The 1965 Immigration Act: Opening the Nation to Immigrants of Color

by Tom Gjelten

Americans might think their country has always been open to all, but until 1965 people who were not white or did not come from northern or western Europe were not welcomed as immigrants. Only with the passage that year of a new immigration law was the United States officially opened to people of all nationalities on a more or less equal basis. The law was hugely consequential. In the half century after its passage, the 1965 Immigration and Naturalization Act changed the face of America.

The hostility to immigrants of color dated from the earliest days of the republic. The first immigration law, passed in 1790, restricted US citizenship to free whites. Benjamin Franklin said the United States would benefit by excluding “all Blacks and Tawneys.”[1] Africans who arrived in chains were not citizens, and until 1866 neither were their African American descendants.

Beginning in the mid-1800s, tens of thousands of Chinese laborers came to the country to help build the transcontinental railroad, work on farms, or toil in factories, but under the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, they were banned from applying for naturalization as US citizens, and further migration from China was effectively prohibited.

Beginning in the mid-1800s, tens of thousands of Chinese laborers came to the country to help build the transcontinental railroad, work on farms, or toil in factories, but under the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, they were banned from applying for naturalization as US citizens, and further migration from China was effectively prohibited.

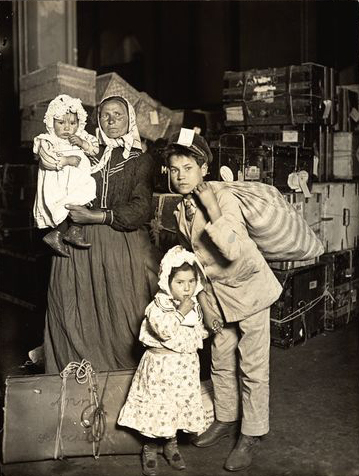

Such measures preserved America’s white Anglo-Saxon character for a while, but by the end of the nineteenth century new immigrants from southern and eastern Europe began arriving in greater numbers. They looked and dressed a bit different, and as their numbers grew they also encountered a wall of prejudice.

A Harvard-trained lawyer named Prescott Hall, co-founder of the Immigration Restriction League, gave voice to the white supremacist view in an 1897 article in the North American Review. “Do we want this country to be peopled by British, German, and Scandinavian stock—historically free, energetic, progressive,” Hall asked, “or by Slav, Latin, and Asiatic races—historically downtrodden, atavistic, and stagnant?”[2]

By 1905, about a million immigrants were arriving each year, including many Jews, Poles, Italians, and other ethnicities not well represented in earlier migrations. A government commission was established to consider new immigration policies, and in its 1911 report the commission recommended the establishment of immigrant quotas for each country, with preference given to those considered to have “desirable” populations.

By 1905, about a million immigrants were arriving each year, including many Jews, Poles, Italians, and other ethnicities not well represented in earlier migrations. A government commission was established to consider new immigration policies, and in its 1911 report the commission recommended the establishment of immigrant quotas for each country, with preference given to those considered to have “desirable” populations.

After much debate, the US Congress enacted the national origin quotas in 1924. The countries of northern and western Europe were allocated more than 140,000 immigrant slots each year, while those in southern and eastern Europe got just 20,000 slots, and all the countries of Asia and Africa combined were given barely 3,000 among them.

National origin quotas remained the basis for US immigration policy for more than forty years, despite their arguably racist character. The system was reaffirmed in 1952 with the passage of the McCarran-Walter Act. The quotas were adjusted slightly but they retained essential discriminatory features. A native-born British citizen, for example, who happened to have Asian parentage could not qualify for any of the 65,000 slots reserved for people from the United Kingdom and had to compete instead for one of the few slots set aside for his or her ancestral country. The same rule held true for all immigrant candidates with Asian ancestry. A presidential commission on immigration, having reviewed the quota system in the aftermath of the McCarran-Walter Act, called it “a challenge to the tradition that American law and its administration must be reasonable, fair, and humane.”[3]

The US Congress, however, was largely controlled by southern Democrats, many of whom clung to segregationist views. The forces in favor of replacing the national quota system with a new immigration law began to coalesce only with the election of John F. Kennedy in 1960. Kennedy made repeal of the national origin quota system a theme of his campaign, though he focused less on its anti-Asian and anti-African character than on its under-representation of Jews, Italians, and other peoples from southern and eastern Europe.

