Spain’s Black Militias in the American Revolution

by Jane Landers

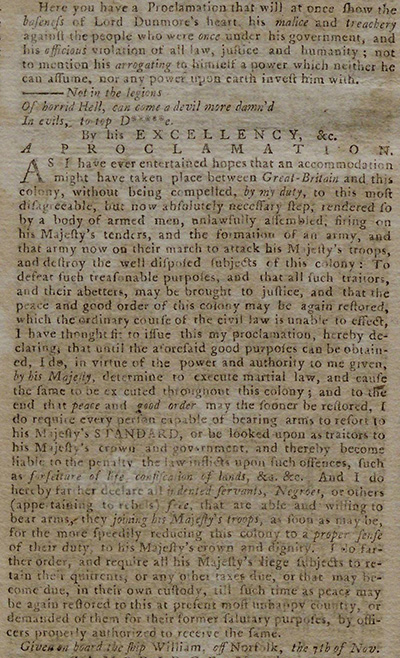

In 1775, Virginia’s governor, John Murray, Earl of Dunmore, issued a proclamation offering liberty to all enslaved Blacks who would join Great Britain’s military forces and defeat the rebellious Americans fighting for their independence. In doing so, he followed a long-established Spanish model of Black military service, both free and enslaved. The story of Great Britain’s Black Loyalists and their eventual diaspora to Nova Scotia, the Bahamas, London, and Sierra Leone has received considerable attention, but less popular attention has focused on the Black troops Spain deployed in the Lower South during the American Revolution. In fact, Africans and their descendants had enjoyed centuries of freedom and military service in the Spanish Americas before the Age of Revolutions transformed the world. This long history helps explain why some Africans and their descendants in the Spanish Empire chose royalism over revolution when the time came.

In 1775, Virginia’s governor, John Murray, Earl of Dunmore, issued a proclamation offering liberty to all enslaved Blacks who would join Great Britain’s military forces and defeat the rebellious Americans fighting for their independence. In doing so, he followed a long-established Spanish model of Black military service, both free and enslaved. The story of Great Britain’s Black Loyalists and their eventual diaspora to Nova Scotia, the Bahamas, London, and Sierra Leone has received considerable attention, but less popular attention has focused on the Black troops Spain deployed in the Lower South during the American Revolution. In fact, Africans and their descendants had enjoyed centuries of freedom and military service in the Spanish Americas before the Age of Revolutions transformed the world. This long history helps explain why some Africans and their descendants in the Spanish Empire chose royalism over revolution when the time came.

As Spanish conquerors and their African allies marched across the Caribbean and North and South America in the sixteenth century, they spread devastating diseases among Indigenous populations. The catastrophic collapse of Native populations left Spain largely dependent upon Africans and their descendants who built, serviced, and defended Spanish cities, grew critical foodstuffs and export crops, and labored on Spain’s earliest mines, ranches, and plantations.

The shortage of Indigenous and Spanish manpower also left Spain dependent upon Black military force. This was especially true in the circum-Caribbean where enslaved people and formerly enslaved people helped Spain maintain a tenuous control over thinly populated and greatly dispersed colonies under almost constant foreign attack and encroachment. Much of Spain’s imperial expanse was an undermanned frontier and, there, every hand counted. The Crown recognized as much and encouraged Black military service to defend its vast empire.

In the face of escalating foreign threats in the circum-Caribbean, the King ordered the Viceroy of New Spain to evaluate the formation of free Black companies such as those already defending his circum-Caribbean realms. He noted that those Black militias were “persons of valor” who fought with “vigor and reputation.”[1] By the mid-seventeenth century, then, the Spanish Crown had fully accepted that free men of color could be brave and honorable, and this important metropolitan acknowledgment encouraged additional enlistments. A Central American roster from 1673 listed almost two thousand pardos (usually meaning mulattoes, but sometimes referring to non-Europeans of mixed ancestry) serving in infantry units throughout the isthmus. Units of free Black or moreno men were also organized in Hispaniola, Vera Cruz, Campeche, Puerto Rico, Panama, Caracas, Cartagena, and Florida.

With the death of the last Hapsburg king, Carlos II, the Spanish throne was left empty and European powers competed for control of Spain’s vast empire. At the conclusion of the War of Spanish Succession (1700–1713), Bourbon Reformers acquired the Spanish Crown and, among other reforms, created formal “disciplined” Black militias across the Atlantic. Military men of African descent, who had already served Spain for more than two centuries, now elected their own officers and designed their unit’s uniforms. More importantly, they received the fuero militar, a corporate charter that exempted them from tribute and prosecution in civilian courts and granted them equal juridical status with White militiamen. The fuero also granted Black soldiers military, hospitalization, retirement, and death benefits, all major protections never before available to them. Formal membership in the military corporation also granted these men and their families higher status in a status-obsessed world. Men of African descent across Spain’s Atlantic holdings clearly appreciated the juridical and social benefits of militia membership and they developed traditions of multi-generational service. The military service of free men of color also redounded to the benefit of their wives and children who could inherit pensions and property, as well as a certain social status, from their husbands and fathers.

