"Prince of Darkness": Jeremiah G. Hamilton, Wall Street's First Black Millionaire

by Shane White

Jeremiah G. Hamilton was a Black man whose very existence flies in the face of our understanding of the way things were in nineteenth-century New York. He made his fortune as a broker. Although a pioneer, far from being some novice feeling his way around the economy’s periphery, he was a Wall Street adept, a skilled and innovative financial manipulator. Unlike later Black success stories such as Madam C. J. Walker, the early twentieth-century manufacturer of beauty products, who would make their fortunes selling goods to Black consumers, Hamilton cut a swath through the White New York business world of the middle decades of the nineteenth century. His depredations earned him the nickname “Prince of Darkness.” No matter how challenging it is to accepted views of nineteenth-century New York, Hamilton was a wealthy African American who lived and worked in the city for some forty years.

Jeremiah G. Hamilton was a Black man whose very existence flies in the face of our understanding of the way things were in nineteenth-century New York. He made his fortune as a broker. Although a pioneer, far from being some novice feeling his way around the economy’s periphery, he was a Wall Street adept, a skilled and innovative financial manipulator. Unlike later Black success stories such as Madam C. J. Walker, the early twentieth-century manufacturer of beauty products, who would make their fortunes selling goods to Black consumers, Hamilton cut a swath through the White New York business world of the middle decades of the nineteenth century. His depredations earned him the nickname “Prince of Darkness.” No matter how challenging it is to accepted views of nineteenth-century New York, Hamilton was a wealthy African American who lived and worked in the city for some forty years.

