The Religious Diversity of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence

by Richard Carwardine

The Declaration of Independence was more than a founding political document of an embryonic American nation. It was also a moral summons to united action written and signed by fifty-six men of diverse religious views. The document declared God’s sanction for colonial separation from Britain. It made no mention of Christianity. But take a close look and you will find a sprinkling of clues that reveal the range and force of the religious faiths that lay behind it. Although the text is commonly regarded as Thomas Jefferson’s handiwork—reasonably so, since he was the chief author—it emerged from a committee of five that left most of the drafting task to him, and took its final form only after some revision by members of the Second Continental Congress.[1]

In its preamble, the Declaration asserts that the political independence of the thirteen states—their “separate and equal station” as a power on earth—was sanctioned by “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.” It was a self-evident truth “that all men are created equal . . . endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights,” including “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”[2]

Here, in Jefferson’s understanding, was the creator God, a deity consistent with eighteenth-century rationalist ideas, the thought streams of science and philosophy that fed the Enlightenment. The sage of Monticello, in common with other Deists of the American founding generation, questioned the divine inspiration of the Bible and dismissed the “demoralizing dogmas of Calvin” as a “counter-religion made up of the deliria of crazy imaginations.”[3] Two members of the committee offered minor amendments to Jefferson’s text, none of them material. These were John Adams, a Calvinist Congregationalist turned Unitarian, and the equally unorthodox Benjamin Franklin, a Freemason devoted to the ideal of human progress.[4] They shared with Jefferson a lifelong interest in religion and his esteem for Christianity’s ethical principles. Together they ensured the Declaration was grounded in righteousness and virtue. Jefferson’s original draft began: “We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable.” The final text concluded with the signers’ pledge to each other, and to their revolutionary project, of “our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.”

At the same time, the Declaration in its final form spoke of God in terms consistent with orthodox Holy Scripture. The signers appealed “to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions.” They made their pledges “with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence.” These additions to Jefferson’s original draft resulted from the debates in Congress, which Adams led, and indicate the intervention of orthodox Christians.

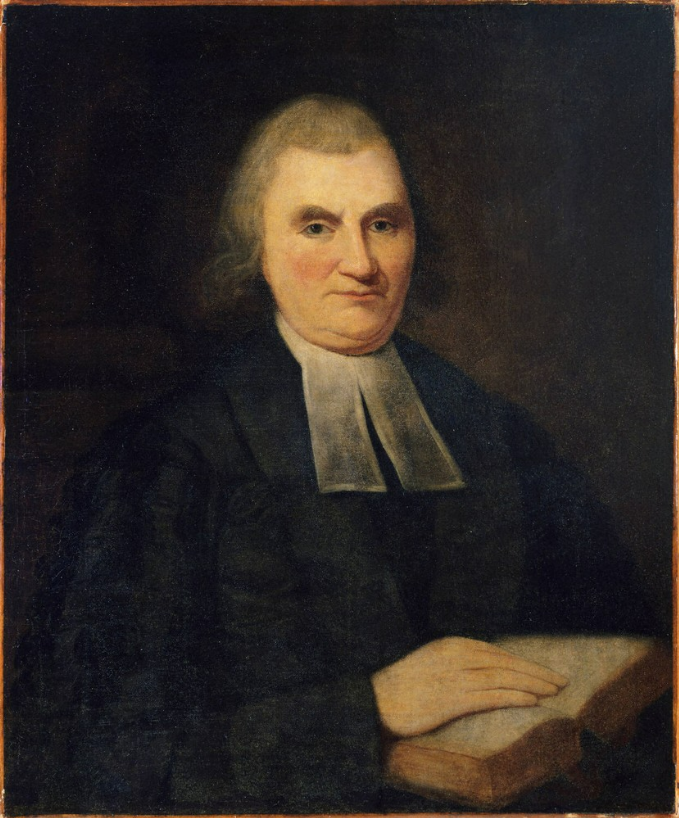

There the stand-out Christian figure was John Witherspoon, president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University), the only minister in the Congress, and one of some dozen signers of the Declaration whose lives had been shaped by Presbyterianism. Two of these—Richard Stockton, one of the college’s trustees, and the distinguished physician Dr. Benjamin Rush—had persuaded Witherspoon to leave his ministry in Scotland in 1768 and take on the role of “revered . . . Head of Presbyterian Interest . . . dayly growing in these Middle Colonies.” A proponent of Scottish Common Sense philosophy, Witherspoon gave unshakeable support to the movement for independence, sure that human rights flowed from God’s authority, not monarchical power, and that political and religious freedom were inseparably connected.[5]

