Immigrants and the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798

by Terri Diane Halperin

Americans were on edge in the spring and summer of 1798. War and revolution were raging in Europe; Ireland was rebelling against England; and France was continuing its attacks on American ships. Although the Jay Treaty, which went into effect in 1796, had eased tensions between the United States and England, sustained good relations were not guaranteed. France and Spain seemed to have schemes to expand or re-establish their empires on America’s western frontier, putting the integrity of US borders and territory at risk. In addition to these perceived dangers, there were significant numbers of immigrants arriving in the United States seeking refuge from the chaos of Europe. Some of the recent arrivals from France, Ireland, Scotland, and England were fleeing political persecution and hoped to find a safe haven for themselves and their ideas in America. Instead of welcoming these immigrants, many Americans believed that they put the nation in peril.

When Congress learned of the failure of the diplomatic mission to France in the XYZ Affair, the Federalist majority moved to shore up the nation’s defenses. They commissioned new naval ships to fight the Quasi-War against France and enlarged the army to prepare for a possible French invasion. They also moved to defend against perceived domestic enemies by passing the Alien and Sedition Acts.

When Congress learned of the failure of the diplomatic mission to France in the XYZ Affair, the Federalist majority moved to shore up the nation’s defenses. They commissioned new naval ships to fight the Quasi-War against France and enlarged the army to prepare for a possible French invasion. They also moved to defend against perceived domestic enemies by passing the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Federalists feared that constant criticism and agitation against the government would endanger the nation itself. In their view, one potential source of unrest was recently arrived immigrants who brought the chaotic politics and radical ideas of Europe to America and sought to indoctrinate Americans with their beliefs. When Federalists looked at France in particular, they saw a nation that had effected or threatened the collapse of European governments by fomenting discord from within; they believed immigrants and their American allies would do the same in America. One Federalist, Noah Webster, summed up the situation by saying that for every one well-behaved immigrant “we receive three or four discontented, factious men . . . hirelings of France, and disaffected offscourings of other nations.”[1] The danger to the nation felt very real.

Previously, most Americans had welcomed immigrants and believed that most white men were capable of becoming good republican citizens. However, as partisan rancor intensified during the 1790s, so did conflicts over immigration, with the Federalists becoming more nativist and Democratic-Republicans remaining more accommodating. Under the Naturalization Act of 1790, free, white, male aliens of good character who resided in the US for two years were eligible for citizenship. By mid-decade, with an influx of immigrants, a consensus had developed that two years was not long enough to learn to be a republican citizen. In 1795, the residency requirement was extended to five years, but what it meant to be a citizen did not change. Under the Constitution, citizenship was a shared responsibility between the federal government and the states. The federal government established general rules of naturalization, but the states determined the rights of citizenship—who could vote or serve in public office, for example. Both federal and state courts could issue certificates of naturalization. During the 1794−1795 debate, both Federalists and Democratic-Republicans began to express concerns that would become more fully articulated in 1798.

In 1798, the Federalist-controlled Congress passed a new naturalization law along with laws to deport suspicious or enemy aliens and combat seditious speech. The Naturalization Act of 1798 not only increased the residency requirement to fourteen years, but also created additional obstacles to becoming a citizen. Federalists made naturalization an exclusively federal responsibility by prohibiting state courts from participation. Aliens were required to register with federal officials, making enforcement of the Alien Enemies and Alien Friends laws easier. These laws gave the president discretion to deport any suspicious aliens without a trial or hearing. The Alien Enemies Act was only in effect when war was formally declared and only aliens from nations with which the US was at war could be deported. Since the US and France never formally declared war, this law was never invoked. Unlike the other laws, the Alien Enemies Act passed with Democratic-Republican support; it never expired and is still valid today.

Under the Alien Friends Act, the president could deport any alien whom he deemed suspicious. Although several men were watched, the government did not deport anyone for the two years the law was in effect. President John Adams repeatedly clashed with his secretary of state, Timothy Pickering, over enforcement.  When Pickering asked for signed, blank deportation orders, Adams refused. Adams favored a narrow interpretation of the law and doubted Pickering’s competence. Pickering did admit to neglecting the Alien Friends law because of other pressing business. In Pickering’s defense, however, he may have exercised some good judgment, particularly in the case of Georges-Henri Victor Collot, an expert French mapmaker who had been traveling through the American Southwest and Spanish Louisiana when the British military captured and paroled him to the US. Instead of deporting him, Pickering had Collot watched. It might have been prudent to keep Collot in the country rather than allow him to give valuable aid to the French government’s rumored quest to reestablish a North American empire. Collot eventually left on his own, as would many other Frenchmen. In fact, several ships carried hundreds of immigrants voluntarily back to France. Numerous others canceled their plans to emigrate. America no longer was a safe haven for immigrants.