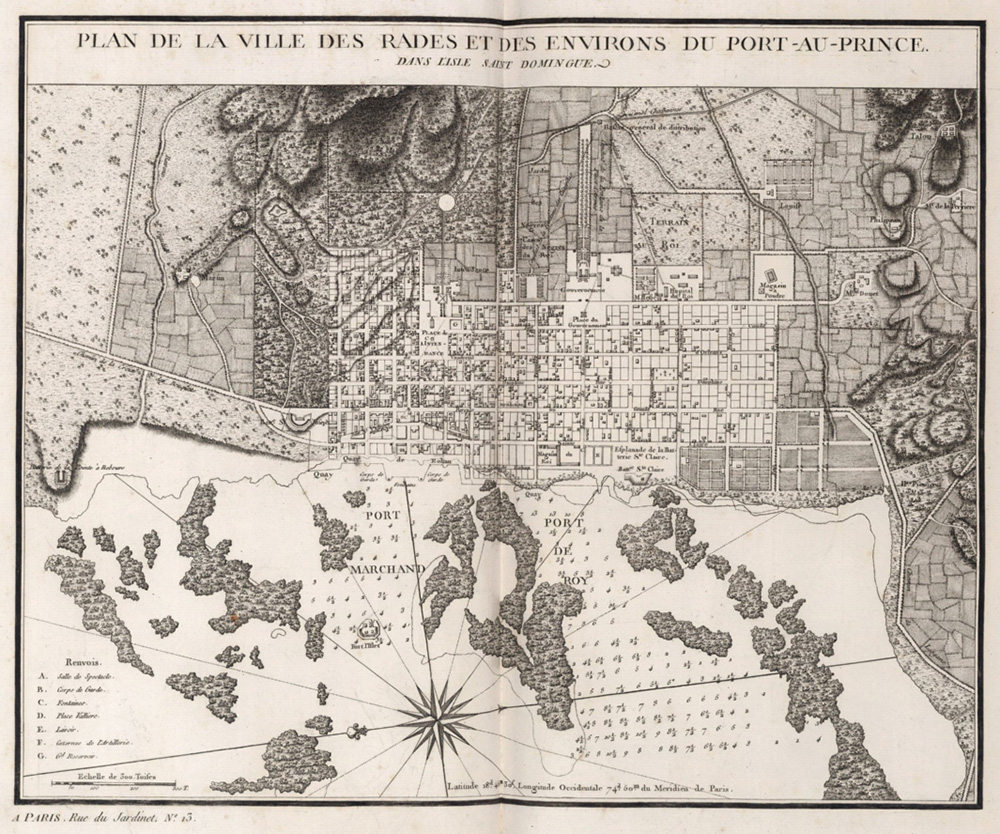

Hamilton was born in 1807, probably in or near Port-au-Prince, Haiti. He first appeared in New York in 1828 as an enterprising twenty-year-old, when he managed to get himself selected as the front man for a consortium of White merchants and businessmen, chartered a brig, and smuggled counterfeit Haitian coin from New York to Port-au-Prince. As it turned out the forged coins were too good—when a bank clerk assayed their silver content, it was higher than that of genuine currency—and the conspiracy unraveled. Tipped off that the game was up, Hamilton dumped as much coin as he could out of a porthole into the harbor and fled just before the arrival at the dock of a captain and six armed soldiers sent to arrest him. Hamilton skulked around Port-au-Prince harbor for twelve days, sheltered by local Black fishermen, before surreptitiously boarding a New York–bound vessel and escaping. A Haitian court sentenced Hamilton, in absentia, to be shot summarily if he was caught anywhere in the country.[1] He never returned to Haiti.

Soon after, Hamilton moved permanently to New York. For much of the first half of the 1830s he struggled to gain a foothold as a broker in the city’s lily-white financial world. A trail of lawsuits over debts documented his difficulties. There was a frenetic, almost desperate quality to the way Hamilton borrowed money in these years. He postponed paying debts as long as possible, usually way past the due date, never panicked, and kept on sweet-talking new prospects. Hamilton resembled nothing so much as a hustler working at an upturned wooden crate on the sidewalk, moving his shells and never letting the mark know under which one he has secreted the money. Several irritated creditors certainly were convinced that something akin to a shell game was going on and that he was hiding assets. Hamilton, though, kept his nerve and, in much the same fashion as a talented three-card monte player, came out a winner. Unlike a three-card monte player, though, Hamilton was working the big end of town, not the street.

Hamilton had a reputation for insuring vessels which then mysteriously sank, developing a fraught relationship with every marine insurance company. The nascent business had begun to organize itself in the 1820s; in 1832 nine companies founded the Board of Underwriters of New York to regulate the industry. By 1835 Hamilton had claims of as much as three thousand dollars against at least three of the board’s nine founding firms. Chances are that he was scamming the insurance companies—his victims certainly squealed loudly in court that that was the case. New York insurance companies imposed a ban on Hamilton. As a writer in the New York Spectator reported, “the offices in this city have resolved among themselves not to insure” any of his business ventures.[2] This was no impediment for Hamilton. In 1835, by subterfuge involving a proxy, he insured the Meridian for $12,000. Unhappily, a storm wrecked the brig off the Charleston bar. Although the rightly suspicious insurance company unsurprisingly refused to honor the policy, the court instructed it to pay the $12,000 as well as $620 interest and costs. There was often a taint to Hamilton’s methods, but his footwork as he insured the Meridian was impressively creative, devastatingly effective, and according to a Superior Court judge, perfectly legal.[3]

By the mid-1830s, through a mixture of chicanery and outright fraud, Hamilton had amassed more than $25,000. He had well and truly arrived. In 1836, a cashed-up Jeremiah Hamilton was casting around for investment opportunities and, like almost everyone else in the United States, he was mesmerized by the real estate market. He plunged into the boom buying tracts of land in modern-day Astoria and Poughkeepsie. His extensive holdings in the latter included a four-hundred-foot dock with three storehouses as well as the “splendid dwelling” known as the Mansion House. Hamilton was betting on the property market continuing to boom and betting big, to the tune of more than $10 million in today’s dollars.

But, of course, it didn’t last. He’d bought at the top of the market, only weeks before the crash in the second quarter of 1837 and the onset of a depression that would linger until the 1840s. Hamilton fended off his creditors for years, but in 1841 Congress, desperate to do something about the thousands of failed financiers, merchants, shopkeepers, and artisans languishing throughout the nation, passed an experimental bankruptcy law extraordinarily generous to debtors. On the fourth day of its operation in February 1842, Hamilton registered, and a couple of months later all the money he owed creditors was discharged or written off. He demonstrated a remarkable adroitness and knowledge of how the system worked and could be exploited.[4]

