The Jewish Imprint on American Musical Theater

by Elizabeth L. Wollman

Long celebrated as one of the most quintessentially American of entertainment genres, Broadway musicals delight audiences with glitz, glitter, and polish; send them home with at least a glimmer of hope; and celebrate America’s promise as a melting pot. Pastiches almost by definition, musicals borrow from and recycle countless other arts genres, aesthetics, and styles. Broadway musicals serve up thick slices of cultural idealism at its American dreamiest.

Long celebrated as one of the most quintessentially American of entertainment genres, Broadway musicals delight audiences with glitz, glitter, and polish; send them home with at least a glimmer of hope; and celebrate America’s promise as a melting pot. Pastiches almost by definition, musicals borrow from and recycle countless other arts genres, aesthetics, and styles. Broadway musicals serve up thick slices of cultural idealism at its American dreamiest.

Musicals are such a hodgepodge of influences that they are somewhat like archeological digs, given the layers of cultural, political, regional, stylistic, and artistic influences they draw from. Scratch below the surface of any Rodgers and Hammerstein classic and you’ll encounter doses of operetta here, smatterings of vaudeville-inspired buffoonery there, hints of burlesque when the lights go low. Enjoy a show by mid-century composers and lyricists like Harold Rome, Irving Berlin, Kander and Ebb, Comden and Green, or Stephen Sondheim—or, for that matter, one by contemporaries like Jeanne Tesori, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Jason Robert Brown, or Robert Lopez—and you may detect jazz, opera, classical music, gospel, blues, folk, or any style of popular song. One reason for this crush of influences is to ensure that Broadway musicals appeal to and include of all kinds of audiences. Musicals don’t belong to some people more than others. They are democratic in their attempts to spread pleasure as widely as possible.

Musicals’ broad appeal might seem to contradict the fact that they—along with the commercial theater industry that develops, packages, and sells them—were created by a disproportionate number of Jewish immigrants, or children of immigrants, all relative newcomers to America. But then, assimilation is hardly unique to Jewish immigrants: new Americans from all backgrounds assimilate in broadly similar ways. Newcomers, especially those driven in large numbers from their homelands, arrive in the US with little cultural access, status, or means. They find shelter and employment in neighborhoods and workplaces that are at least begrudgingly tolerant of them, work hard to acculturate, and hope that, as the American Dream promises, their lives and those of their offspring will gradually get easier and more prosperous.

The fact that the modern theater industry and its musicals were largely honed by Jews is a result of numerous interrelated factors, including immigration and urbanization patterns, significant industrial advances, tolerance, and timing. Theories about why so many Jewish immigrants ended up working in early twentieth-century American entertainment relate to Diaspora Jews’ generations of experience creating secular music and theater for wider audiences; their relegation to careers in finance, sales, and textile-making; and, like other disenfranchised or minority groups, a split consciousness that allows them to willingly subsume or repudiate aspects of their ethno-religious identity in exchange for acculturation and acceptance by a dominant majority.

The fact that the modern theater industry and its musicals were largely honed by Jews is a result of numerous interrelated factors, including immigration and urbanization patterns, significant industrial advances, tolerance, and timing. Theories about why so many Jewish immigrants ended up working in early twentieth-century American entertainment relate to Diaspora Jews’ generations of experience creating secular music and theater for wider audiences; their relegation to careers in finance, sales, and textile-making; and, like other disenfranchised or minority groups, a split consciousness that allows them to willingly subsume or repudiate aspects of their ethno-religious identity in exchange for acculturation and acceptance by a dominant majority.

Jews have lived in the US since the colonial era, but the largest numbers arrived from central and eastern Europe between the mid-nineteenth and early twentieth century. Between the 1880s and the 1920s alone, 2.8 million Jews fled virulent antisemitism and violent pogroms in regions they’d inhabited for generations. Their arrival in America coincided with the Gilded Age, a period of significant urbanization and industrialization. By 1910, the Jewish population of New York City surpassed one million; the city remains home to the largest urban concentration of Jews worldwide.

