline: “Mammy Pleasant Will Work Weird Spells No More: Mysterious Old Negro Woman, at 89, Ends a Life of Schemes and Varied Fortune.”

The history of Black entrepreneurs has been one that often features male inventors, moguls, and executives. It is a history that skews toward the twentieth century in addition to being male dominated. Pleasant’s career, and her willingness to combine freedom fighting with entrepreneurial success, points to a different kind of entrepreneurship, one pioneered by Black women, in particular, that combined capitalist investment with philanthropy. Seeing Pleasant as both an entrepreneur and an abolitionist challenges our assumptions about the legacy of Black entrepreneurs; it pushes us to appreciate the ways African American women shaped histories of abolition and civil rights as they created capitalist empires and traditions of empowerment.

Lynn M. Hudson is a professor of history at the University of Illinois Chicago. She is the author of The Making of “Mammy Pleasant”: A Black Entrepreneur in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco (University of Illinois Press, 2003) and West of Jim Crow: The Fight against California’s Color Line (University of Illinois Press, 2020).

[1] Helen Holdredge, Mammy Pleasant (New York: G. P. Putnam and Sons, 1953): 8.

[2] Mary Ellen Pleasant, “Memoirs and Autobiography,” Pandex of the Press I (January 1902): 5.

[3] Mary Ellen Pleasant, “Memoirs and Autobiography,” Pandex of the Press I (January 1902): 5.

[4] On the female economy of Nantucket, see Lisa Norling, Captain Ahab Had a Wife: New England Women and the Whale Fishery, 1720–1870 (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2000).

[5] W. E. B. DuBois, The Gift of Black Folk: The Negroes in the Making of America (Boston: Stratford, 1924): 271.

[6] Pinpointing Pleasant’s arrival date in San Francisco is difficult. She claimed that she arrived in 1849. Other sources, including African American contemporaries, claimed that she arrived in 1852. Lynn M. Hudson, The Making of ‘Mammy Pleasant’: A Black Entrepreneur in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco (Urbana: Illinois University Press, 2003): 29–30.

[7] Mary Ellen Pleasant, “Autobiographical Segments,” as quoted in Lerone Bennett, “An Historical Detective Story: The Mystery of Mary Ellen Pleasant, Part II,” Ebony (May 1979): 74.

[8] Alta California, October 17, 1866.

[9] Alta California, October 17, 1866.

[10] Pleasants v. NBMRR, California Reports 34, 586 (1868).