The Education of the Men Who Signed the Declaration of Independence

by Caroline Winterer

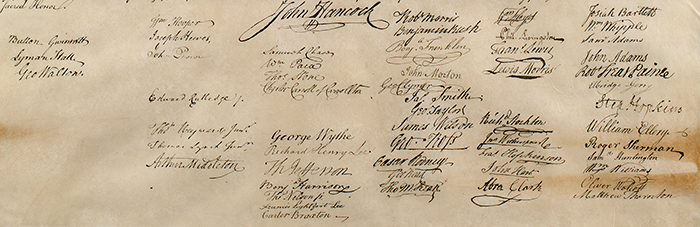

We call them “The Signers,” and that’s what they did. They signed the Declaration of Independence.

They were fifty-six men, signing in an age that prized beautiful penmanship as a mark of a fine education and the social rank that came with it. They dipped their feathered quills into an inkpot and tried . . . maybe a little too hard. There was a lot riding on those signatures.

You can’t miss the signature of Boston’s merchant prince John Hancock, which is two or three times as big as everybody else’s. At bottom right you’ll find Connecticut’s Oliver Wolcott, a lawyer and top graduate of Yale. A fluffy cumulus cloud of ink rises above his last name, as though lifted by the heat of his own importance. Near the middle is the signature of Philadelphia physician Benjamin Rush. With his Edinburgh medical education and the prefix Dr. usually announcing that fact to all and sundry, Rush could afford a plain vanilla signature. Just below Rush is another Benjamin: Benjamin Franklin, whose formal schooling ended when he was still a boy, perhaps overcompensating with a huge curlicue winding like a garden hose under his name.

They tried hard because they lived in an age when education marked you as a gentleman. A man of rank, wisdom, and influence. A man who wore a wig puffed into a meringue of decorum. The common school movement led by the Massachusetts farmer Horace Mann lay more than a half century in the future. Mann said each of us had an inner spark, and that all of us, no matter who we were or where we came from, deserved an education.

The Signers were not of that world. Their educations fit them to lead, and maybe even to rule. Behold the thick black loops and elegant curlicues of the sixteen merchants, twenty-five lawyers, and fourteen planters.[1] Their signatures are aspirational.

Consider Charles Carroll of Maryland, the only Catholic signer. He came from a family of so many Charles Carrolls that he wrote his address as part of his name on the Declaration of Independence: Charles Carroll of Carrollton. Carrollton was the vast Maryland plantation whose wealth helped to shield him from the omnipresent anti-Catholicism of his time and place. Shipped to France when he was eleven to be educated by the Jesuits, young Charles Carroll was drilled in their ratio studiorum, the rigid education in Latin, Greek, philosophy, and theology the Jesuit fathers taught to students around the world. That regularity shines through in the three identical letter C’s he affixed to the Declaration. The resulting signature was nearly as long as the John Hancock above it.

Other signatures project conspicuous modesty. John Witherspoon was the only cleric and the only college president to sign. He had sailed to America from Scotland, bristling with university degrees, to take the helm of Princeton (then called the College of New Jersey). His cramped signature seems to announce his Presbyterian faith’s view that we are all corrupted by original sin, awaiting an unmerited act of divine grace for salvation.

At the core of the Signers’ gentlemanly education was Greek and Latin. To be sure, there was a smattering of other subjects, such as geometry, logic, metaphysics, and moral philosophy.[2] But mostly it was wall-to-wall classicism.

Boys would start at the age of about five or six (in the appropriately named Latin schools) and continue all the way through college as part of the required curriculum. You couldn’t be a gentleman without at least some Latin and maybe even some Greek. Little boys would start by memorizing and reciting Latin passages, and turning Latin into English and English into Latin. Greek would begin with favorites like Homer and Thucydides teaching the deeds of great men. Or so it was hoped.

You can get a whiff of this in Thomas Jefferson’s August 1785 letter to his fifteen-year-old nephew, Peter Carr. Jefferson was among the most classically erudite of the founders. He could read both Greek and Latin. His plantation house, Monticello, is a temple to classicism. He quoted the Greeks and Romans right and left. He even quoted Homer in the original Greek on his wife’s tombstone. Jefferson wanted all this for his nephew.

