Madam C. J. Walker: A Life of Reinvention

by Erica J. Ball

Nothing about Madam C. J. Walker’s origins would suggest that she would become the most famous Black businesswoman and philanthropist of her day. Indeed, for most of her life, the woman known as Madam C. J. Walker lived in fairly unremarkable circumstances. Born on a cotton plantation in northeastern Louisiana just two years after the end of the Civil War, she spent most of her life eking out a living at the bottom of the economic ladder. And yet, by the time of her death, the girl born into a family of recently emancipated slaves had transformed herself into the head of a successful corporation with an international reputation and amassed an estate valued at somewhere between one half to one million dollars. According to the official press release issued by her eponymous Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, Madam C. J. Walker was nothing less than “the richest colored woman in the world, and the greatest colored philanthropist” in 1919. She was the first American woman of any race to parlay a business venture into such astounding financial success. It is for good reason, then, that Madam C. J. Walker holds a special place in the history of African American entrepreneurship. Hers was a life of extraordinary reinvention, one that spoke directly to the experiences and aspirations of early twentieth-century Black Americans.

Nothing about Madam C. J. Walker’s origins would suggest that she would become the most famous Black businesswoman and philanthropist of her day. Indeed, for most of her life, the woman known as Madam C. J. Walker lived in fairly unremarkable circumstances. Born on a cotton plantation in northeastern Louisiana just two years after the end of the Civil War, she spent most of her life eking out a living at the bottom of the economic ladder. And yet, by the time of her death, the girl born into a family of recently emancipated slaves had transformed herself into the head of a successful corporation with an international reputation and amassed an estate valued at somewhere between one half to one million dollars. According to the official press release issued by her eponymous Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, Madam C. J. Walker was nothing less than “the richest colored woman in the world, and the greatest colored philanthropist” in 1919. She was the first American woman of any race to parlay a business venture into such astounding financial success. It is for good reason, then, that Madam C. J. Walker holds a special place in the history of African American entrepreneurship. Hers was a life of extraordinary reinvention, one that spoke directly to the experiences and aspirations of early twentieth-century Black Americans.

For most of her life, Madam C. J. Walker was known as Sarah, the name bestowed on her by her parents, Owen and Minerva Breedlove. The fifth child in a growing family of tenant farmers, Sarah Breedlove spent her earliest years in the cotton fields of Delta, Louisiana. After the death of her parents, Sarah Breedlove followed the lead of her older siblings and migrated to Mississippi in 1877, settling in the small city of Vicksburg. Still a girl by any measure, Sarah Breedlove had to grow up quickly. Indeed, she became a young wife, a mother, and a widow in rapid succession. As she would later succinctly put it when recounting this time of her life, “I was orphaned at seven, married at fourteen, a widow at twenty.”

After arriving in Vicksburg, Sarah and her older sister Louvenia entered the wage labor economy at the bottom rung, working as laundresses. Given its low pay and physically demanding nature, the laundry trade remained, in many respects, the least desirable form of employment for southern Black women. At the same time, however, the opportunity to have “clients” rather than “employers” and to work either at home or in the company of other Black women offered the possibility for Black laundresses to feel somewhat more independent than the cooks, child-nurses, and maids who spent their days working under constant oversight in White households. By entering the laundry trade, Sarah and Louvenia learned how to style themselves as independent artisans, contractors, or entrepreneurs and to advertise and market their business in the public square. Moreover, by working in concert with other Black women, they learned about the power and significance of Black women’s community. This wasn’t traditional schooling by any means. But it did serve as an important educational experience and as political training for Sarah Breedlove. Indeed, it undoubtedly provided an important foundation for her to build upon years later as she transformed herself into Madam C. J. Walker.

Sometime around 1888 Sarah and her young daughter Lelia migrated to St. Louis, Missouri. She settled into the city’s burgeoning Black community, briefly remarried (and separated), and continued to work as a domestic servant and laundress. But it is here where Sarah Breedlove’s life took a remarkable turn. In St. Louis, Sarah met Mrs. Annie Pope, another recent transplant to the city. A beauty culturist and entrepreneur, Mrs. Pope developed a hair care product that she called “Wonderful Hair Grower” and marketed to other African American women. Sometime around 1903, Sarah received a treatment from Mrs. Pope and subsequently joined the team of sales agents selling Pope’s hair care product to the Black women of their communities. Sarah must have been an exceptional sales agent, for in 1905, she found herself heading to Denver to introduce Pope’s hair care product to the African American communities of the mountain west.

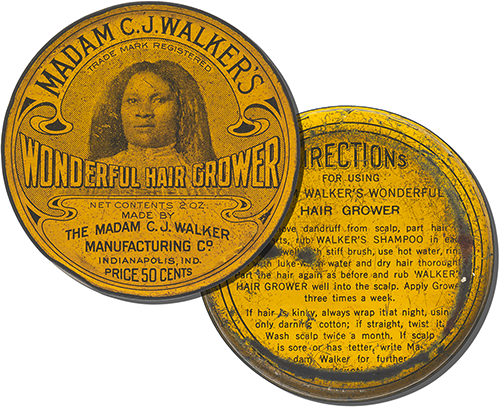

Now in her late thirties, Sarah began taking a series of decisive steps that would alter the trajectory of her life. After marrying her fiancé Charles Walker, she took on a new name and a new professional identity. With the title “Madam” signifying women’s knowledge and authority, Madam C. J. Walker opened a salon of her own, and developed her own product (Madam C. J. Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower), which she began selling in Denver and the surrounding communities. Officially breaking ties with Annie Pope (who would soon trademark her product under the name Poro and go on to build a beauty empire of her own), Madam Walker then embarked on a whirlwind sales campaign, traveling from community to community to demonstrate her products and secure orders that her daughter Lelia would fulfill and distribute by mail from their home in Denver.