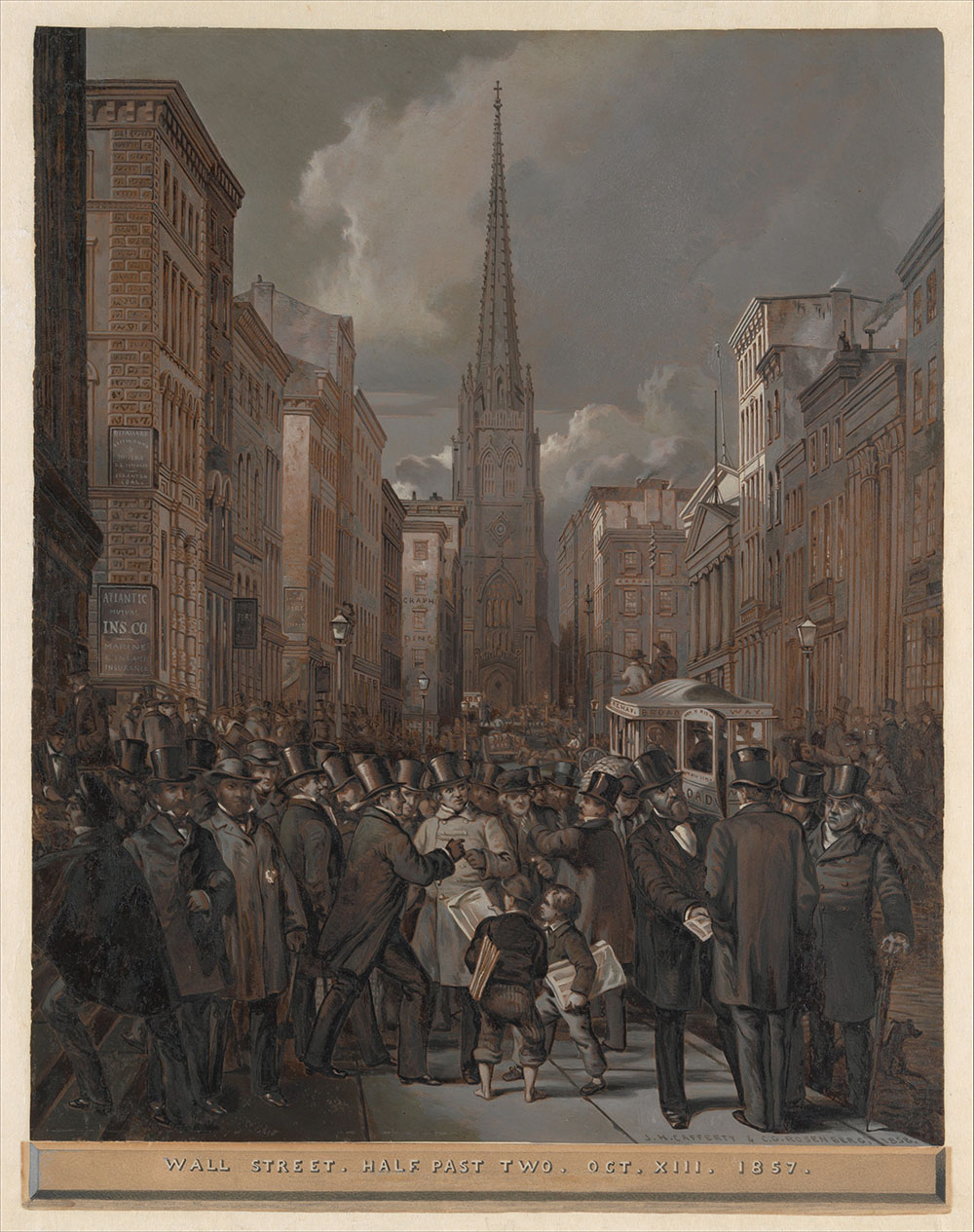

For decades in the middle of the nineteenth century, Jeremiah Hamilton was a Wall Street habitué, actively participating in the share market. It was here in the crucible of American capitalism that he re-established himself after bankruptcy. He had many memorable ventures. In the 1850s, he clashed with Cornelius Vanderbilt, famed as America’s first tycoon, in a stock market brawl over control of a company pioneering a route through Nicaragua to the Pacific Ocean. After Vanderbilt’s death a front-page obituary in the National Republican recorded: “There was only one man who ever fought the Commodore to the end, and that was Jeremiah Hamilton.” Vanderbilt named only one opponent whom he “respected” in a takeover battle, although “he did not fear” Hamilton “because he never feared anybody.”[5] In the 1860s, if not before, Hamilton was running a “pool,” like a modern hedge fund. Investors contributed money that would be used as the margin, or security, to borrow more money. This leveraging allowed Hamilton to take more aggressive positions in particular stocks and shares, making more money in any bull market. A few White men were willing almost to grovel, gifting Hamilton cigars and champagne, to gain access to this African American’s wisdom about the prospects of listed corporations, especially those laying thousands of miles of railroad track and steaming huge iron vessels across oceans. The remarkable detail here is that Hamilton as a Black man would have been shunned as a customer by the corporations whose stocks he was recommending.

