Jewish Athletes and the Challenges of American Sports

by Jeffrey S. Gurock

The world of American sports has long offered the athletically inclined Jew with grand opportunities for achievement, acceptance, and even glory within this country’s society. But the road to success on the track, in stadiums, or in arenas generally has come at the price of the abandonment of ties to ancestral faith or, at least, undermined commitment to the demands of their religion. Breaks with the past in the quest to make it in this realm have been, moreover, a source of intergenerational tensions within families and have challenged religious leaders to find ways to reconcile the secular lure of the gym with the calls of Jewish practice. At the same time, ironically, when properly expressed, the fame that has accrued to outstanding Jewish athletes, who have stood up for their faith and people, has been a source of pride and even sustained identification for American Jews. The iconic stories of baseball stars Hank Greenberg in the 1930s, Sandy Koufax in the 1960s, and, more recently, Olympic champion gymnast Aly Raisman all underscore the complexity of the relationship between Judaism and sport. The durée of this challenge dates to the life stories of thousands of less renowned Jewish immigrants and their children who were caught up in the excitement of sports in downtown newcomer quarters, most notably New York’s Lower East Side.

The world of American sports has long offered the athletically inclined Jew with grand opportunities for achievement, acceptance, and even glory within this country’s society. But the road to success on the track, in stadiums, or in arenas generally has come at the price of the abandonment of ties to ancestral faith or, at least, undermined commitment to the demands of their religion. Breaks with the past in the quest to make it in this realm have been, moreover, a source of intergenerational tensions within families and have challenged religious leaders to find ways to reconcile the secular lure of the gym with the calls of Jewish practice. At the same time, ironically, when properly expressed, the fame that has accrued to outstanding Jewish athletes, who have stood up for their faith and people, has been a source of pride and even sustained identification for American Jews. The iconic stories of baseball stars Hank Greenberg in the 1930s, Sandy Koufax in the 1960s, and, more recently, Olympic champion gymnast Aly Raisman all underscore the complexity of the relationship between Judaism and sport. The durée of this challenge dates to the life stories of thousands of less renowned Jewish immigrants and their children who were caught up in the excitement of sports in downtown newcomer quarters, most notably New York’s Lower East Side.

Of all the attitude adjustments immigrant Jews had to make with American culture, coming to grips with this country’s embrace of physicality proved to be among the most difficult. Where they came from in Eastern Europe, athleticism was not valued. Reverence for the head, for the intellect, much more than the cultivation of the body was where the emphasis lay. While Jews, when under attack during pogroms, were thankful for strong men who fought back for them, few families really wanted their sons to be tough guys—muscle men—even if working-class Jews had calluses on their hands. When they came to an early twentieth-century America that idealized, for example, a rough-riding chief executive, who enjoyed striking pugilistic poses while stripped to the waist to display his fighting pose, they required a fundamental change in their approach to life. Few families easily made that transition.

The immigrants’ children, on the other hand, clearly understood that being physical was a fundamental American trait as they were bombarded from all sides with the promises, possibilities, and necessity of sports. In the public schools, to begin with, participation in physical training was emphasized to inculcate in young people the virtues of self-reliance and unselfish cooperation, two fine Rooseveltian qualities. Similarly, downtown settlement houses pushed comparable transformative messages. In both cases, coaches presented themselves as new role models and told—or at least implied to—their youthful charges that their parents were out of step with America. These perceptions fostered disrespect toward mothers and fathers among Jewish boys and girls who had become enamored by the culture of the gym. The tension within immigrant households cut both ways as parents often looked upon their athletic sons and daughters as loafers who were spending their spare time at play rather than at work helping the family rise out of poverty.

For the minority of parents who harbored strong religious values—and the many others who at least possessed traditional Orthodox sensibilities—their straying sons and daughters were “bums,” to use the vernacular of the time, who were breaking with their faith’s demands. The fact was that Judaism’s clock and calendar differed fundamentally from America’s. To be great in sports required nothing less than a seven-day-a-week commitment to training and competition, which meant that the Sabbath, the Jewish day of rest, could not be observed. The training table presented protein dishes that strengthened bones, but the foods were not kosher. Even the High Holidays would be a problem for the aspiring athlete if games or practice took place on those holiest of days. Some players did not care at all about their ancestral traditions. Others, however, assuaged whatever guilt they felt by seeing themselves as champions of Jewish ethnic pride by showing how American their people could be through victories on the playing field. Still others created in their minds and behaviors a hierarchy of Jewish holidays that they would be attuned to, with Yom Kippur being the most important.

Religious leaders made yeoman efforts to create modern synagogues—with all due allegiance to Jewish teachings—that would create athletic environments with the hope that those who came initially just to pray might stay to play. But only a minority of youngsters opted for that answer to the dilemmas of religion and sports.

