From the Editor

In this issue, our scholars have taken on the difficult task of examining America’s immigration policies across the centuries. From their essays we learn that modern debates over exclusion, restriction, and deportation are not new; they are part of a long history of this country’s effort to confront a reality: America is the desired destination of people from across the globe. These essays take a close look at the historical circumstances that prompted an era’s immigration laws—and that impelled later eras to revise them. Taken together, they provide us with the broadest, and most compelling, perspective on “e pluribus unum.”

In her overview essay, “The History of US Immigration Laws: What Students Should Know,” Jane Hong focuses on how best to teach this complicated but important subject to students across the country. Hong recounts her experience working with California teachers and shares with us the four key lessons she learned: it is important to pay attention to regional and state differences in talking about who is an immigrant; it is equally important to examine state and local laws as it is to consider federal immigration restrictions; it is critical to acknowledge the active resistance of immigrants to restrictions; and it is essential to trace the connection between past immigration policies and debates to our modern debate on these issues.

In her overview essay, “The History of US Immigration Laws: What Students Should Know,” Jane Hong focuses on how best to teach this complicated but important subject to students across the country. Hong recounts her experience working with California teachers and shares with us the four key lessons she learned: it is important to pay attention to regional and state differences in talking about who is an immigrant; it is equally important to examine state and local laws as it is to consider federal immigration restrictions; it is critical to acknowledge the active resistance of immigrants to restrictions; and it is essential to trace the connection between past immigration policies and debates to our modern debate on these issues.

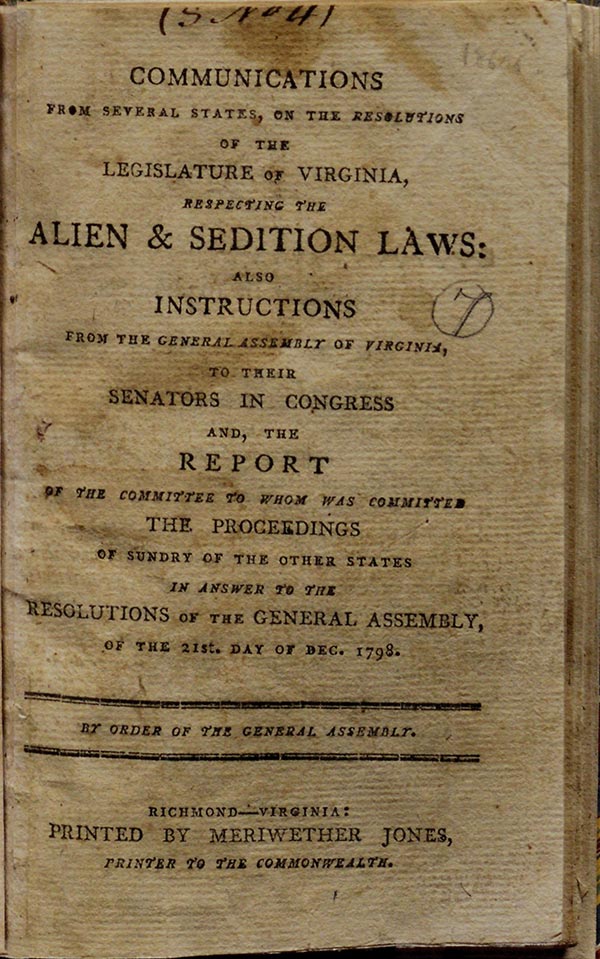

In her essay, “Immigrants and the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798,” Terri Halperin provides the background for the Federalist Congress’s passage of a stringent naturalization act and two Alien Acts that gave President John Adams discretion to deport or imprison “dangerous” noncitizens. Although Adams never employed this power, many French and Irish political radicals, anxious about their fate, voluntarily departed. The Sedition Act of that same year, Halperin notes, also targeted immigrants, particularly editors of pro-Jeffersonian party newspapers.

In her essay, “Immigrants and the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798,” Terri Halperin provides the background for the Federalist Congress’s passage of a stringent naturalization act and two Alien Acts that gave President John Adams discretion to deport or imprison “dangerous” noncitizens. Although Adams never employed this power, many French and Irish political radicals, anxious about their fate, voluntarily departed. The Sedition Act of that same year, Halperin notes, also targeted immigrants, particularly editors of pro-Jeffersonian party newspapers.

![“Emigrants leaving Queenstown [Ireland] for New York,” Harper’s Weekly, September 26, 1874 (Library of Congress) “Emigrants leaving Queenstown [Ireland] for New York,” Harper’s Weekly, September 26, 1874 (Library of Congress)](/sites/default/files/3c05528u.jpg) Hidetaka Hirota takes a closer look at discrimination against poor immigrants in his essay, “Expelling the Poor: The Antebellum Origins of American Deportation Policy.” Observing that the issue is very much alive today, Hirota reminds us that “expelling foreigners” is a policy deeply rooted in the nation’s past. He cites the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which allowed the deportation of Chinese laborers, but notes that, in earlier years, the US government and local and state governments had used poor laws to exclude and deport indigent immigrants. Irish Catholics were targets when the Irish famine drove many to America, and criticism of these men and women—as “Lazy, Ungrateful, Lying and Thieving”—is echoed, Hirota notes, in anti-immigrant rhetoric today.