American entertainment grew and diversified as America urbanized. In the 1890s, when New York’s entertainment center was still concentrated in Manhattan’s Union Square and an underground transit system terminating in Longacre (now Times) Square was being dug, theater owners and producers began to relocate north to that comparatively cheap, underdeveloped neighborhood. Six theater managers and booking agents who individually owned or operated most of the venues in New York and around the country capitalized on the momentum by consolidating. The Theatrical Syndicate, as they called themselves, effectively monopolized the growing theater industry, thereby mirroring empire-building tactics of other industries in the Gilded Age.

The Syndicate made enemies: some competing theater owners, managers, and performers boycotted them at their own risk. Some opposition to them was clearly antisemitic: because five of the six members were Jewish, one theater critic labeled them “the Sheeniedicate” and warned readers that their poor taste, coarseness, and obsession with money would destroy the artistry of American theater. Even so, the Syndicate’s powerful monopoly was only broken by younger, hungrier Jewish immigrants in the nineteen-teens: the Shubert brothers, who built a powerful theater empire that continues to operate on Broadway and beyond.

As such battles for control of American theater occurred behind the scenes, the contemporary musical—in which songs, characters, and movement tell a cohesive story—emerged from a mix of genres including blackface minstrelsy, extravaganza, burlesque, vaudeville, operetta, melodrama, pantomime, and various dance styles. Landmark productions that paved the way for modern musicals include Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle’s all-Black, character-driven Shuffle Along (1921), Jerome Kern’s plot-based musicals for the tiny Princess Theatre, and Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II’s multigenerational saga, Show Boat (1927).

As such battles for control of American theater occurred behind the scenes, the contemporary musical—in which songs, characters, and movement tell a cohesive story—emerged from a mix of genres including blackface minstrelsy, extravaganza, burlesque, vaudeville, operetta, melodrama, pantomime, and various dance styles. Landmark productions that paved the way for modern musicals include Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle’s all-Black, character-driven Shuffle Along (1921), Jerome Kern’s plot-based musicals for the tiny Princess Theatre, and Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II’s multigenerational saga, Show Boat (1927).

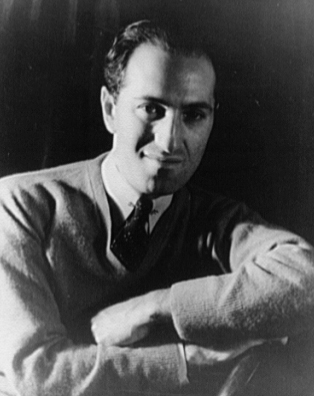

Jews were hardly the only minority group involved in theater making, but their prominence was hard to deny. Kern, a middle-class Jew born in Manhattan to immigrant parents, was a contemporary of the Lithuanian immigrant Irving Berlin, whose family was so devastatingly poor that he quit school at age eight to help support them as a peddler, singing waiter, and eventually, prolific Tin Pan Alley composer. George and Ira Gershwin, Richard Rodgers, and Lorenz Hart were all children of Jewish immigrants. Oscar Hammerstein II, whose paternal grandfather was a German Jewish theater impresario, was raised as a Universalist but identified culturally as Jewish. The wealthy, midwestern Cole Porter was decidedly not Jewish, but once confessed to Rodgers that his secret to success was to try to compose “Jewish tunes.”

Of course, a true Jewish imprint on musicals could only go so far: general audiences would not have tolerated musicals if they were not broadly appealing. This helps explain why there are so few canonized musicals specifically about Jews: Fiddler on the Roof (1964) is an exception, as its success is linked to its universal themes: familial love, the generation gap, the underdog, the American dream. Cabaret (1966), Falsettos (1992), and Caroline, or Change (2004) all feature Jewish characters, even as they also focus on broader themes: sociopolitical disorder, illness, gender identity, family dynamics, coming-of-age, and class and race differences. Most musicals that explore Jewish life—like Milk and Honey (1961), I Can Get It for You Wholesale (1962), Rags (1986), and The People in the Picture (2011)—have fared less well in cultural memory.