There the stand-out Christian figure was John Witherspoon, president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University), the only minister in the Congress, and one of some dozen signers of the Declaration whose lives had been shaped by Presbyterianism. Two of these—Richard Stockton, one of the college’s trustees, and the distinguished physician Dr. Benjamin Rush—had persuaded Witherspoon to leave his ministry in Scotland in 1768 and take on the role of “revered . . . Head of Presbyterian Interest . . . dayly growing in these Middle Colonies.” A proponent of Scottish Common Sense philosophy, Witherspoon gave unshakeable support to the movement for independence, sure that human rights flowed from God’s authority, not monarchical power, and that political and religious freedom were inseparably connected.[5]

There was nothing in the terms “Nature’s God” or “Creator” that would in themselves have troubled Witherspoon and other Trinitarian Christians. God worked through the forces of Nature that he had created. But Witherspoon and his evangelical wing of Protestantism rejected the notion of a Prime Mover who had withdrawn from the world that he had made so that his clockwork creation should run itself. The evangelicals’ Almighty was an active God who judged humankind and intervened in human affairs. He protected or punished His people according to their deserts.[6]

The Continental Congress that drafted the Declaration was a microcosm of the wider religious landscape. On the cusp of nationhood, the American colonies’ churches were more diverse than anywhere in the Old World. Religious revivals and immigration had produced an astonishing array of spiritual groups. That diversity weakened the grip of established churches and their claim to special privilege. Baptists, Quakers, and Anglicans challenged Congregationalist hegemony in New England. The Anglican establishment in Virginia met the defiance of New Light Baptists and Presbyterians. A striking ethnic mix in the middle and southern colonies nurtured Roman Catholic churches, as well as communities of German Lutherans, Mennonites, Moravians, French Huguenots, Dutch Reformers, Sephardic Jews, and Scottish and Scots Irish traditions.[7]

Most of those who gathered in Philadelphia were for the first time engaging face to face with representatives of that rich religious pluralism. Unitarians, Presbyterians, and Anglicans rubbed shoulders with those of Quaker background like Joseph Hewes of North Carolina, and Baptist farmer-politicians like John Hart of New Jersey.[8] The Catholic Church was present, too, through the lone figure of the Jesuit-educated Charles Carroll of Maryland, whose vast Carrollton estates and slave-holding interests made him possibly the wealthiest man in the colonies. The multiplicity of traditions had the effect of concentrating minds on what united them: independence from Britain.

Most of those who gathered in Philadelphia were for the first time engaging face to face with representatives of that rich religious pluralism. Unitarians, Presbyterians, and Anglicans rubbed shoulders with those of Quaker background like Joseph Hewes of North Carolina, and Baptist farmer-politicians like John Hart of New Jersey.[8] The Catholic Church was present, too, through the lone figure of the Jesuit-educated Charles Carroll of Maryland, whose vast Carrollton estates and slave-holding interests made him possibly the wealthiest man in the colonies. The multiplicity of traditions had the effect of concentrating minds on what united them: independence from Britain.

Consensual pragmatism may account for the absence of any overt reference to religion in the Declaration’s list of twenty-eight specific grievances against George III. One omission is especially noteworthy. The threat that the king might appoint an Anglican bishop in the colonies had fed resistance during the 1760s and 1770s. John Adams later claimed that “the apprehension of Episcopacy” contributed as much anything to the coming of revolution.[9] But this particular concern about religious liberty is missing from the Declaration, probably because the fractious question of religious establishments was a divisive issue for colonial churches.