Hidetaka Hirota takes a closer look at discrimination against poor immigrants in his essay, “Expelling the Poor: The Antebellum Origins of American Deportation Policy.” Observing that the issue is very much alive today, Hirota reminds us that “expelling foreigners” is a policy deeply rooted in the nation’s past. He cites the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which allowed the deportation of Chinese laborers, but notes that, in earlier years, the US government and local and state governments had used poor laws to exclude and deport indigent immigrants. Irish Catholics were targets when the Irish famine drove many to America, and criticism of these men and women—as “Lazy, Ungrateful, Lying and Thieving”—is echoed, Hirota notes, in anti-immigrant rhetoric today.

Robert Zeidel reminds us of the often overlooked but critically important background to the 1917 Literacy Test Act and the 1921 Quota Act. In his examination of “The Dillingham Commission and the ‘Immigration Question,’ 1907−1921,” Zeidel looks at the changing context produced by industrialization and the resulting rise in xenophobia among lawmakers. In 1907, Congress created the Dillingham Commission, a nine-member investigatory commission made up of academics in political economy, anthropology, and other social sciences. Literacy test proponents and lawmakers who supported immigration quotas used—and misused—the commission’s findings to gain their ends. Congress increased the restrictions on new immigrants, denying any quotas to Asians, in 1921.

Robert Zeidel reminds us of the often overlooked but critically important background to the 1917 Literacy Test Act and the 1921 Quota Act. In his examination of “The Dillingham Commission and the ‘Immigration Question,’ 1907−1921,” Zeidel looks at the changing context produced by industrialization and the resulting rise in xenophobia among lawmakers. In 1907, Congress created the Dillingham Commission, a nine-member investigatory commission made up of academics in political economy, anthropology, and other social sciences. Literacy test proponents and lawmakers who supported immigration quotas used—and misused—the commission’s findings to gain their ends. Congress increased the restrictions on new immigrants, denying any quotas to Asians, in 1921.

Maddalena Marinari describes the political battle over immigration policy during the Cold War era in her essay, “‘In the Name of America’s Future’: The Fraught Passage of the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act.” To combat the reforms that had gone far toward repealing many exclusion acts, Senator Patrick McCarran of Nevada proposed a bill to tighten exclusion, deportation, and naturalization regulations. Reformers struck back with a liberal omnibus bill—and the battle was on. McCarran won the struggle but his victory in Congress suffered a setback when his bill was vetoed by President Harry S. Truman. Congress responded by overriding that veto. But, as Marinari explains, the force of the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act was weakened as immigration figures soared and reformers pushed through special legislation for refugees, orphans, and others. In the end, a gradual shift to immigrants from non-European countries paved the way for the demographic changes political leaders like McCarran dreaded.

Maddalena Marinari describes the political battle over immigration policy during the Cold War era in her essay, “‘In the Name of America’s Future’: The Fraught Passage of the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act.” To combat the reforms that had gone far toward repealing many exclusion acts, Senator Patrick McCarran of Nevada proposed a bill to tighten exclusion, deportation, and naturalization regulations. Reformers struck back with a liberal omnibus bill—and the battle was on. McCarran won the struggle but his victory in Congress suffered a setback when his bill was vetoed by President Harry S. Truman. Congress responded by overriding that veto. But, as Marinari explains, the force of the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act was weakened as immigration figures soared and reformers pushed through special legislation for refugees, orphans, and others. In the end, a gradual shift to immigrants from non-European countries paved the way for the demographic changes political leaders like McCarran dreaded.

Tom Gjelten traces the long history of immigration regulation policy leading up to the 1960s in his essay “The 1965 Immigration Act: Opening the Nation to Immigrants of Color.” He reminds us that the first restriction on immigration was passed in 1790, one year after the Constitution was ratified. The act restricted US citizenship to free whites. In the nineteenth century, immigration from Asia and southern and eastern Europe was seen as a threat to America’s white Anglo-Saxon character. This xenophobia continued into the twentieth century as almost a million immigrants arrived each year. National origins quotas were designed to restrict immigration from these areas and were not lifted until the civil rights era. Gjelten details the politics of the passage of the 1965 Immigration Act which produced a demographic transformation and sparked a renewed controversy over who could be an American.