When Pickering asked for signed, blank deportation orders, Adams refused. Adams favored a narrow interpretation of the law and doubted Pickering’s competence. Pickering did admit to neglecting the Alien Friends law because of other pressing business. In Pickering’s defense, however, he may have exercised some good judgment, particularly in the case of Georges-Henri Victor Collot, an expert French mapmaker who had been traveling through the American Southwest and Spanish Louisiana when the British military captured and paroled him to the US. Instead of deporting him, Pickering had Collot watched. It might have been prudent to keep Collot in the country rather than allow him to give valuable aid to the French government’s rumored quest to reestablish a North American empire. Collot eventually left on his own, as would many other Frenchmen. In fact, several ships carried hundreds of immigrants voluntarily back to France. Numerous others canceled their plans to emigrate. America no longer was a safe haven for immigrants.

Although the Sedition Act was the only one of the four laws to directly affect American citizens, it targeted immigrants as well. In fact, two of the law’s victims—the political philosopher Thomas Cooper, born and educated in England, and the newspaper editor James Callender, born in Scotland—became citizens, under the provisions of the 1795 law, to avoid possible deportation. Although they protected themselves against deportation, both were convicted of sedition and spent several months in jail.

Federalists went after one immigrant in particular—William Duane, an Irishman who took over the editorship of the Philadelphia Aurora after Benjamin Franklin Bache’s death. Federalists were determined, but failed again and again, to silence one of the most popular and vitriolic Democratic-Republican newspapers.  They charged Bache with sedition under common law before the Sedition Act passed, but Bache died in a yellow fever epidemic before his trial. With the help of Duane and others, Bache’s wife, Margaret Hartman Markoe Bache, continued to publish the Aurora.

They charged Bache with sedition under common law before the Sedition Act passed, but Bache died in a yellow fever epidemic before his trial. With the help of Duane and others, Bache’s wife, Margaret Hartman Markoe Bache, continued to publish the Aurora.

Duane posed a danger not only as a writer and printer but also as an organizer of immigrants. He led a Philadelphia militia company of Irish immigrants who Pickering feared would join the French if they invaded the US. In February 1799, Duane was among the organizers of a petition against the Alien Friends law. When they gathered outside of a Philadelphia church one Sunday to collect signatures, a confrontation resulted in which one of Duane’s allies drew a gun. Duane and others were charged with seditious riot. A jury acquitted them and rejected the prosecutor’s argument that aliens, since they were not citizens, did not possess the right of petition; the jurors thought the right was not a function of citizenship but possessed by all regardless of status.

Federalists were alert to the dangers Duane posed and twice more tried to silence him. Adams endorsed using both the Alien Friends and Sedition Acts against Duane. However, Duane claimed American citizenship since he had been born in  Vermont even though his family had returned to Ireland before the Revolution. Perhaps the ambiguity of his citizenship status prevented his deportation. The Federalists’ aim was not just to silence Duane but to silence the Aurora. Certainly, Pickering and Adams believed that the Aurora’s “uninterrupted stream of slander on the American government” constituted a strong case for sedition.[2] In August 1799, Duane was arrested. Specifically, he was indicted for accusing government officials of being under the undue influence of the British and accepting bribes from British agents. The law specified that defendants could use truth as a defense—if it was true, then it was not seditious. As most cases involved opinion and not discernable facts, truth, although often tried, was never successfully used as a defense. Duane, however, claimed that he possessed definitive proof of his allegations. After several postponements, the government withdrew the charges. Duane successfully used truth as his defense. Finally, the Senate attempted to charge him with contempt after he published an account of its secret proceedings. Duane managed to elude the Senate and continue printing the Aurora, of which he became publisher when he married Bache’s widow, Margaret, in 1800. Federalists failed to silence one of their most vocal critics.

Vermont even though his family had returned to Ireland before the Revolution. Perhaps the ambiguity of his citizenship status prevented his deportation. The Federalists’ aim was not just to silence Duane but to silence the Aurora. Certainly, Pickering and Adams believed that the Aurora’s “uninterrupted stream of slander on the American government” constituted a strong case for sedition.[2] In August 1799, Duane was arrested. Specifically, he was indicted for accusing government officials of being under the undue influence of the British and accepting bribes from British agents. The law specified that defendants could use truth as a defense—if it was true, then it was not seditious. As most cases involved opinion and not discernable facts, truth, although often tried, was never successfully used as a defense. Duane, however, claimed that he possessed definitive proof of his allegations. After several postponements, the government withdrew the charges. Duane successfully used truth as his defense. Finally, the Senate attempted to charge him with contempt after he published an account of its secret proceedings. Duane managed to elude the Senate and continue printing the Aurora, of which he became publisher when he married Bache’s widow, Margaret, in 1800. Federalists failed to silence one of their most vocal critics.