One grievance alone in the Declaration’s list pertained to religion, though not directly by name. The king and parliament were censured “For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government.” The Quebec Act of 1774 had extended that Catholic province’s boundaries, guaranteed the free practice of the Catholic faith, and restored the French civil law for private matters. The thirteen overwhelmingly Protestant colonies raged against another “Intolerable Act.” Why then did a Catholic, Charles Carroll, sign a document denouncing a British measure that protected his own faith? Because, as he later explained, “I had in view not only our independence of England, but the toleration of all sects professing the Christian religion and communicating to them all equal rights.”[10]

One grievance alone in the Declaration’s list pertained to religion, though not directly by name. The king and parliament were censured “For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government.” The Quebec Act of 1774 had extended that Catholic province’s boundaries, guaranteed the free practice of the Catholic faith, and restored the French civil law for private matters. The thirteen overwhelmingly Protestant colonies raged against another “Intolerable Act.” Why then did a Catholic, Charles Carroll, sign a document denouncing a British measure that protected his own faith? Because, as he later explained, “I had in view not only our independence of England, but the toleration of all sects professing the Christian religion and communicating to them all equal rights.”[10]

Jefferson’s religious pragmatism matched Carroll’s. For example, when the British had prepared to shut down the port of Boston in 1774, he led a move in Virginia “to call up & alarm” the people and arouse them “from the lethargy into which they had fallen.” No Puritan himself, he was prepared to act like one. He consulted the works of an English Civil War Roundhead, John Rushworth, and “rummaged . . . for the revolutionary precedents & forms of the Puritans of that day . . . [and] cooked up a resolution . . . for a day of fasting, humiliation & prayer, to implore heaven to avert from us the evils of civil war, to inspire us with firmness in support of our rights.”[11]

That same religious pragmatism in the pursuit of continental unity led Jefferson and his committee to embrace Congress’s additions to his original draft of the Declaration. The theistic premise of the final document, that the earthly world is ruled by God, allowed all the signatories—whether leaning towards Deism or Christianity, rationalism or biblicism—to unite in their diversity behind a natural rights manifesto that would shake the world.

Richard Carwardine is Emeritus Rhodes Professor of American History at Corpus Christi College, the University of Oxford. His many books include Evangelicals and Politics in Antebellum America (Yale University Press, 1993), Lincoln: A Life of Purpose and Power (Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), The Global Lincoln , co-edited with Jay Sexton (Oxford University Press, 2011), and Lincoln’s Sense of Humor (Southern Illinois University Press, 2017).

[1] Matthew L. Harris and Thomas S. Kidd, eds., “Religion and the Continental Congress,”

in Matthew L. Harris and Thomas S. Kidd, eds., The Founding Fathers and the Debate over Religion in Revolutionary America: A History in Documents (2011; online ed., Oxford Academic, Jan. 19, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195326499.003.0001 , accessed Oct. 8, 2022.

[2] For the text of Jefferson’s “original Rough draught” and the Declaration as adopted by Congress, see: https://jeffersonpapers.princeton.edu/selected-documents/declaration-independence .

[3]Thomas Jefferson Randolph, ed., Memoirs, Correspondence, and Private Papers of Thomas Jefferson , vol. 4 (London, 1829), 357–358.

[4] Steven Waldman, Founding Faith: Providence, Politics, and the Birth of Religious Freedom in America (New York: Random House, 2008); David L. Holmes, The Faiths of the Founding Fathers (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2006).

[5] William B. Miller, “Presbyterian Signers of the Declaration of Independence,” Journal of the Presbyterian Historical Society 36 (September 1958), 139–179.

[6] Nicholas Guyatt, Providence and the Invention of the United States, 1607–1876 (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 95–133.

[7] Jon Butler, Becoming America: The Revolution before 1776 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), 185–224.

[8] For more on the Quaker Joseph Hewes and the Baptist John Hart, see https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/declaration/bio18.htm and Hight C. Moore, “The Baptists and the American Revolution,” Peabody Journal of Education 23 (July 1945), 51.

[9] Patricia U. Bonomi, Under the Cope of Heaven: Religion, Society, and Politics in Colonial America (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 200.

[10] Waldman, Founding Faith, 91.

[11] “Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on Early Career (the so-called ‘Autobiography’)” [6 January–29 July 1821], 313. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, digital edition.