So the helicopter uncle laid out a pretty standard course of classical reading. It looks alien to us, dull as dishwater, as though we’re digging up a forgotten civilization buried in the dust. But it’s what you’d have seen for any elite boy preparing for college at the time:

For the present, I advise you to begin a course of antient history, reading every thing in the original and not in translations. First read Goldsmith’s history of Greece. This will give you a digested view of that field. Then take up antient history in the detail, reading the following books, in the following order: Herodotus. Thucydides. Xenophontis Hellenica. Xenophontis Anabasis, Arrian, Quintus Curtius, Diodorus Siculus, Justin. This shall form the first stage of your historical reading, and is all I need mention to you now. The next, will be of Roman history. From that, we will come down to modern history. In Greek and Latin poetry, you have read or will read at school, Virgil, Terence, Horace, Anacreon, Theocritus, Homer, Euripides, Sophocles. Read also Milton’s Paradise Lost, Shakespeare, Ossian, Pope’s and Swift’s works, in order to form your style in your own language. In morality, read Epictetus, Xenophontis Memorabilia, Plato’s Socratic dialogues, Cicero’s philosophies, Antoninus, and Seneca.[3]

Jefferson signed the letter to his nephew exactly as he had signed the Declaration of Independence nine years earlier: “Th Jefferson.” The civic and the personal were totally intertwined. An education in Greek and Latin made you moral. It made you a gentleman. And it prepared you to lead. Or so it was hoped.

Look at the signature of Cæsar Rodney, a planter from Delaware. His first name was probably fun to have in an age that raised the ancient Greeks and Romans to the pinnacle of wisdom. Cæsar Rodney signed his first name with the “æ” ligature—the letters a and e smashed together. The æ ligature would have been in every Latin text he read. (Maybe Cæsar Rodney rode around in a phæton, a sporty carriage named for the Greek god Phæton.)

Fifty-six Signers is a lot of people. But they still left a lot of empty real estate at the bottom of the Declaration of Independence. It’s up to us to fill in those blanks with the people denied the education that catapulted the Signers to leadership.

In the big empty zone to the left of the elegant signature of South Carolina planter Arthur Middleton we can picture the hundreds of thousands of enslaved people forbidden to learn to read and write at all. Arthur Middleton was educated by private tutors in Charleston, and then at Cambridge University. But the classical education of so many of the Signers like Middleton is dimly reflected in the classical names they often gave their slaves. Names like Cæsar, this time given to demean rather than to exalt.[4]

Elite White women could get a smattering of Latin from older brothers or tutors at home. They were almost never taught Greek, forbidden because it was thought to turn girls into boys. Abigail Adams signed no public documents, let alone the Declaration of Independence. And she didn’t learn Greek. But she signed some letters to John Adams during the revolutionary war as “Portia,” the wife of Julius Cæsar’s assassin, Brutus.[5]

The Declaration of Independence is so familiar to us that it’s easy to forget how different the Signers’ world was from our own. But just a few minutes with their signatures opens up their lost era, way beyond the famous John Hancock that still dominates the document.

Caroline Winterer is the William Robertson Coe Professor of History and American Studies and the chair of the Department of History at Stanford University. Her most recent book is Time in Maps: From the Age of Discovery to Our Digital Era (University of Chicago Press, 2020), edited with her Stanford colleague Karen Wigen. She is also the author of four other books, including American Enlightenments: Pursuing Happiness in the Age of Reason (Yale University Press, 2016).

[1] National Archives chart: https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/signers-factsheet .

[2] A Harvard student notebook from the early eighteenth century is here: https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:46422049$24i .

[3] Thomas Jefferson, letter to Peter Carr, Paris, August 19, 1785: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/let31.asp .

[4] Margaret Williamson, “‘Nero, the mustard!’: The Ironies of Classical Slave Names in the British Caribbean,” in Classicisms in the Black Atlantic, ed. Ian Moyer, Adam Lecznar, and Heidi Morse (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), 57–78.

[5] Available by searching for “Portia” here: https://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/archive/letter/ . On American women and classicism, see The Mirror of Antiquity: American Women and the Classical Tradition, 1750–1900 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007).