In the 1930s, Detroit Tigers first baseman Hank Greenberg was the most famous Jewish athlete of the era. He had achieved glory on the basepaths and in his quest for stardom he had moved away from traditional patterns of religious observance. But on Yom Kippur, 1934, when he faced a moment of truth, Greenberg stood up tall for his faith and people. On that day in the Jewish calendar, his ball club was in a close pennant race for the American League crown and Greenberg was pressured to play. His manager and club owners made it clear that he had an obligation to his community—not the Jewish community, but the Detroit community—to perform. Greenberg refused, and in so doing gave Jews in Detroit a strong sense of ethnic pride at a time when in that city, and generally in America, Jews were disrespected and where various forms of antisemitism troubled them.

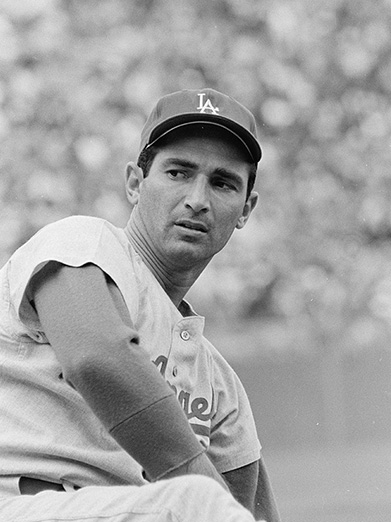

In 1965, a far more understanding American society did not question the great Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Sandy Koufax’s decision to stay away from the ballpark on Yom Kippur. In so doing, this most popular Jewish sportsperson of his era made a statement to the Jewish community—especially to youngsters—about how important Jewish identity should be to them. In more recent years, with the number of Jewish ball players increasing in the Major Leagues, and with the decision to play or not to participate also left totally up to them, Yom Kippur has become a good way of calibrating athletes’ levels of interest or disinterest in Judaism.

Finally, in another crucial arena, at the London Olympics of 2012, female gymnast Aly Raisman made an important statement about her Jewish identity and connection to her people. These international gatherings have historically not been favorably disposed towards Jews and, in some instances, they have been downright antagonistic. One egregious occurrence took place at the Berlin games of 1936 when the Jewish trackmen Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller were denied the chance to compete in a signature Olympic event because the heads of the American Olympic Committee did not want to embarrass their friend Adolf Hitler with the sight of two Jews on a victory stand in front of 80,000 fans. Even worse, in 1972 during the Munich Olympiad when Palestinian terrorists murdered eleven Israeli athletes, the International Olympic Committee determined that the sports carnival would go on after one flaccid day of mourning. Forty years later, at the London games, that same international sports body turned down the request of the Israeli athletic contingent to memorialize that tragedy at the opening ceremonies. Several days later, during the outstanding floor exercise that helped garner one of her two gold medals, Raisman made her own positive statement as a proud Jew by using “Hava Nagila,” one of the best known Jewish tunes, as her musical accompaniment. She let the world know where she stood on the victory stand.

Finally, in another crucial arena, at the London Olympics of 2012, female gymnast Aly Raisman made an important statement about her Jewish identity and connection to her people. These international gatherings have historically not been favorably disposed towards Jews and, in some instances, they have been downright antagonistic. One egregious occurrence took place at the Berlin games of 1936 when the Jewish trackmen Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller were denied the chance to compete in a signature Olympic event because the heads of the American Olympic Committee did not want to embarrass their friend Adolf Hitler with the sight of two Jews on a victory stand in front of 80,000 fans. Even worse, in 1972 during the Munich Olympiad when Palestinian terrorists murdered eleven Israeli athletes, the International Olympic Committee determined that the sports carnival would go on after one flaccid day of mourning. Forty years later, at the London games, that same international sports body turned down the request of the Israeli athletic contingent to memorialize that tragedy at the opening ceremonies. Several days later, during the outstanding floor exercise that helped garner one of her two gold medals, Raisman made her own positive statement as a proud Jew by using “Hava Nagila,” one of the best known Jewish tunes, as her musical accompaniment. She let the world know where she stood on the victory stand.

Jeffrey S. Gurock is the Libby M. Klaperman Professor of Jewish History at Yeshiva University. He is the author of twenty-five books, including Marty Glickman: The Life of an American Jewish Sports Legend (New York University Press, 2023), Parkchester: A Bronx Tale of Race and Ethnicity (New York University Press, 2019), Jews in Gotham: New York Jews in a Changing City (New York University Press, 2012; repr. 2015), and Judaism’s Encounter with American Sports (Indiana University Press, 2005).