Diego de Gardoqui and the Beginnings of Spanish-American Diplomacy

by Elisa Vargas

Born into a prominent Basque family on November 12, 1735, in the province of Vizcaya, Spain, Diego de Gardoqui was a treasured son of Don José Ignacio Gardoqui y Azpegorta and his wife Maria Simona. Groomed to be a banker, he was sent to London to learn the trade and especially the language of the economic philosopher Adam Smith. Diego became fluent in English, an attribute that was rare among Spaniards of his day and that would soon come in handy. In 1765, the patriarch of the family passed away, leaving Doña Maria Simona in charge of one of the largest codfish trading companies in the region, Gardoqui and Sons of Bilbao. True to the father’s wishes, Diego’s mother and siblings continued to support his career by buying him a post at the Bilbao consulate, which he would hold from 1771 to 1776, and launching his professional career in the public sector. In 1777, Diego was appointed as an advisor to the Court in Madrid and was suddenly called to channel secret aid to the thirteen colonies in America through his family’s business.

The origins of this clandestine plan are rather foggy. We know that there was a secret meeting between the Marquis de Grimaldi, former minister of state, in the city of Burgos with Arthur Lee, an American delegate sent from the Congress of the United States to seek foreign aid, both financial and logistical, for the revolutionary cause. Grimaldi was on his way to Rome as Spain’s newly appointed ambassador when he was called upon to meet with Lee as far away from the Court in Madrid as could be so that no one would know of Spain’s involvement in the cause and Great Britain would not catch wind. Gardoqui was present at the meeting, perhaps taking notes and without a doubt translating most of what was said, but most importantly, offering the perfect cover for Spain. It was well known that for more than two decades, the firm of Gardoqui and Sons had established commercial routes between Bilbao and Salem, Newburyport, Beverly, Boston, and Gloucester with American merchants, including Elbridge and Samuel Russell Gerry, soon to be commissioned by the second Continental Congress to supply the rebel army.

What we do know for certain is taken from Lee’s statement to Congress a few months later, when he noted that Spain was to send cloth (blue wool for the Continental uniforms, white fabric for shirts, buttons, socks, and boots), tents, blankets, anchors, ropes, and sails, among other naval equipment. Spain would also open a secret line of credit worth four million reales de vellón (equivalent to half a million Continental dollars). The goods would come straight from Bilbao by way of Gardoqui and Sons, which was in charge of hiring the boats and the crews and surveilling the precious consignment until its arrival in New Orleans through Havana. Havana’s governor, Bernardo de Gálvez, would then add ammunition and other supplies to the rebel army’s cache. Once complete, the cargo was authorized for pickup in Spanish ports by the rebel army.

In the first years of the Revolution, Gardoqui had an essential role in keeping the Continental Army supplied. Some would argue that Spanish blankets, tents, boots, and uniforms kept hundreds of Continental soldiers from dying at Valley Forge during the harsh winter of 1777. Be that as it may, the fact is that an intricate network of spies, agents, and allies would ensure the prompt collection and distribution of the cargo even after the closure of the East Coast ports by the British to the Mississippi River, enabling Washington’s troops to live another day.

With the entry of Spain into the war against Britain in 1779, the aid would arrive less discreetly. Keen to maintain the family business, Gardoqui undertook most of his commercial activities as a way to increase his capital. Codfish exports alone could produce as much as five million dollars annually. As previously noted, the company had been commercially active with the rebels well before the Liberty Bell rang, and not precisely selling textiles. Sources say that Gardoqui and Sons had exported in 1775 “300 hundred Muskets & Bayonetts, & about double the number of Pairs of Pistols”[1]. From 1765 to 1778, with the unintentional help of Madrid, the company had increased its capital exponentially with the import of goods such as tobacco and indigo from the colonies, in return for the expected military cache.

