Pledging Their Fortunes: The Professions of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence

by Denver Brunsman

Within the historical literature, the professions of the fifty-six signers of the Declaration of Independence has not received nearly the same attention paid to the framers of the US Constitution. In his Economic Interpretation of the Constitution (1913), Charles A. Beard famously argued that personal financial interests largely motivated the national government plan. Historians have challenged the interpretation for generations, citing both a diversity of economic interests that Beard did not account for and deeper ideological motivations among the framers. At the same time, few scholars today question that the privileged economic status of the White men who drafted the Constitution had at least some influence on the document.[1]

The same is not true for the Declaration of Independence. Even though the economic status and professions of the signers of the Declaration nearly mirrored those of the framers of the Constitution (in fact, six men signed both documents), there is no equivalent of Beard, no “Economic Interpretation of the Declaration of Independence.” There is a significant reason. Although the elite status of the signers, as well as their professional diversity, helped to ensure the success of the Declaration, it is much harder to argue that economics drove the decision for American independence. To the contrary, the delegates to the Second Continental Congress put themselves at serious financial risk by serving in the body and declaring independence. When the signers pledged their fortunes, along with their lives and sacred honor, in the final lines of the Declaration, it was more than a stirring close. It was true.

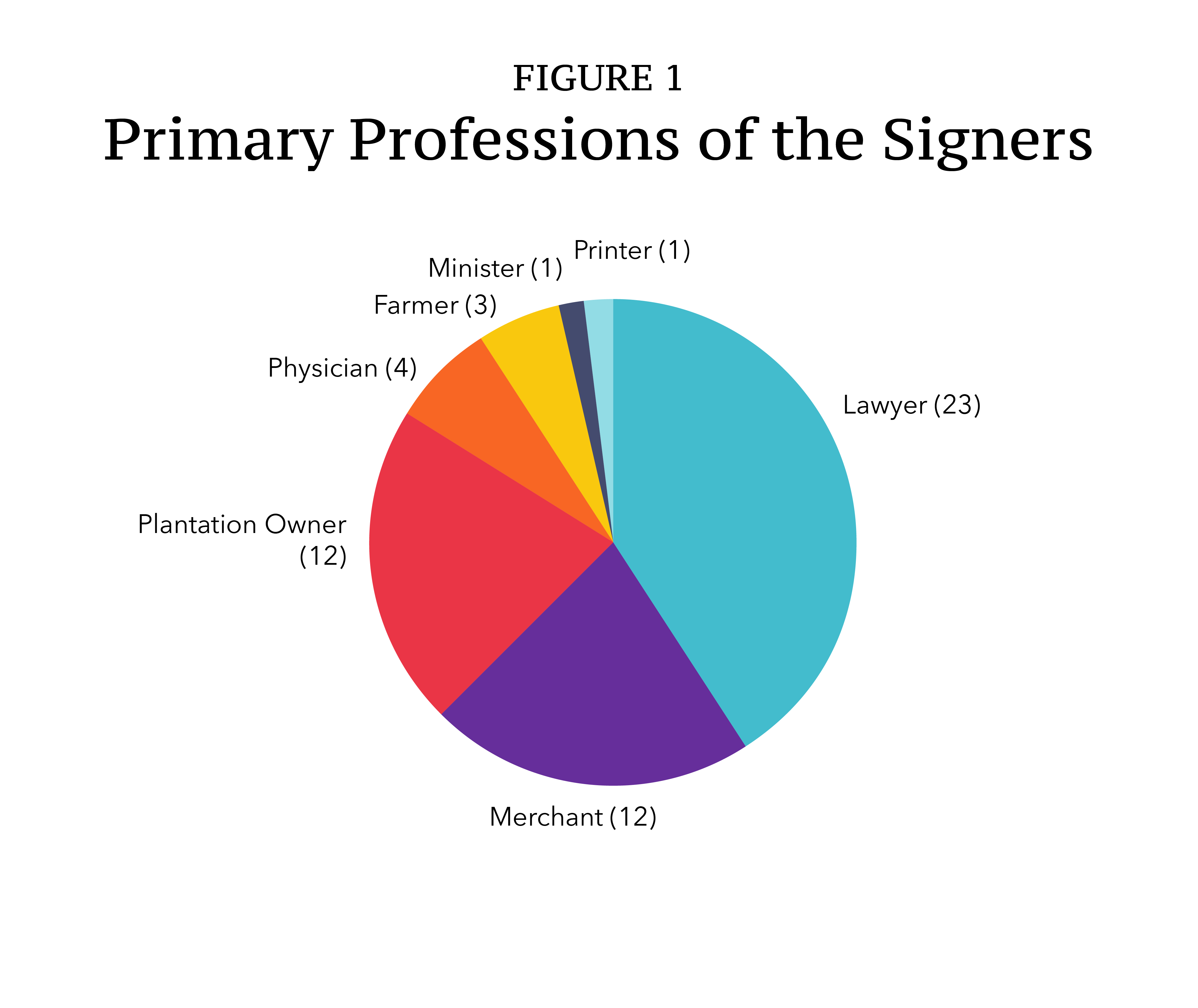

On one level, the professions of the signers mattered because their elite status helped to command authority. Many signers engaged in multiple economic pursuits, but by identifying how individuals primarily gained their wealth, three professions stand out: lawyer, merchant, and plantation owner (Figure 1). Twenty-three of the fifty-six signers (41 percent) earned their living primarily by practicing law, making it the most common profession. This figure does not include several trained lawyers, such as Thomas Jefferson, who depended more on other income sources (in Jefferson’s case, his plantation). By contrast, William Paca of Maryland was a lawyer first and plantation owner second, ultimately rising in the legal profession to become an early federal district judge.[2]