Despite enjoying relative privileges and opportunities not afforded in other European colonies, Africans and their descendants in Spain’s colonies were forced to choose sides when revolutionary movements swept the Atlantic. Some took up the new political ideologies of emancipation for all, while others remained committed royalists. It is not surprising that many Blacks adopted a royalist position, ardently supporting in word and deed the monarchs who freed, rewarded, and honored them. And Spain needed every hand it could during the seemingly endless wars of the eighteenth century.

Spain’s original claim to the Lower South, “la Florida,” stretched from the Florida Keys to Newfoundland and west to “the mines of Mexico.” But Spanish presence in the region was sparse and Spain’s vast territorial claim was challenged not only by diverse Indigenous groups but also by its European competitors England and France. In the absence of effective Spanish settlement, English colonists settled Carolina in 1670, and France claimed Louisiana in 1682, holding it until 1763 when at the end of the Seven Years’ War it passed to Spain. When disaffected French colonists rose against their Spanish governor and drove him from his post in 1769, Cuba’s Black militias helped restore effective Spanish control of Louisiana.

In 1775 Britain’s American colonists launched the American Revolution, and in 1778 King Carlos III of Spain joined France in declaring war against the British. Cuba’s militias of color returned to the region to serve under Louisiana’s Spanish governor, Bernardo de Gálvez, in the Gulf campaigns at Mobile and Pensacola, and upriver at Manchac and Baton Rouge. Governor Gálvez also paid local enslaved men to join his forces or provide military support, and hundreds did. Gálvez’s mixed-race forces took Baton Rouge and Natchez in 1779, Mobile in 1780, and finally Pensacola in May 1781, recovering the Gulf Coast for Spain.

Among the Cuban militiamen of color who fought in the Florida campaigns and helped Americans win their independence was José Antonio Aponte. Aponte was a corporal in the Disciplined Battalion of Free Blacks in Havana whose grandfather, Captain Joaquín Aponte, and father, Nicolás Aponte, had fought to defend their homeland in the unexpected and shocking British seizure of Havana in 1762. Aponte and others in Spain’s Black militias later fought against the British in the Bahamas and also served on Spanish corsairing expeditions throughout the Caribbean, all the while gaining “geopolitical literacy.”

Gálvez acknowledged the “zeal and rectitude” and “dedication to the Royal service” of his Black troops and nominated a number of them for royal commendations. The Crown also acknowledged the importance of the Black troops’ contribution with silver medals and promotions. As Cuba’s Black troops fought for the Spanish monarch, and as they helped liberate British colonials, they gained acquaintance with the rhetoric of independence. The motto emblazoned on the flag of Cuba’s Black battalions, “Victory or Death,” nicely mirrored the sentiment expressed by Patrick Henry.

France also sent Black troops to fight in the American Revolution. In 1779 the Chasseurs-Voluntaires de Saint-Domingue left Le Cap to assist American Patriots in Savannah. Their service is acknowledged today by a sculpture in the city square. Meanwhile, in South Carolina, one of the bloodiest of the American theaters, enslaved men fought on both Patriot and Loyalist sides, hoping to gain their freedom through military service as their counterparts in Spanish colonies had. Some enslaved men in South Carolina fought alongside the famed “Swamp Fox,” Francis Marion, while others took up Dunmore’s offer to join the Loyalists and departed with them for London at war’s end. Others who survived the carnage in South Carolina ended up escaping across the southern border to claim religious sanctuary in Spanish Florida. Sadly, under pressure from the new American Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, Spain revoked its century-old religious sanctuary policy in 1790. The formerly enslaved people who had already benefitted from manumission, however, like their predecessors, joined Florida’s Black militia and defended Spain in subsequent conflicts, such as the War of 1812. But in 1821 the new American government acquired Florida, and Spain’s loyal Black troops evacuated to Cuba under its protection.

Jane Landers is the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Professor of History at Vanderbilt University. She is the author of Atlantic Creoles in the Age of Revolutions (Harvard University Press, 2010) and Black Society in Spanish Florida (University of Illinois Press, 1999), and the co-editor, with Barry M. Robinson, of Slaves, Subjects, and Subversives: Blacks in Colonial Latin America (University of New Mexico Press, 2006).

[1] Royal order to the Viceroy of New Spain, July 6, 1663, cited in Colección de documentos para la historia de la formación social de hispanoamérica, 1493–1810, ed. Richard Konetzke, 3 vols. (Madrid, 1953–1962), 3:510–11.