Tom Gjelten traces the long history of immigration regulation policy leading up to the 1960s in his essay “The 1965 Immigration Act: Opening the Nation to Immigrants of Color.” He reminds us that the first restriction on immigration was passed in 1790, one year after the Constitution was ratified. The act restricted US citizenship to free whites. In the nineteenth century, immigration from Asia and southern and eastern Europe was seen as a threat to America’s white Anglo-Saxon character. This xenophobia continued into the twentieth century as almost a million immigrants arrived each year. National origins quotas were designed to restrict immigration from these areas and were not lifted until the civil rights era. Gjelten details the politics of the passage of the 1965 Immigration Act which produced a demographic transformation and sparked a renewed controversy over who could be an American.

In his analysis of “Immigration Policy, Mexican Americans, and Undocumented Immigrants, 1954 to the Present,” Eladio Bobadilla looks at the history of Mexican American opposition to undocumented immigrants during the 1950s and the causes of their growing support for these immigrants by the 1980s. In the 1950s, Mexican American organizations supported Operation Wetback, a policy of mass deportation. They were also critical of the Bracero Program that imported some five million men as workers between 1942 and 1964. Leaders like Cesar Chavez of the United Farm Workers union sought to keep Mexican immigrants out of the country. But the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and President Jimmy Carter’s commission on immigration ultimately led to the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, and by then most Mexican Americans favored the protection of undocumented immigrants. They opposed California’s efforts to deny public services to these immigrants in 1994 and today, they support what Bobadilla calls a new civil rights movement.

In his analysis of “Immigration Policy, Mexican Americans, and Undocumented Immigrants, 1954 to the Present,” Eladio Bobadilla looks at the history of Mexican American opposition to undocumented immigrants during the 1950s and the causes of their growing support for these immigrants by the 1980s. In the 1950s, Mexican American organizations supported Operation Wetback, a policy of mass deportation. They were also critical of the Bracero Program that imported some five million men as workers between 1942 and 1964. Leaders like Cesar Chavez of the United Farm Workers union sought to keep Mexican immigrants out of the country. But the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and President Jimmy Carter’s commission on immigration ultimately led to the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, and by then most Mexican Americans favored the protection of undocumented immigrants. They opposed California’s efforts to deny public services to these immigrants in 1994 and today, they support what Bobadilla calls a new civil rights movement.

This issue of History Now is especially rich in special features that complement the seven essays. Chief among these is a digital timeline, “US Immigration since 1850: A Statistical and Visual Timeline.” Based in large part on Immigration: An American Story, a newly published Gilder Lehrman traveling panel exhibition funded by the Stuart Foundation, the “US Immigration since 1850” timeline focuses on the overall scale and nature of immigration over a period of nearly 170 years, addressing why so many sought to come to the United States from so many nations across the globe. The issue’s other highlights include a lesson plan by 2009 National History Teacher of the Year award winner and the Gilder Lehrman director of education, Tim Bailey. You will also find videos on topics such as Angel Island and early and later years of European immigration, and links to a host of earlier History Now essays by noted scholars, including Ned Blackhawk, Hasia Diner, Thomas Kessner and Phillip Lopate. Finally, we offer a “Spotlight on Primary Sources,” each drawn from the vast Gilder Lehrman Collection, that will help you make the past come alive in your classroom.

Our best wishes to all of you now that the school year is underway—and our hopes that this issue, like every issue of History Now, will provide you and your students with a deeper and more complex understanding of our national past.

Carol Berkin, Editor

Nicole Seary, Associate Editor

Related Resources

Other Features

From the Teacher’s Desk

“Late 19th- and Early 20th-Century Immigration: History through Art and Documents” by Tim Bailey

Online Exhibition

US Immigration since 1850: A Statistical and Visual Timeline

From the Archives

Issues of History Now

Immigration: History Now 3 (Spring 2005)

Essays

“The Development of the West” by Ned Blackhawk

“Coming to America: Ellis Island and New York City” by Vincent J. Cannato (American Cities: History Now 11 (Spring 2007))

“‘The New Colossus’: Emma Lazarus and the Immigrant Experience” by Julie Des Jardins (American Poets, American History: History Now 39 (Spring 2014)

“Immigration and Migration” by Hasia Diner

“History Times: A Nation of Immigrants,” essay from American History: An Introduction, a volume of the History in a Box series published by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, 2009

Spotlights on Primary Sources

Verses on Norwegian emigration to America, 1953

San Francisco’s Chinatown, 1880

Literacy and the immigration of “undesirables,” 1903

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, 1911

Preventing labor discrimination during World War II, 1942

Videos

“The Quest for Equality: The Early Years of European Immigration” by Matthew Frye Jacobson, Yale University

“The Quest for Equality: Later European Immigration to the United States” by Matthew Frye Jacobson, Yale University

“Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America” by Erika Lee, University of Minnesota

“Immigration to the United States since 1965” by Mae Ngai, Columbia University

Lesson Plans

“Immigration in the Gilded Age: Using Photographs as Primary Sources” by Philip J. Nicolosi

“Framing Soo Hoo Lem Kong” by Kristal Cheek (Grades 6–8)