From The Editor

Every teacher knows that a novel can sometimes convey the mood and spirit of a historical era or event more powerfully than a textbook. And every teacher also knows that some novels have even made history. These are books that every student ought to read. In this issue, History Now focuses on six "books that changed history," placing each one in its historical context and suggesting why it remains relevant today. You are likely to be familiar with most of these books—perhaps one of them is your favorite novel. We hope you will enjoy what our scholars have to say about the authors, the characters, and the historical moment that these books capture on every page.

In "The Scarlet Letter and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s America," Brenda Wineapple examines the enduring popularity of a book that is in many ways alien in its pacing and its language to modern sensibilities. Yet students quickly get caught up in this tale of love and secrets and an extraordinary woman’s honor as Hawthorne makes a distant past come alive.

In "Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Matter of Influence," Hollis Robbins helps us understand why a book that is not a literary masterpiece can nevertheless have enduring importance in our national consciousness. While Harriet Beecher Stowe’s account of slavery may not have started a civil war, it certainly brought into sharp relief the sectional differences between North and South. We can learn much about attitudes of the day by examining the reasons why some ‘cussed’ and some praised this tale of cruelty, devotion, and the enduring human desire for freedom.

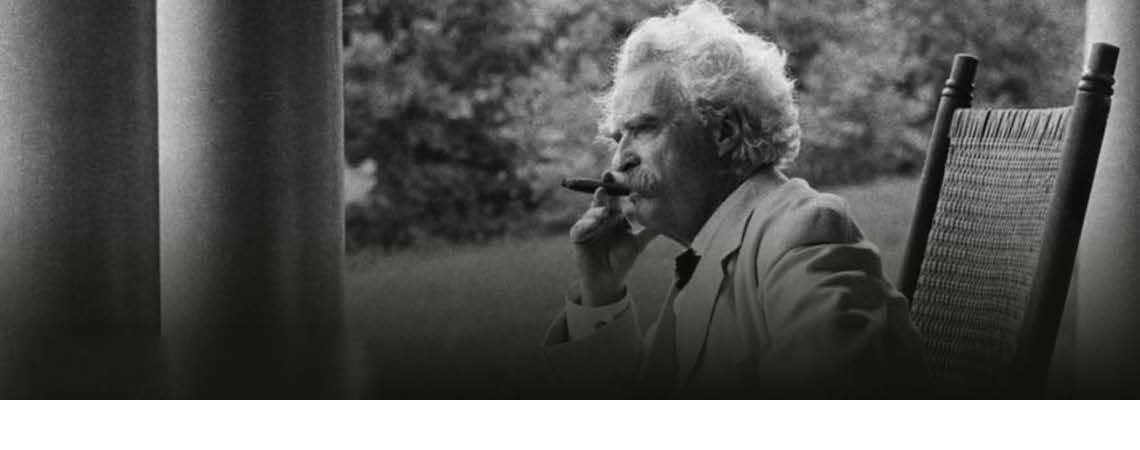

In "Rethinking Huck" Steven Mintz suggests why generations of young people—and older ones as well—love to travel the Mississippi with Huckleberry Finn. Not only does Mark Twain create a brilliant portrait of American society in the pre Civil War era, he gives us a pair of unlikely heroes whose adventures are, as Mintz notes, the first in a long line of "buddy stories." If the book is laced with humor it is also a serious critique of racism and it reminds us how difficult the path to self-discovery can be.

Perhaps the most famous expose of corruption and abuse of the public’s trust is Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. In "The Jungle and the Progressive Era" Robert Cherny takes a close look at the muckraking journalism of the Progressive era and at the conditions in factories, government, and cities that prompted reformers like Sinclair to expose the many pressing social problems to the public. Cherny points out how difficult it was for Sinclair to find a publisher for his story of an immigrant family whose hopes and dreams are dashed by the realities of industrializing America.

In "F.Scott Fitzgerald and the Age of Excess" Joshua Zeitz analyzes the book that best captured the highs—and lows—of the ‘roaring twenties.’ In The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald central character embodies both the ambition, the excesses, and the superficiality of the era; in his essay, Zeitz explains the rapid growth and underlying weaknesses of the era as well as its abrupt end in the Great Depression.

Finally, Timothy Aubry examines a book that every teenager has probably read and identified with: J.D. Salinger’s story of Holden Caulfield’s odyssey in search of an authentic self. In "The Catcher in the Rye: The Voice of Alienation," Aubry explains the lasting appeal of this classic tale of a sensitive misfit who refuses to grow up in a world whose values he rejects. Aubry carefully places Holden Caulfield’s private rebellion in the context of America in the 1950s, an age of optimism and anxiety, and an era of contradictions.

We hope this issue will prompt you to pack one or two—or all—of these great books in your suitcase wherever you are headed for your summer vacation!

Carol Berkin

Editor, History Now