In 1783 the Crown asked Gardoqui to “settle pending negotiations with the new republic”[2] as Spain’s official envoy. A reasonable choice, as the don who delivered secret aid to the Continental Army personally knew not only George Washington but also Secretary of State John Jay and other prominent figures in Congress, including the Lee brothers and James Monroe. Gardoqui had become a key figure in negotiating the terms for Spain’s transatlantic commercial rights in North America, its navigation rights over the Mississippi River, and the definition of the borders in the south and west of the new nation. By the time Gardoqui arrived in the States, Richard Henry Lee, a supporter of Spain’s control of navigation along the Mississippi, was the president of Congress.

After independence, however, the amity between Spain and the United States was put to the test by Great Britain, which left a poisoned treaty for the former allies in 1783. Again, the two main issues were the navigation rights over the Mississippi and the definition of the southern and western borders of the new nation, mainly Parallel 31, located just north of the city of New Orleans. Since Spain was not an official ally of the US, it did not participate in the Paris negotiations and was therefore unaware of any territorial cessions. The British disregarded the 1781 capitulation of General John Campbell to Bernardo de Gálvez at the Battle of Pensacola while Spain disregarded the practice of international law, which ensured that navigation rights and borders could be transferred from one nation to another, in this case from France to Great Britain, and then from Great Britain to the United States.

After independence, however, the amity between Spain and the United States was put to the test by Great Britain, which left a poisoned treaty for the former allies in 1783. Again, the two main issues were the navigation rights over the Mississippi and the definition of the southern and western borders of the new nation, mainly Parallel 31, located just north of the city of New Orleans. Since Spain was not an official ally of the US, it did not participate in the Paris negotiations and was therefore unaware of any territorial cessions. The British disregarded the 1781 capitulation of General John Campbell to Bernardo de Gálvez at the Battle of Pensacola while Spain disregarded the practice of international law, which ensured that navigation rights and borders could be transferred from one nation to another, in this case from France to Great Britain, and then from Great Britain to the United States.