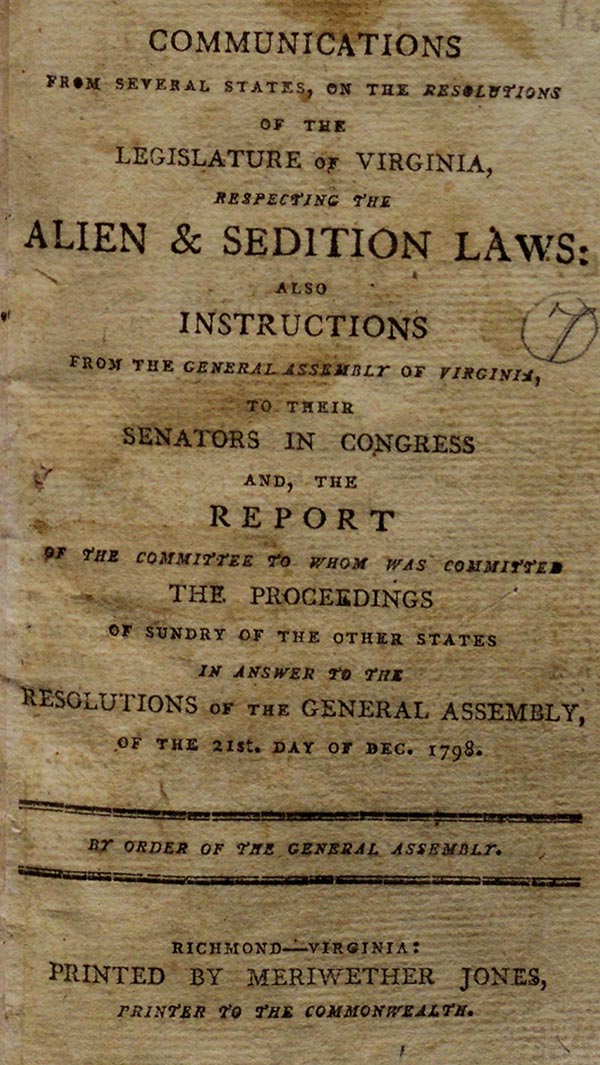

Protests did not just come from alien petitioners or defiant printers but also from state legislatures. The most famous resolutions came from Virginia and Kentucky and were drafted by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson respectively. After only recriminations from other states, Virginia and Kentucky responded—Kentucky with another set of resolutions in 1799 and Virginia with a lengthy defense by Madison, who was then a newly elected member of the Virginia legislature. The Report of 1800 was a vigorous vindication of free debate and of individual rights.[3] Madison argued that the Alien Friends law, as well as the Sedition Act, were unconstitutional and violated the principle of preventative justice. Madison argued that when they came to the United States, foreigners tacitly agreed to obey American laws, and that in return, they received the protections of the Constitution, which did not apply exclusively to citizens. While the Constitution granted broad powers to defend the nation, Madison explained, that did not include the power to prevent all unrest by deporting suspect foreigners or punishing all seditious speech; doing so would endanger people’s rights. Madison made the argument for protection of individual rights over the security of the nation.

With Jefferson’s electoral victory in 1800, the Federalist experiment came to an end. The Alien Friends and Sedition laws both expired and a new naturalization law in 1802 reverted to the 1795 standards. The issues of free speech, immigrant rights, or what it meant to be an American, however, were not settled. Americans would revisit these issues again and again.

[1] Noah Webster to Timothy Pickering, July 7, 1797, as quoted in John C. Miller, Crisis in Freedom: The Alien and Sedition Acts (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1951), 42.

[2] Timothy Pickering to John Adams, July 24, 1799, in Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1854), 9: 3.

[3] “The Report of 1800, [7 January] 1800,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified June 13, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-17-02-0202. [Original source: The Papers of James Madison, vol. 17, March 31, 1797–March 3, 1801, and supplement January 22, 1778–August 9, 1795, ed. David B. Mattern, J. C. A. Stagg, Jeanne K. Cross, and Susan Holbrook Perdue (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1991), 303–351.]

Terri Diane Halperin is a member of the history department at the University of Richmond. She is the author of The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798: Testing the Constitution (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).