A decisive blow against the quota system came with the emergence of a powerful civil rights movement in the early 1960s and the growing awareness that discrimination of all kinds was a betrayal of American values and ideals. As president, Lyndon Johnson gave his full support to immigration reform, despite having voted as a US senator in 1952 to uphold the quota system.

In his first State of the Union address in January 1964, just two months after taking office, Johnson called on Congress to reject national origin quotas. “A nation that was built by the immigrants of all lands can ask those who now seek admission: ‘What can you do for our country?’” he said. “But we should not be asking, ‘In what country were you born?’”

With the passage later that year of the Civil Rights Act, the political conditions seemed finally set for the elimination of national origin quotas. The reform effort was led in the Senate by Democrat Phil Hart of Michigan and in the House by Democrat Emanuel Celler, who represented a racially diverse district in Brooklyn, New York. Celler was first elected to Congress in 1923, a year before national origin quotas were enacted, and over his four decades in office he had made elimination of the quota system one of his top legislative priorities.

The reform would not come, however, without struggle and compromise, as some powerful members of Congress opposed what they correctly saw as a reform that could transform the demographic character of the country. Representative Ovie Fisher, a conservative Democrat from Texas, said he objected to the proposed immigration bill because it “shifts the mainstream of immigration from western and northern Europe—the principal source of our present population—to Africa, Asia, and the Orient.”[4]

Democratic Ssenator Sam Ervin of North Carolina complained that “the people of Ethiopia have the same right to come to the United States under this bill as the people from England, the people of France, the people of Germany, [and] the people of Holland. . . . With all due respect to Ethiopia,” Ervin said, “I don’t know of any contributions that Ethiopia has made to the making of America.”[5]

For the new law to pass the House, it had to be approved by the immigration subcommittee of the House Judiciary Committee. Celler chaired the full committee, but the subcommittee was under the control of a Celler adversary, Democrat Michael Feighan of Cleveland, Ohio. Under pressure from President Johnson, Feighan ultimately agreed to allow the bill to move forward, but only after getting its supporters to agree to a compromise.

The original version of the Hart-Celler proposal, after eliminating the national origin quota system, called for prioritizing those immigrant candidates who had skills considered “especially advantageous” to the US economy and society. Feighan opposed that formula, arguing that priority be given instead to immigrants with family members already resident in America. His reasoning was that such a preference would mean most new immigrants would probably have the same northern and western European background as the existing US population, because Asian, African, and other candidates would be less likely to have relatives living in the US.

Groups like the American Legion, which had lobbied in favor of retaining national origin quotas, supported Feighan’s compromise, seeing his proposal as “a naturally operating national origin system,” in the words of two Legion representatives. “Nobody is quite so apt to be of the same national origin of our present citizens as are members of their immediate families,” they wrote, “and the great bulk of immigrants henceforth will . . . hail from the same parent countries as our present citizens.”[6]

Conversely, advocates for Asian immigration were dismayed by the Feighan proposal. The Japanese American Citizens League noted that Asians constituted just one half of one percent of the total US population, so the number of Asians who would qualify for immigrant visas under a family unification scheme would be small. “Thus,” the League complained, “it would seem that, although the immigration bill eliminated race as a matter of principle, in actual operation immigration will still be controlled by the now discredited national origins system.”[7]

Supporters of immigration reform were largely satisfied by the removal of the national origin quotas as a matter of principle, however, and they accepted the Feighan compromise.  As amended, the bill passed both houses of Congress by a large margin in September 1965 and was signed into law by President Johnson on October 3, 1965, in an elaborate ceremony at the base of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor. The large margin supporting the 1965 Act was due in part to the widespread belief that the elimination of the national origin quotas, aside from the moral victory it represented, would have little practical effect on the pattern of immigration in the coming years.

As amended, the bill passed both houses of Congress by a large margin in September 1965 and was signed into law by President Johnson on October 3, 1965, in an elaborate ceremony at the base of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor. The large margin supporting the 1965 Act was due in part to the widespread belief that the elimination of the national origin quotas, aside from the moral victory it represented, would have little practical effect on the pattern of immigration in the coming years.