For decades in the middle of the nineteenth century, Jeremiah Hamilton was a Wall Street habitué, actively participating in the share market. It was here in the crucible of American capitalism that he re-established himself after bankruptcy. He had many memorable ventures. In the 1850s, he clashed with Cornelius Vanderbilt, famed as America’s first tycoon, in a stock market brawl over control of a company pioneering a route through Nicaragua to the Pacific Ocean. After Vanderbilt’s death a front-page obituary in the National Republican recorded: “There was only one man who ever fought the Commodore to the end, and that was Jeremiah Hamilton.” Vanderbilt named only one opponent whom he “respected” in a takeover battle, although “he did not fear” Hamilton “because he never feared anybody.”[5] In the 1860s, if not before, Hamilton was running a “pool,” like a modern hedge fund. Investors contributed money that would be used as the margin, or security, to borrow more money. This leveraging allowed Hamilton to take more aggressive positions in particular stocks and shares, making more money in any bull market. A few White men were willing almost to grovel, gifting Hamilton cigars and champagne, to gain access to this African American’s wisdom about the prospects of listed corporations, especially those laying thousands of miles of railroad track and steaming huge iron vessels across oceans. The remarkable detail here is that Hamilton as a Black man would have been shunned as a customer by the corporations whose stocks he was recommending.

There was a startling disjuncture between the financial world, where the Black broker was, to borrow from Tom Wolfe, a Master of the Universe, and his everyday existence on the streets of New York where violence erupted easily. This threat was exacerbated by the fact that he married a much younger White woman. During the Draft Riot of 1863 a mob came to their house on East 29th Street with the intention of hanging him from a lamp post. No fool, Hamilton had slipped away over the back fence. His was an impossibly fraught existence.[6]

Hamilton was still dogged by suggestions of fraud, insinuations that any profits he secured were for himself. But gradually he became more respectable. After he died on May 19, 1875, obituaries hinted at the almost establishment-like stature of his final years. According to a Herald writer, “his advise was regarded by some of the most substantial men on the street as exceptionally sound,” a verdict echoed in the Tribune where it was reported his judgment was esteemed and “he was often consulted by prominent bankers.” Dozens of newspapers from one end of the country to the other printed brief notices of his death, often captioned “The Richest Colored Man in the Country,” or some such. According to another, he had “accumulated a colossal fortune of nearly two millions ($2,000,000) dollars.”[7]

Jeremiah Hamilton was forgotten quickly—he never has fitted into the familiar American story. His name was mentioned in print only four times in the twentieth century, and three of those mentions were mistaken or misleading. Now, however, well-known Hollywood figures Don Cheadle and Steven Soderbergh have optioned his story and intend to make a series about him—perhaps at last Jeremiah Hamilton will garner the attention such a remarkable man deserves.[8]

Shane White is a professor emeritus of history at the University of Sydney. He is the author of several books, including Stories of Freedom in Black New York (Harvard University Press, 2002) and Prince of Darkness: The Untold Story of Jeremiah G. Hamilton, Wall Street’s First Black Millionaire (St. Martin’s Press, 2015).

[1] I have written at length about Hamilton. See Shane White, Prince of Darkness: The Untold Story of Jeremiah G. Hamilton, Wall Street’s First Black Millionaire (New York: St Martin’s Press, 2015), 15–35.

[2] New York Spectator, October 24, 1836.

[3] White, Prince of Darkness, 56–58.

[4] White, Prince of Darkness, 129–171.

[5] National Republican, January 5, 1877.

[6] White, Prince of Darkness, 294–303.

[7] New York Herald, May 20, 1875; New York Daily Tribune, May 22, 1875; Philadelphia Inquirer, May 20, 1875; Pacific Appeal, July 31, 1875.

[8] Joe Otterson, “HBO Max to Develop Series About ‘Wall Street’s First Black Millionaire,’ Don Cheadle and Steven Soderbergh Producing (EXCLUSIVE),” Variety, January 13, 2022.