The Role of Jewish Americans in the Civil Rights Movement

by Cheryl Greenberg

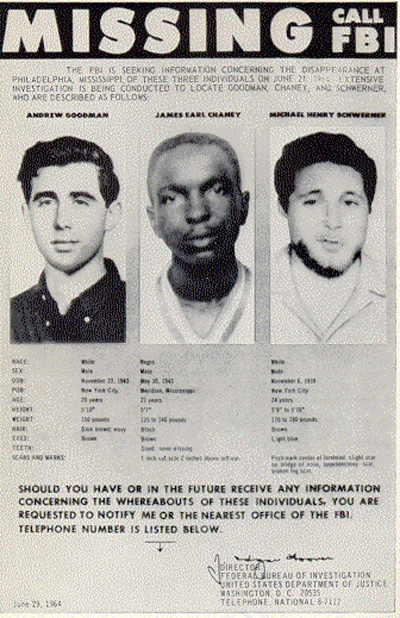

American Jews played an outsized role in the Civil Rights Movement, both in number and prominence. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel marched with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Rabbi Joachim Prinz spoke at the 1963 March on Washington. Of the three civil rights workers killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi, in 1964 at the start of Freedom Summer, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman were Jewish, and James Chaney African American. Jack Greenberg along with Thurgood Marshall and others convinced the Supreme Court to desegregate public schools in Brown v. Board of Education. Chuck McDew, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee from 1960 to 1963, was an African American Jew.

American Jews played an outsized role in the Civil Rights Movement, both in number and prominence. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel marched with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Rabbi Joachim Prinz spoke at the 1963 March on Washington. Of the three civil rights workers killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi, in 1964 at the start of Freedom Summer, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman were Jewish, and James Chaney African American. Jack Greenberg along with Thurgood Marshall and others convinced the Supreme Court to desegregate public schools in Brown v. Board of Education. Chuck McDew, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee from 1960 to 1963, was an African American Jew.

Many more Jewish Americans, White and Black, worked in less public roles as advocates, lawyers, organizers, marchers, lobbyists, and fundraisers, in far greater numbers than one might expect, given they are approximately three percent of the White population.

This Jewish commitment to civil rights was not a foregone conclusion, however. Collaboration between Black and (White) Jewish activists had begun only at the turn of the twentieth century and grew slowly from there. Few Jews (at this time primarily hailing from Spain, Portugal, Germany, or elsewhere in Western Europe) joined the abolitionist movement, for example, and many southern Jews held enslaved people or otherwise collaborated with the slave system.

At the end of the nineteenth century, two migrations coincided: African Americans began moving into cities and into the North to escape crop failures and crippling Jim Crow strictures in such numbers that we call it the Great Migration. At the same time migrants from Eastern and Southern Europe, including approximately two million Jews, moved into many of those same cities. Both communities faced discrimination from local White people and sometimes by better-educated Jews or African Americans already there.

To “civilize” their compatriots and to challenge the bigotry and discrimination they faced, both the African American and Jewish American communities organized self-help and political organizations such as the National Association of Colored Women (1896), the NAACP (1909), and the National Urban League (1911) in the Black community, and the National Council of Jewish Women (1893), the American Jewish Committee (1906), the Anti-Defamation League (1913), and the American Jewish Congress (1917) in the Jewish community.

A large number of Eastern European Jews, already radicalized by European unionizing and leftist ideologies, brought that perspective and energy to the United States with them, and swelled the ranks of the socialist, communist, and union efforts getting started across the country. Joined by many African Americans radicalized by their oppressive working conditions, these activists organized among the working class, establishing, for example, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (1900) and the (African American) Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (1925), both of which, unusually, accepted men and women, as well as both races, on equal footing. Leftist and union organizing also led, later, to the Jewish Labor Committee (1934) and the Negro Labor Committee (1935). All these organizations worked in their own ways to challenge bigotry against their own group, although only those on the left worked across racial lines. In other words, although the NAACP and the Anti-Defamation League used both legal and political means to fight discrimination against Black or Jewish people respectively, neither fought explicitly for the rights of the other.

