The Declaration of Independence: America’s Call to Arms to Spain and France

by Larrie D. Ferreiro

Early in the throes of the American Revolution in the summer of 1776, Thomas Jefferson was wrestling with a document to King Carlos III of Spain and King Louis XVI of France that would bring much-needed help to the embattled American colonies. The colonies had been at war with Britain for more than a year now, and the military situation was dire. Without the direct intervention of Britain’s adversaries, Spain and France, on America’s side, the colonies could not hope to prevail against the superior British army and navy.

Early in the throes of the American Revolution in the summer of 1776, Thomas Jefferson was wrestling with a document to King Carlos III of Spain and King Louis XVI of France that would bring much-needed help to the embattled American colonies. The colonies had been at war with Britain for more than a year now, and the military situation was dire. Without the direct intervention of Britain’s adversaries, Spain and France, on America’s side, the colonies could not hope to prevail against the superior British army and navy.

The colonists already had decided to break free from British rule. Bolstered by the battles at Lexington and Concord, and certain that the ongoing war had irrevocably separated America from Britain, the colonial governments sent their delegates to the Continental Congress with instructions “immediately to cast off the British yoke” and “to concur with the delegates of the other Colonies in declaring Independence.”[1] However, the American nation had begun its armed struggle against British rule almost completely incapable of fending for itself, like a rebellious child who takes leave of his family without a penny to his name. It had no navy, little in the way of artillery, and a ragtag army and militia that were bereft of even the most basic ingredient of modern warfare: gunpowder. Soon after the Battle of Bunker Hill, Benjamin Franklin noted that “the Army had not 5 Rounds of Powder a Man. . . . The World wonder’d that we so seldom fir’d a Cannon. We could not afford it.”[2] America, in short, desperately needed to bring Spain and France into the conflict.

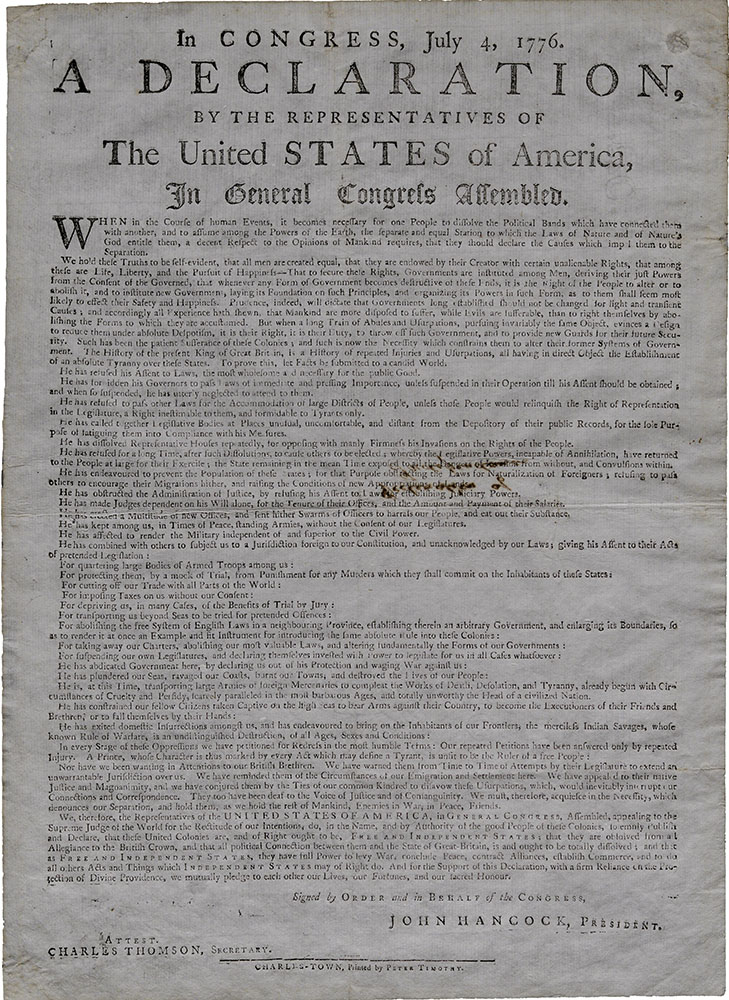

Neither Carlos III nor Louis XVI would take sides in a British civil war; America had to demonstrate that it was an independent nation fighting against a common British enemy. The document that emerged from under Jefferson’s hand, clearly stating that “these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States,” was an engraved invitation to Spain and France, asking them to go to war alongside the Americans. The document was approved by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, a Thursday, printed by the next day, and immediately dispatched on a Continental Navy brig to Europe the following Monday. This document became known, of course, as the Declaration of Independence.

Americans therefore celebrate the July 4th holiday under somewhat false pretenses. The standard account regarding the Declaration of Independence goes something like this: The colonists could no longer tolerate the British government passing unjust laws and levying taxes without allowing proper representation. The Second Continental Congress voted to write a document explaining to King George III why they needed to be independent, and to justify to the American colonists and the world the reasons for revolting against the Crown.