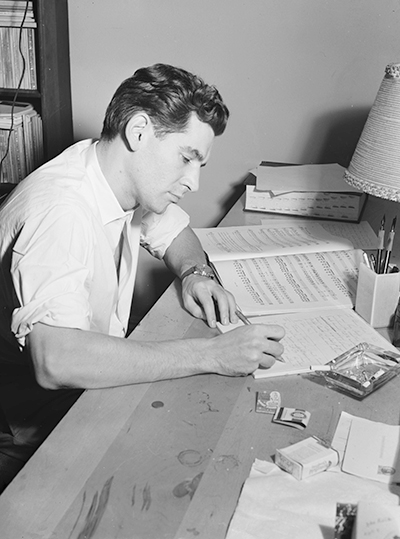

Which brings us back to the idea of musicals as archaeological digs. While overt Jewishness is comparatively rare, subtle references to Jewish life and culture abound in musicals. Take the opening bars of Leonard Bernstein’s score for West Side Story (1959). The creative team intended the musical, initially titled East Side Story, to depict Jews and Christians clashing during Easter and Passover. That idea was scrapped, but the first notes of the musical still quote the Rosh Hashanah “Tekiah g’dolah” shofar blast. In Bernstein’s adaptation of Voltaire’s Candide (1956), his Old Lady, forever hopeful despite a life of violence and displacement, sings a number he originally titled “Old Lady’s Jewish Tango,” which he jokingly wrote on his score should be played “moderato Hassidicamente.” The song, reworked as “I Am Easily Assimilated,” was scrubbed of obvious indicators that the character had been reimagined as a Jew bouncing endlessly and often unpleasantly across the Diaspora.

Which brings us back to the idea of musicals as archaeological digs. While overt Jewishness is comparatively rare, subtle references to Jewish life and culture abound in musicals. Take the opening bars of Leonard Bernstein’s score for West Side Story (1959). The creative team intended the musical, initially titled East Side Story, to depict Jews and Christians clashing during Easter and Passover. That idea was scrapped, but the first notes of the musical still quote the Rosh Hashanah “Tekiah g’dolah” shofar blast. In Bernstein’s adaptation of Voltaire’s Candide (1956), his Old Lady, forever hopeful despite a life of violence and displacement, sings a number he originally titled “Old Lady’s Jewish Tango,” which he jokingly wrote on his score should be played “moderato Hassidicamente.” The song, reworked as “I Am Easily Assimilated,” was scrubbed of obvious indicators that the character had been reimagined as a Jew bouncing endlessly and often unpleasantly across the Diaspora.

Plenty of characters in musicals, while not labeled as Jewish, can easily be interpreted as such. The flirtatious Persian peddler Ali Hakim and the brooding outsider Jud Fry from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! (1943), and Luther Billis and Emile de Becque from their South Pacific (1949), have been read as Jewish. So have characters from Jerry Herman’s Hello, Dolly! (1964) and Irving Berlin’s Annie Get Your Gun (1946). Stephen Sondheim’s works feature countless angsty, lost, anxious characters who could easily be Jewish; his opus, too, has been likened to the Talmud in its depth, breadth, and contradictoriness. Yet Sondheim specified only a single character in his corpus as explicitly Jewish: Paul, one of the many married friends of “Bobby-bubbe” in Company (1970). Sondheim’s artistry is cherished not because of his real or interpreted references to Judaism, but because his musicals are so nuanced, complex, and profound.

The need to subsume one’s differences to appeal to a majority might seem lamentable, but it can as easily be interpreted as celebratory: musicals are not supposed to be exclusive or overly concerned with one kind of American at the expense of others. At their best, they send all audiences away feeling warm, happy, moved—and included. I can’t imagine a more Jewish value.

Elizabeth L. Wollman is a professor of music at Baruch College and a member of the doctoral faculty in theatre at the CUNY Graduate Center. She is a specialist in the contemporary musical, about which she has written many books, chapters, and articles, including The Theater Will Rock: A History of the Rock Musical, from Hair to Hedwig (University of Michigan Press, 2006), Hard Times: The Adult Musical in 1970s New York City (Oxford University Press, 2013), and A Critical Companion to the American Stage Musical (Methuen Drama, 2017). With Jessica Sternfeld, she was co-editor of The Routledge Companion to the Contemporary Musical (2020), and she currently co-edits the journal Studies in Musical Theatre.