The next most common professions were merchant and plantation owner, with twelve individuals respectively among the signers (21 percent each). Again, several men could claim both professions, but in most cases the men gained wealth first from their plantations. For example, Charles Carroll of Carrollton’s merchant activities flowed naturally from his massive landowning, enough to make him the wealthiest member of Congress and quite possibly in all of the thirteen rebelling American colonies. Yet not every signer was Charles Carroll. The English-born Button Gwinnett of Georgia was a merchant and a planter, not a merchant planter, and was not very successful at either business. Other merchants, such as Robert Morris, engaged in land speculation (as did many of the signers), but he made the bulk of his fortune from trade and finance before losing it after the American Revolution. A handful of merchants, all from the northern colonies, followed the economic profile of John Hancock, the president of Congress at the time of independence, in making their fortunes primarily through shipping and trade.

After lawyer, merchant, and plantation owner, the signers pursued a handful of other professions. Four physicians, led by Benjamin Rush of Pennsylvania, signed the Declaration. Next, the signers included three farmers. The category can be misleading, as two of the men, William Floyd of New York and John Hart of New Jersey, owned large estates with enslaved workers. (In all, forty-one of the fifty-six signers were slave holders.) Only John Morton of Pennsylvania depended economically on a family farm without enslaved labor, although he also benefitted from being a public official in the years before independence. Similarly, it is impossible to limit Benjamin Franklin to a single profession. In this survey, he is counted as a printer since that was the primary source of his wealth, but, by the time of independence, Franklin’s professional life consisted more of politics and science. Finally, one full-time minister, John Witherspoon of New Jersey, signed the Declaration. Lyman Hall of Georgia was also a clergyman, but more actively practiced medicine by the time of independence.