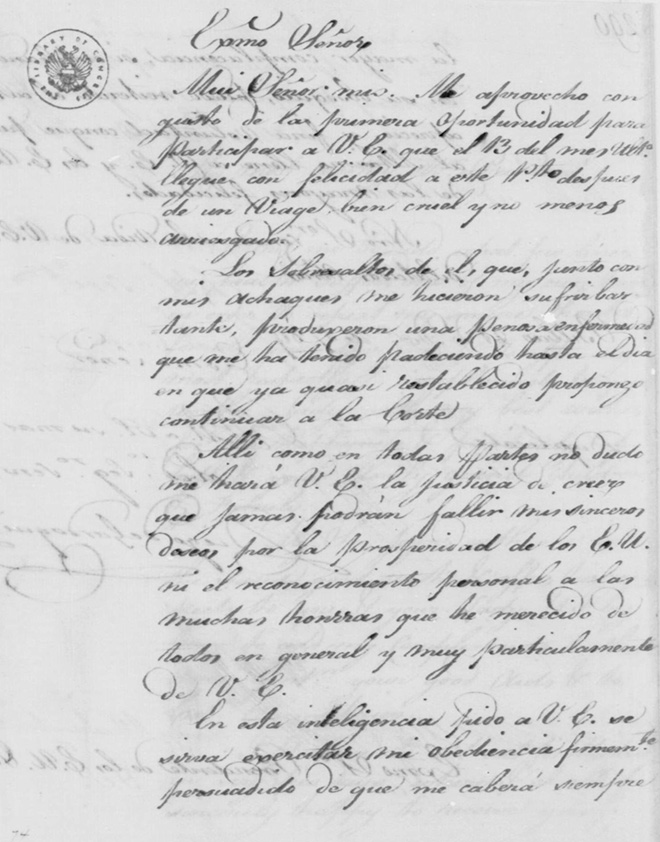

This issue would not only exceed Gardoqui’s diplomatic abilities, but would destroy John Jay’s promising career as foreign affairs secretary when in 1786 he submitted to the American Congress a principle of agreement between both countries that did not include access to the Mississippi. According to a letter sent by James Madison to George Washington in 1788, some southern congressmen accused Jay of relinquishing their rights to the Mississippi in exchange for commercial concessions from Spain, contravening his instructions and even keeping vital information from the legislative branch. The scandal wrecked any diplomatic opportunity to argue in favor of Spain’s claims. Gardoqui tried fruitlessly for years to gain political support from President Washington, through a failed gift diplomacy that included three volumes of Don Quixote and a pair of donkeys. Finally, in 1789, frustrated and defeated, Gardoqui returned to Spain. He was appointed as the new treasury secretary. On October 27, 1795, the United States and Spain signed the San Lorenzo Treaty, in which Spain acceded to each and every one of its counterpart’s aspirations. The border was established in the 31st parallel and the Mississippi was opened to American merchants. Don Diego de Gardoqui died on November 12, 1798, while serving in Turin, Italy, as a Spanish diplomat.

FURTHER READING

Armillas Vicente, José Antonio. “Ayuda secreta y deuda oculta: España y la independencia de los Estados Unidos,” in Eduardo Garrigues, Emma Sánchez Montañés, Sylvia L. Hilton, Almudena Hernández Ruigómez, and Isabel García-Montón Garrigues, eds., Norteamérica a finales del siglo XVIII: España y los Estados Unidos. Madrid: Fundación Consejo España-Estados Unidos y Marcial Pons (2008), pp. 171–196.

Calderón Cuadrado, Reyes. “Alianzas comerciales hispano-norteamericanas en la financiación del proceso de independencia de los Estados Unidos de América: La Casa Gardoqui e hijos,” in Eduardo Garrigues, Emma Sánchez Montañés, Sylvia L. Hilton, Almudena Hernández Ruigómez and Isabel García-Montón Garrigues, eds., Norteamérica a finales del siglo XVIII: España y los Estados Unidos. Madrid: Fundación Consejo España-Estados Unidos y Marcial Pons (2008), pp. 197–218.

Cava, María Jesús, and Begoña Cava. Diego María de Gardoqui: Un Bilbaíno en la diplomacia del siglo XVIII. Bilbao: BBK, 1992.

Chaparro Sainz, Álvaro. “Diego María de Gardoqui y los Estados Unidos: Actuaciones, influencias y relaciones de un vasco en el nacimiento de una nación.” Vasconia 39 (2013): 101–140.

Letters by George Washington, Diego de Gardoqui, and John Jay, Founders Online, National Archives, Washington, DC, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington.

Hernandez Andreu, Juan. “Diego Maria de Gardoqui y Arriquibar.” Real Academia de la Historia, Diccionario Biografico Electronico. http://dbe.rah.es/biografias/14269/diego- maria-de-gardoqui-y-arriquibar.

Qunitero Saravia, Gonzalo M. Bernardo de Gálvez: Spanish Hero of the American Revolution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Rueda, Natividad. La Compañía Comercial Gardoqui e hijos: 1760–1800. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Gobierno Vasco, 1992.

Saiz Valdivieso, Alfonso Carlos. Diego María Gardoqui. Esplendor y Penumbra. Madrid: Muelle Uritarte Editores, 2014.

Elisa Vargas, PhD, is a former fellow of the Fred W. Smith Library in Mount Vernon and the Preventive Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution Program of the Department of State, Washington, DC. She has served as an advisor for the presidency of Colombia and as a lecturer in the Johns Hopkins Program for Latin American Studies.

[1] Gardoqui and Sons to Jeremiah Lee, Bilbao, February 15, 1775, in Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1964), 1: 401.

[2] María Jesús Cava and Begoña Cava, Diego María de Gardoqui: Un Bilbaíno en la diplomacia del siglo XVIII (Bilbao: BBK, 1992), 28–29.