Outside the left, individuals from both groups did work together. Among the White founders and early leaders of the NAACP, for example, a disproportionate number were Jews, including Lillian Wald, Emil Hirsch, Julius Rosenwald (who also built schools for southern Black children and supported Black artists), Stephen Wise, Joel and Arthur Spingarn, and Henry Moskowitz. Black scholar Alain Locke and White Jewish scholars Franz Boas and Horace Kallen posited the equal status of all racial and ethnic groups. African American journalists followed the violence against Jews in Eastern Europe and the rise of Nazism, while a number of Yiddish newspapers covered southern lynchings, calling them “pogroms.” Both communities recognized the plight of the other, although there was little collaborative work done outside the Socialist and Communist parties and left-leaning unions.

What brought liberal Black and Jewish activists together was primarily the rise of Nazism and Fascism both in Europe and the US. For American Jews, a broad-based attack on bigotry offered important advantages. First, given the immense threat, this universal appeal brought desperately needed allies to help fight antisemitism. Second, many Jews feared calling attention to antisemitism specifically for fear of providing it a wider public platform. Meanwhile, African American political organizations seized the opportunity to highlight the same racist practices at home that the Nazis were using in Germany, in efforts like the Double V Campaign. (In fact, the Nazis modeled many of their racial laws on American Jim Crow laws.) By linking antisemitism and racism, African American groups could expand their reach.

Black and Jewish collaboration on civil rights in this early period, then, was based on a decision among leaders in both communities to work together to further mutual goals. To strengthen this mutual commitment, Black and Jewish leaders and the leftist press emphasized the common plight of the two groups, and their parallel histories of oppression. “The Case for Negro and Jewish Unity: This Is Our Common Destiny!” pronounced the Black New York magazine People’s Voice in 1943. “The Klan is a threat [to Jews] today!” a 1941 ADL leaflet insisted. They were aided in universalizing their message by shifting political imperatives in the US, first to encourage unity for the war effort, and later to call for racial and religious tolerance given the horrors of the genocidal Holocaust in Europe.

Ironically, the Cold War also played a role in strengthening a broad understanding of civil rights. Because the goal was to win over non-aligned nations, virtually all of which were populated by people of color, the US had to embrace equality, at least rhetorically. As it was, segregation was the best argument the Soviet Union had to win these nations to their side. The Cold War also provoked an anti-communist hysteria that, while discrediting more dramatic proposals for equality as “communist,” nevertheless strengthened other civil rights efforts as progressives fleeing McCarthyist labels brought their egalitarian goals to liberal organizations.

This newly energized post–World War II movement for civil rights challenged segregation and discrimination on many fronts. The call was equality for all, regardless of “race, creed or color,” linking the interests of all marginalized people regardless of which group any particular law targeted. While many ethnic and religious groups engaged with this work, Jews were greatly overrepresented in terms of both activists and organizations. Both Black and Jewish legal groups, often working together, challenged segregation in colleges, professional organizations, housing, stores, and beaches, and lobbied for a federal anti-lynching law and the end of poll taxes and literacy tests that prevented so many Black southerners from voting. The NAACP lobbied in the UN to support the Partition of Palestine and the creation of Israel. The Rosenwald Fund supported Kenneth and Mamie Clark’s research on Black children’s racial attitudes (the “doll study”) that helped determine several desegregation decisions including Brown. Both the NAACP and the ADL were skeptical of the interracial group the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) sent to ride trains through the South in 1947 to test the Supreme Court decision banning segregation on interstate transport (the “Journey of Reconciliation”), but praised the effort after the fact and helped cover legal costs.