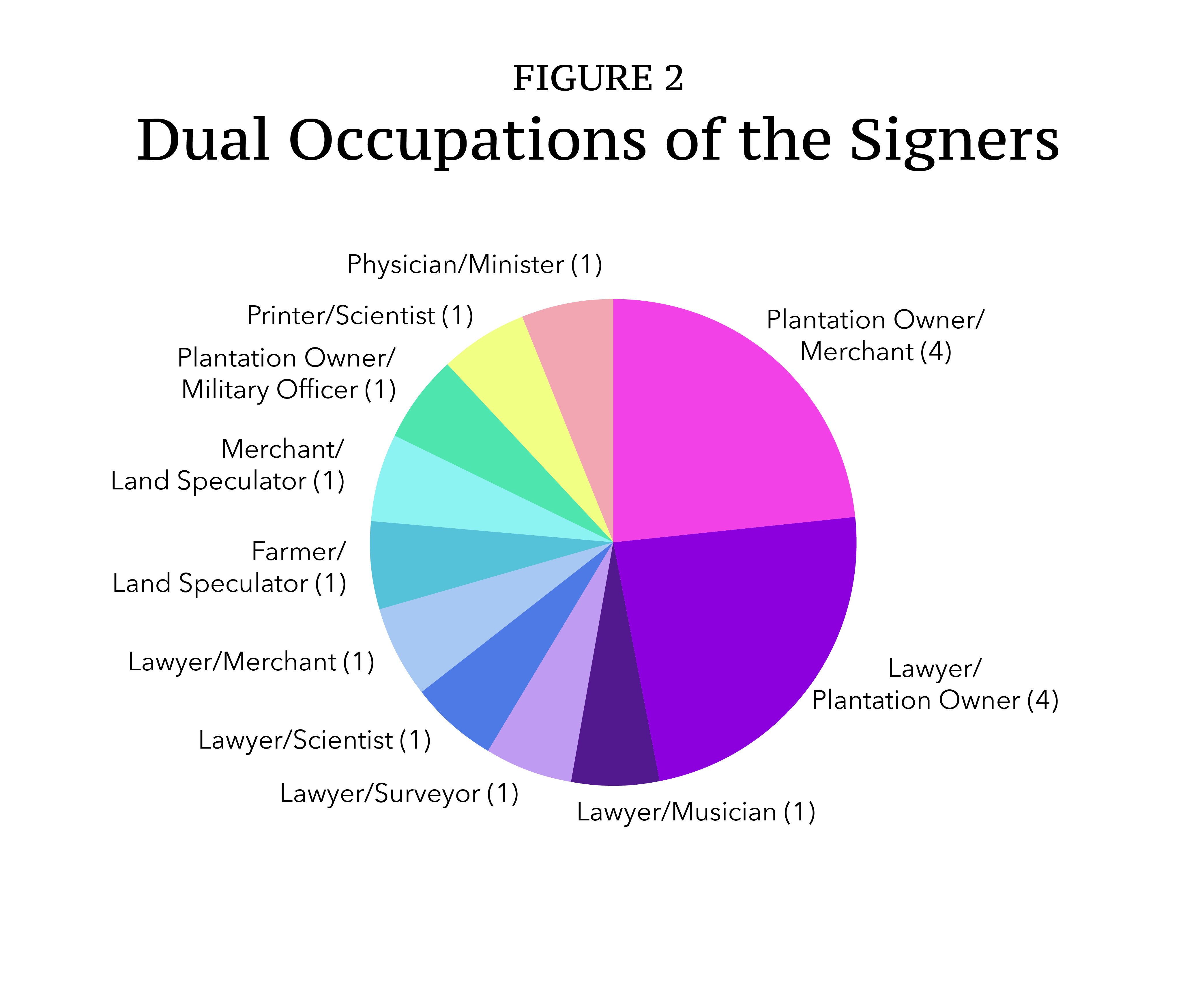

Limiting the signers to a primary profession helps to highlight their elite status, but it also conceals their economic diversity. At least one-third (seventeen) of the signers had more than one meaningful economic pursuit (Figure 2). This figure does not include several of the signers, including John Adams, who had a small farm that helped to provide for their family. At least some of this diverse economic enterprise can be attributed to the Enlightenment, what we might call the Benjamin Franklin effect. Francis Hopkinson of Pennsylvania was not only a lawyer but also an accomplished poet, satirist, harpsichordist, and composer.

The signers were also not always the richest men of their colonies. The famously spartan Samuel Adams relied on a new wardrobe gifted by Boston’s Sons of Liberty before he first traveled to Congress. Some delegates were not so lucky. In mid-September 1775, after returning from a brief recess, Richard Smith of New Jersey despaired that his “Homespun Suits of Cloaths” were “an Adornment few other Members can boast of.” Again, not every signer was Charles Carroll.[3]

The economic diversity of the signers had broad political implications. Most delegates to Congress might have been elites, but they still maintained close ties to the communities that sent them. In this sense, they were truly representative. Indeed, when at least ninety American localities and bodies composed their own declarations of independence between April and July 1776, many intended as instructions for their delegates to Congress, the representatives responded. The Declaration of Independence reflected the local declarations, particularly in its twenty-seven grievances against George III. Moreover, it mattered that the lead author of the Declaration, Jefferson, had two professions and multiple pursuits and that the Committee of Five included the polymath Franklin, lawyers John Adams and Roger Sherman, and merchant Robert Livingston.[4]