Nothing could be further from the truth. The Declaration was not meant for King George III. The British monarch had already gotten the message, as he told Parliament in a speech on October 26, 1775, that the rebellion “is manifestly carried on for the purpose of establishing an independent empire.” Nor was it primarily intended to rally the American colonists to the cause of independence, as they had already instructed their delegates to vote for separation in the first place. The very idea of a document to formally declare independence was unprecedented; no previous nation that had rebelled against its mother country, as the Netherlands did against Spain more than a century earlier, needed to announce its intentions in written form.

Americans knew that Spain and France had long been spoiling for a rematch with Great Britain. They had come out badly in the Seven Years’ War against Britain, which ended in 1763 with France losing Canada and its central political position in Europe and with Spain giving up Florida and its dominance over the Gulf of Mexico. France wanted to regain its political clout, while Spain needed to defend its Latin American colonies. Both nations saw American independence as a means of weakening British domination in Europe and overseas.

Spain and France already had been secretly providing arms and clothing to the rebellious American colonies. Even before Lexington and Concord, government-backed merchants, like Diego de Gardoqui from Bilbao, had been assiduously trading European blankets, gunpowder, and muskets for American tobacco, whale oil, and cod. But blankets and muskets alone would never be enough against the British onslaught; in order to survive, America needed the full military might of Spain and France at its side.

The connection between a written declaration of independence and an American alliance with Spain and France had been publicly introduced in January 1776 in Thomas Paine’s smash bestseller, Common Sense. Voicing the sentiments of many American leaders, he exhorted his newly adopted countrymen, “Every thing that is right or natural pleads for separation. . . . ’TIS TIME TO PART.” He then went on to argue that “nothing can settle our affairs so expeditiously as an open and determined declaration for independence. . . . [neither] France or Spain will give us any kind of assistance . . . while we profess ourselves the subjects of Britain . . . The custom of all courts is against us, and will be so, until by an independence we take rank with other nations.”

The effect of Paine’s words was almost immediate. Within a few weeks of the publication, colonial leaders like Richard Henry Lee and Samuel Adams began taking up the call to formally declare independence from Britain with the express purpose of enlisting the help of Spain and France. Even John Adams, normally wary of any foreign entanglements, admitted that “we should be driven to the necessity of declaring ourselves independent states, and . . . employed in preparing . . . treaties to be proposed to foreign powers particularly to France and Spain . . . We were distressed for want of artillery, arms, ammunition, clothing.”[3]

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee stood before the Continental Congress and proclaimed the following motion: “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States . . . That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances.” While Congress debated Lee’s resolution, a small committee was formed to draft the declaration. Thomas Jefferson was chosen as its primary author. With little direction from Congress or time to spare, Jefferson’s great genius was to transform the original call for a distress signal into one of the most remarkable documents of Enlightenment thinking, arguing the case for independence based upon principles of freedom, equality, and natural rights.

The text that was finally voted on, after weeks of writing and rewriting, explained why the Americans wished to separate from Britain. As Jefferson asserted, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” The British monarch had not lived up to these ideals, Jefferson argued, and subjected the American colonies to a long list of abuses. For these reasons, America had shed its allegiance to the Crown and was now an independent nation.

The text that was finally voted on, after weeks of writing and rewriting, explained why the Americans wished to separate from Britain. As Jefferson asserted, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” The British monarch had not lived up to these ideals, Jefferson argued, and subjected the American colonies to a long list of abuses. For these reasons, America had shed its allegiance to the Crown and was now an independent nation.

At the very end of the document came the message that the kings of Spain and France would have taken notice of: “And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.” In other words: “We have staked everything on winning this war with Britain.” Unspoken was the plea: “Now please come to our aid.”

And so they did. Within a year, France signed treaties with the fledgling American nation, automatically bringing it into war against Britain. A year after that, Spain joined France in the fight, and though it never formally allied with the Americans, the Spanish crown declared that it would not “lay down its arms until the independence [of the United States] is recognized by the King of Great Britain.”[4] Together Spain and France turned a local war into a world war, which bled off British forces from America. Two years later, Bernardo de Gálvez’s Spanish troops wrested Florida from Britain, and French troops under Rochambeau fought shoulder-to-shoulder with Americans at Yorktown, effectively ending the conflict.

The Declaration of Independence therefore marks the United States as a nation that was created as part of an international partnership that fought together against a common adversary. As we are today interconnected across the planet in ways unimaginable to the Founding Fathers, each Fourth of July we must remember those roots and recommit ourselves as the indispensible nation in the global fight against common threats.

Larrie D. Ferreiro received his PhD in the History of Science and Technology from Imperial College London. He teaches history and engineering at George Mason University, Georgetown University, and the Stevens Institute of Technology. He is the author of Brothers at Arms: American Independence and the Men of France and Spain Who Saved It (Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in History.

[1] Instructions to Delegates for Charlotte County, Virginia, at a meeting of the Committee of Charlotte County, April 23, 1776; the “Halifax Resolves,” passed by the Fourth Provincial Congress of North Carolina at Halifax, North Carolina, April 12, 1776.

[2] Benjamin Franklin to Joseph Priestley, Paris, January 27, 1777, in Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-23-02-0150.

[3] From the Autobiography of John Adams [In Congress, Fall 1775–Spring 1776], in Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0027.

[4] Treaty of Aranjuez, April 12, 1779.