![Civil rights leaders meet with President John F. Kennedy in the oval office of the White House after the March on Washington, August 28, 1963 [Photograph shows (left to right): Mathew Ahmann (National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice); Whitney Young (National Urban League); Martin Luther King Jr. (SCLC); John Lewis (SNCC); Rabbi Joachim Prinz (American Jewish Congress); Reverend Eugene Carson Blake (United Presbyterian Church); A. Philip Randolph; President John F. Kennedy; Walter Reuther (labor leader), with Vice President Lyndon Johnson partially visible behind him; and Roy Wilkins (NAACP).] (Library of Congress)](/sites/default/files/2024-06/MarchWashington1963_Library%20of%20Congress.jpg) New civil rights groups like Dr. Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the American Jewish Congress’s Commission on Law and Social Action, and the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (led by an African American and a Jew), all of whom included both Black and Jewish people in leadership positions, joined existing groups like CORE and local civil rights projects. Close to half of the White lawyers working in the movement in the South were Jewish. Jews figured prominently among the Freedom Riders (the 1961 version of the Journey of Reconciliation) and the activists in Mississippi’s 1964 Freedom Summer.

New civil rights groups like Dr. Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the American Jewish Congress’s Commission on Law and Social Action, and the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (led by an African American and a Jew), all of whom included both Black and Jewish people in leadership positions, joined existing groups like CORE and local civil rights projects. Close to half of the White lawyers working in the movement in the South were Jewish. Jews figured prominently among the Freedom Riders (the 1961 version of the Journey of Reconciliation) and the activists in Mississippi’s 1964 Freedom Summer.

Hundreds of (mostly northern) Jewish rabbis participated in southern demonstrations and marches. By and large, however, the Jews most likely to get involved in civil rights activities, especially in the difficult and dangerous work of community organizing, were those least likely to be religious. The devout Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel was more of a rarity than the children of communists and other progressives. And Reform Jews, the least observant of the Jewish denominations, were far more commonly in the activist ranks than the Orthodox. In short, while many Jews explained Jewish engagement with civil rights as springing from their religious ethics, the situation was more nuanced. For a variety of reasons, after World War II, Reform (and some Conservative) Jews increasingly emphasized the ethical aspects of Judaism over ritual. In some ways, civil rights became a way to define one’s Jewishness. This is not at all to diminish the very real risks these Jews took, or to question their deep commitment to the cause of equality. Rather, it is to see the ways Jewish identity was increasingly defined by ethics, as more and more Jews moved toward lesser ritual observance.

There are, of course, multiple Jewish communities. Jews of color naturally embraced civil rights. Northern White Jews coming from progressive political roots did so as well. For them, the system of oppression was ubiquitous and only a unified attack on all forms of bigotry and hatred could produce real change. Jewish liberals, who believed in race blindness and found Black radicalism problematic, nevertheless continued to support more “mainstream” civil rights efforts, seeing them as a requirement for a society that protected Jews as well as Black and other marginalized populations. (This is why so many Jews and political Jewish organizations are also on the front lines of feminist and LGBTQ struggles.)

Most southern Jews, on the other hand, and some Jewish small business owners, especially outside the larger cities, tended to feel more hostile toward, or threatened by, civil rights advances. They believed their self-interest lay not in embracing difference but defending their White or middle-class status. This is why despite robust collaborative relationships between African American and Jewish American political activists, tensions continued to roil the two communities. White Jews, who had succeeded economically beyond their Black counterparts, thanks to their lighter skin and access to opportunities and programs most Black people could not utilize, often found themselves in hierarchical relationships with Black clients, students, employees, or renters. Such economic and sometimes status divides were in many cases interpreted as Black-Jewish tensions.

Both the solid Jewish support for civil rights, well beyond that of other White Americans, and the economic tensions between many African Americans and Jewish Americans, reveal how deeply enmeshed the two communities understand themselves to be. Even today, Congress has a “Black-Jewish Caucus” whose members work together to advance civil rights and human rights issues that both communities believe are central to their own security and ability to flourish.

Cheryl Greenberg is the Paul E. Raether Distinguished Professor of History, Emerita, at Trinity College. She is the co-author, with Joe Bateman, of A Day I Ain’t Never Seen Before: Remembering the Civil Rights Movement in Marks, Mississippi (University of Georgia Press, 2023); author of Troubling the Waters: Black-Jewish Relations in the American Century (Princeton University Press, 2006); and editor of A Circle of Trust: Remembering SNCC (Rutgers University Press, 1998).