Even before declaring independence, the delegates in Philadelphia made significant financial sacrifices simply by serving in Congress. By 1776, Congress had taken on more of the character of a national government than merely a legislative body, and executing government functions required dozens of congressional committees that met in both the early morning and evening hours, between full sessions of Congress. Silas Deane of Connecticut served on so many committees that he turned the word into a verb, writing home that he was “in my old usual way Committeeing it away, and busy.”[5] The pace proved too much for Richard Smith. After recording his dizzying schedule for months in his diary, the delegate from New Jersey had more serious concerns than his homespun clothes. “I went Home,” Smith recorded on March 30, 1776, “having suffered in my Health by a close Attendance on Congress.” Although Smith continued his public career in New Jersey, he never returned to Congress.[6]

With such an exhausting schedule, few members of Congress could attend fully to their own financial affairs. That so many served long enough to even consider independence attests not only to their dedication but also to the labor of their families, particularly wives, and enslaved and hired workers who helped to maintain their farms and businesses. Consider the extraordinary example of Abigail Adams. As John “committeed” in Philadelphia, Abigail kept the farm at Braintree running all while confronting disease (dysentery followed by the threat of smallpox), British occupation, pregnancy, the death of her mother, and John’s obstinate reaction to her plea to “Remember the Ladies.”[7]

Of course, the delegates made their greatest financial risk by declaring American independence. It did not take long to see the potential consequences. In August 1776, just weeks after William Floyd signed the Declaration, the British army confiscated his estate on Long Island and used the property as a base of operations for the next seven years. In total, about one-third of the signers suffered damage to their homes during the Revolutionary War. Only America’s victory in the war ultimately limited the sacrifices by Floyd and other signers. The fate of the loyalists suggests how a different outcome in the war could have led to more permanent and extensive property losses for the signers and other leaders of the American cause.[8]

The professions and broader economic status of the signers contributed significantly to the Declaration of Independence. The elite station enjoyed by the members of Congress helped to legitimize the body and allowed its delegates to speak for the American people. In addition, the different and often multiple occupations held by the signers helped to ensure that the Declaration reflected the broad concerns of the communities they represented. Still, there is good reason we do not have an “Economic Interpretation of the Declaration of Independence.” Far from a motivation, economics acted as a deterrent-a reverse motivation-for signing the Declaration. In declaring independence, the signers created the United States of America and turned the Beard thesis on its head.

Denver Brunsman is associate professor of history at The George Washington University. He is the author of The Evil Necessity: British Naval Impressment in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World (University of Virginia Press, 2013), which received the Walker Cowen Memorial Prize for an outstanding work in eighteenth-century studies in the Americas and Atlantic world, and the co-editor, with David J. Silverman, of The American Revolution Reader (Routledge, 2013).

[1] Charles A. Beard, An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (New York: Macmillan, 1913). For the debate over Beard’s thesis, see Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: The “Objectivity Question” and the American Historical Profession (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 96–98, 240, 335–36.

[2] The following paragraphs and figures draw on the data in “Signers of the Declaration of Independence,” America’s Founding Documents, National Archives and Record Administration, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/signers-factsheet . For the importance of social and economic class to the political authority of the Continental Congress, see Benjamin H. Irvin, Clothed in Robes of Sovereignty: The Continental Congress and the People Out of Doors (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), esp. 19–51.

[3] Irvin, Clothed in Robes of Sovereignty, 25–26; Richard Smith, “Diary of Richard Smith in the Continental Congress, 1775–1776,” American Historical Review 1, no. 2 (1896): 290.

[4] Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), esp. 47–96, 105–23.

[5] Deane quoted in Jerrilyn Greene Marston, King and Congress: The Transfer of Political Legitimacy, 1774–1776 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 306.

[6] Richard Smith, “Diary of Richard Smith in the Continental Congress, 1775–1776. II,” American Historical Review 1, no. 3 (1896): 516.

[7] Woody Holton, Abigail Adams: A Life (New York: Free Press, 2009), 58–107.

[8] Fred W. Pyne, “William Floyd,” Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, https://www.dsdi1776.com/william-floyd/ ; “Biographical Sketches,” Signers of the Declaration, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/declaration/bio.htm.