Over the next fifteen years, Madam Walker transformed this small business into an international sensation. Tapping into a national climate with modern beauty culture ascendant and a growing number of Black women seeking to style themselves as modern, twentieth-century urban women, Madam Walker and her growing number of agents leaned into Black women’s community networks and associations as they went door to door demonstrating, marketing, and selling Madam C. J. Walker’s hair care products. Her endeavor proved to be wildly successful, for by 1911, Madam Walker was the head of the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, a corporation that sold a growing line of hair care products to a rapidly expanding national customer base. She built a factory in Indianapolis, Indiana, recruited thousands of Black women to work as sales agents, and offered training programs for her “Walker method” to Black beauty culturists across the country. A generous donor to a variety of early civil rights causes and African American institutions, Madam Walker also garnered a reputation as the leading Black philanthropist of the era. As a profile published in the Kansas City Star in 1917 explained to readers, “Madam Walker is the only negro woman on earth who ever gave $1,000 to the Y.M.C.A., and she maintains, year after year, six students at Tuskegee, Ala., paying all their expenses. She lives in luxury, but is not a profligate, giving to the poor what many white folks of her income devote to riotous living.” The article noted that “she has an income of one-quarter of a million dollars a year. She made every cent of her money without aid or encouragement from any living soul. Pause while you take off your hat to her.”

Over the next fifteen years, Madam Walker transformed this small business into an international sensation. Tapping into a national climate with modern beauty culture ascendant and a growing number of Black women seeking to style themselves as modern, twentieth-century urban women, Madam Walker and her growing number of agents leaned into Black women’s community networks and associations as they went door to door demonstrating, marketing, and selling Madam C. J. Walker’s hair care products. Her endeavor proved to be wildly successful, for by 1911, Madam Walker was the head of the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, a corporation that sold a growing line of hair care products to a rapidly expanding national customer base. She built a factory in Indianapolis, Indiana, recruited thousands of Black women to work as sales agents, and offered training programs for her “Walker method” to Black beauty culturists across the country. A generous donor to a variety of early civil rights causes and African American institutions, Madam Walker also garnered a reputation as the leading Black philanthropist of the era. As a profile published in the Kansas City Star in 1917 explained to readers, “Madam Walker is the only negro woman on earth who ever gave $1,000 to the Y.M.C.A., and she maintains, year after year, six students at Tuskegee, Ala., paying all their expenses. She lives in luxury, but is not a profligate, giving to the poor what many white folks of her income devote to riotous living.” The article noted that “she has an income of one-quarter of a million dollars a year. She made every cent of her money without aid or encouragement from any living soul. Pause while you take off your hat to her.”

In the last two years of her life, Madam Walker resided in an elegant mansion on the outskirts of New York City in Irvington-on-Hudson, both geographically and metaphorically miles away from the slave cabin of her birth. She seemed to be fully aware of the extraordinary nature of her transformation in circumstances. As she told the New York Times in 1917, “When, a little more than twelve years ago, I was a washerwoman, I was considered a good washerwoman and laundress. I am proud of that fact. At times I also did cooking, but, work as I would, I seldom could make more than $1.50 a day. I got my start by giving myself a start. It is often the best way.”

This is perhaps why Madam C. J. Walker’s story continues to resonate in the twenty-first century. Her rags-to-riches tale exemplifies the trajectory of the most successful American captains of industry at the turn of the twentieth century. But unlike the Rockefellers and Carnegies of the era, Madam Walker drew upon the experiences of African American women and remained grounded in the practices of African American networks and community.

Selected Bibliography

Baldwin, Davarian L. “From the Washtub to the World: Madam C. J. Walker and the ‘Re-creation’ of Race Womanhood, 1900–1935.” In The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization, eds. Alys Eve Weinbaum et. al. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008, 55–76.

Bundles, A’Lelia. On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker. New York: Washington Square Press, 2001.

Chapman, Erin D. Prove it On Me: New Negroes, Sex, and Popular Culture in the 1920s. New York. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Freeman, Tyrone McKinley. Madam C. J. Walker’s Gospel of Giving: Black Women’s Philanthropy During Jim Crow. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020.

Gill, Tiffany M. Beauty Shop Politics: African American Women’s Activism in the Beauty Industry. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010.

Lowry, Beverly. Her Dream of Dreams: The Rise and Triumph of Madam C. J. Walker. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003.

Peiss, Kathy. Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture. New York: Metropolitan Books, 1998.

Rooks, Noliwe M. Hair Raising: Beauty, Culture, and African American Women. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1996.

Walker, Susannah. Style and Status: Selling Beauty to African American Women, 1920–1975. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2007.

Erica Ball is a professor of Black studies at Occidental College. She is the author of To Live an Antislavery Life: Personal Politics and the Antebellum Black Middle Class (University of Georgia Press, 2012) and Madam C. J. Walker: The Making of an American Icon (Rowman & Littlefield, 2021) and the editor, with Tatiana Seijas and Terri L. Snyder, of As If She Were Free: A Collective Biography of Women and Emancipation in the Americas (Cambridge University Press, 2020).