“This bill that we will sign today is not a revolutionary bill,” Johnson said. “It does not affect the lives of millions.”[8] Indeed, change was slow in coming. Because few people from countries previously subject to restrictive quotas had family members in the United States, the elimination of the quotas initially made little difference.

Slowly, however, the law transformed the immigrant flow. Outmigration from northern and western Europe slowed to a trickle in the post-1965 years as the region recovered from the effects of World War II and enjoyed growth and prosperity. But in the developing world, gripped by turbulent decolonization movements, the pressures to migrate were increasing sharply. Improvements in global communication meant people everywhere were more aware of opportunities in distant lands, and the development of new transportation networks made movement easier and cheaper.

The family unification provision of the new immigration law meant that each migrant who somehow gained a foothold in the United States could soon invite family members to follow. A young African who came to America on a student visa or an engineer from South Asia with a US job offer could, within a few years, be responsible for the migration of dozens of relatives. A low-income migrant from Central America who previously might have been denied US entry based on a finding that he or she was “likely to become a public charge” now had an alternative way to qualify for admission: a family member willing to act as a sponsor.

Within a few years, it was apparent that the 1965 Immigration Act had made possible the very demographic transformation of the country that cultural conservatives had feared. No law passed in the twentieth century had a comparable effect. At the time of its passage, barely four percent of the US population was foreign born. Fifty years later, the immigrant share of the US population was near a historic high, and the foreign-born were coming from regions of the world that had never before produced many US immigrants. In 1960, seven of eight immigrants were from Europe. Today, nine of ten immigrants are coming from outside Europe, with Asia the leading source. The US Census Bureau projects that by 2045, the majority of the US population will be nonwhite.

Rural towns in the Midwest that were once entirely white now have a diversified population, with Somalis, Salvadorans, and Hmong joining the workforce and integrating the schools. Islam is the fastest growing religion in the country, and women in hijab are a common sight.  The rapidly evolving national identity is an alarming development to some, but in contrast to other countries where mass immigration has produced serious social and ethnic conflict, the integration of new cultures in America has been largely successful.

The rapidly evolving national identity is an alarming development to some, but in contrast to other countries where mass immigration has produced serious social and ethnic conflict, the integration of new cultures in America has been largely successful.

George Washington once declared, “The bosom of America is open to receive not only the Opulent and respectable Stranger, but the oppressed and persecuted of all Nations and Religions.”[9] That promise went unmet for nearly two centuries, perhaps out of a concern that such openness would be dangerous, but in 1965 the country took a big step to meet that founding ideal.

[1] Benjamin Franklin, “Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, etc.” (1751), printed in The Writings of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 3, ed. Albert Henry Smyth (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1907), 73.

[2] Prescott F. Hall, “Immigration and the Educational Test,” North American Review 165 (October 1897): 395.

[3] Whom We Shall Welcome: Report of the President’s Commission on Immigration and Naturalization (Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 1953), xiii.

[4] Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 89th Congress, First Session, vol. 111 (Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1965), 21773.

[5] Sam Ervin, comments before the Subcommittee on Immigration and Naturalization, February 24, 1965, in Immigration: Hearings before the Subcommittee on Immigration and Naturalization of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate, Eighty-Ninth Congress, First Session on S. 500 to Amend the Immigration and Nationality Act, Part 1 (Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 1965), 63.

[6] Deane and David Heller, “Our New Immigration Law,” American Legion Magazine (February 1966), 8.

[7] Congressional Record, vol. 111 (1965), 24503, quoted in David M. Reimers, Still the Golden Door: The Third World Comes to America (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992), 73.

[8] Lyndon B. Johnson, Remarks at the signing of the Immigration Bill, Liberty Island, New York, October 3, 1965, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/241316.

[9] George Washington, Address “To the Members of the Volunteer Association and Other Inhabitants of the Kingdom of Ireland Who Have Lately Arrived in the City of New York,” December 2, 1783, printed in The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745−1799, vol. 27, ed. John C. Fitzpatrick (Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 1938), 254.

Tom Gjelten is a correspondent for NPR News. He is the author of A Nation of Nations: A Great American Immigration Story (Simon & Schuster, 2015).