The Scarlet Letter and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s America

by Brenda Wineapple

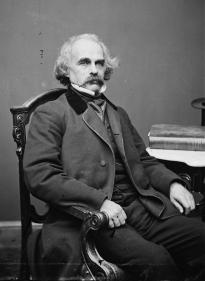

Nathaniel Hawthorne is the strange American author who has never been out of fashion; since his death in 1864, his stories and novels have resisted the tides of taste, canon reformation, and critical vicissitude. Herman Melville had to be "rediscovered" in the 1920s, Henry James fell out with the social realists of the 1930s (ditto Edith Wharton), and today formerly acclaimed novelists like William Dean Howells seem quaint or antiquated when placed alongside Thomas Pynchon, Don DeLillo, and Toni Morrison. Not Hawthorne. Henry James, William Faulkner, Robert Lowell, Flannery O’Connor, John Updike, Philip Roth—even Morrison herself—have had to come to terms with his work, as if Hawthorne were their literary father, which in a way he was, and even today writers as different from one another as Baharti Mukherjee, Paul Auster, Susan Lori Parks, Rick Moody, and Stephen King continue to refashion his tales and novels. And this cursory list does not even begin to include a multitude of Hawthorne-inspired plays, films, and operas.

Nathaniel Hawthorne is the strange American author who has never been out of fashion; since his death in 1864, his stories and novels have resisted the tides of taste, canon reformation, and critical vicissitude. Herman Melville had to be "rediscovered" in the 1920s, Henry James fell out with the social realists of the 1930s (ditto Edith Wharton), and today formerly acclaimed novelists like William Dean Howells seem quaint or antiquated when placed alongside Thomas Pynchon, Don DeLillo, and Toni Morrison. Not Hawthorne. Henry James, William Faulkner, Robert Lowell, Flannery O’Connor, John Updike, Philip Roth—even Morrison herself—have had to come to terms with his work, as if Hawthorne were their literary father, which in a way he was, and even today writers as different from one another as Baharti Mukherjee, Paul Auster, Susan Lori Parks, Rick Moody, and Stephen King continue to refashion his tales and novels. And this cursory list does not even begin to include a multitude of Hawthorne-inspired plays, films, and operas.

Take The Scarlet Letter. Just four years ago, an inventive New York City high school teacher asked me if I would come to her English class and talk about the novel with her students, almost all of whom spoke English as a second language. Consenting, I entered the plain cement-block public school by passing through a metal detector and found myself among a polyglot group of teenagers who, one after another, opened their dog-eared copies of The Scarlet Letter to read me passages aloud and then explain why Hester didn’t rat out Roger Chillingworth (partly she feared him, partly she resented Dimmesdale), why Reverend Dimmesdale seemed so weak (he was an egotist), why the Puritans dreaded the forest (it represented the scary unknown). Then they asked whether Hester’s illegitimate daughter, Pearl, was nuts. And they had other questions, too, just the sort of urgent ones that have beset readers for over 150 years: Why does Hawthorne admire and condemn Hester, a single mother, at the same time? What does Hawthorne tell us about the nature of friendship in the relationship between Chillingworth and Dimmesdale? Can men ever be friends? And what does the end of the novel mean: Why does Hester return to Boston, and can she really find peace with a new circle of female acquaintances, to whom she gives advice?

But, as these students admitted, initially the novel’s style had perplexed them. Hawthorne writes in an Augustan idiom, with long and sinuously balanced sentences peppered with commas. He sets his scene slowly. In Chapter One of The Scarlet Letter, we see a throng of men and women stand before a "wooden edifice, the door of which was heavily timbered with oak, and studded with iron spikes." But before we know more of these people or the occasion drawing them to this gloomy place, we learn that "the founders of a new colony, whatever Utopia of human virtue and happiness they might originally project, have invariably recognized it among their earliest practical necessities to allot a portion of the virgin soil as a cemetery, and another portion as a prison."

Why does such eloquence, alien as it may sometimes seem, withstand the dictates of time, place, age, or trend? Partly the answer lies in the fact that Hawthorne, as progenitor of the American canon, articulates a complex, ironic view of American history and culture. For instance, in The Scarlet Letter, he supplies a Romantic view of the Puritans as dour patriarchs wearing ruffs and lacking compassion that schoolchildren, reading the novel, assume to be accurate. (Many also assume Hawthorne lived in the seventeenth century, his depiction of colonial Boston seems so real.) Yet Hawthorne scrutinizes the foundation myths of America—its exceptionalism, its entrenched innocence, its sentimentality, its violence, and its cavalier attitude toward the past—with skeptical, often satiric eye. And in casting American history as perplexing moral drama in which the individual is beset by historical, cultural, and psychological limitations, he creates unforgettable characters and plangent symbols (the minister’s black veil, the scarlet letter, the Great Stone Face, the birth-mark) that provide Americans with a mirror through which we see our culture darkly and by which we have come to know ourselves and our nation if, as Hawthorne suggests, such knowledge is possible.

Human society: a utopia of virtue and happiness, or the site of sin and death, or both—these are the novel’s central ambiguities. Hawthorne is the master of ambiguity, which is another way of saying that he’s the master of duplicity, of saying one thing and meaning quite another. That technique lies at the heart of allegory, but Hawthorne was much more than an allegorist, for of all the standard nineteenth-century American authors, only Hawthorne created memorable women characters; Emerson did not. Thoreau did not. And certainly Melville placed no women aboard the fictional ships he sailed through the South Seas. Hawthorne is the great exception; he wrote about women’s rights, women’s work, women in relation to men, and social change. He wrote empathetically, sensitively, and also, sometimes, with disdain, converting his profound ambivalence about women, society, and politics into cultural symbols of ambiguity that, like the scarlet A, still baffle us, for what starts as a symbol drenched in infamy, signifying "adultery," becomes a badge of courage and integrity, worn by one who is able and angelic albeit tied forever to Arthur. The students in the New York City high school knew that.

They knew, too, that concealment is part of The Scarlet Letter, which is a book about, among other things, secrets. "We may prate of the circumstances that lie around us," Hawthorne writes in the introduction to The Scarlet Letter, "but still keep the Inmost Me behind the veil." Hester keeps not just the identity of her illegitimate daughter’s father a secret, but she keeps Chillingworth’s former relation to her, as her husband, a secret too; in fact, all the adult characters traffic in secrets, which makes some sense out of the narrator’s last injunction to the reader: "Be true! Be true! Show freely to the world, if not your worst, yet some trait whereby the worst may be inferred!"

But above all, Hawthorne’s supreme achievement is Hester Prynne herself, who stands when we first meet her, straight and tall, imperial and grand, proud and strong and isolated from the community. Part Anne Hutchinson (about whom Hawthorne wrote earlier) and part Ralph Waldo Emerson, Hester is further derived from a number of Hawthorne’s friends and relatives, prominent among them the feminist Margaret Fuller, whom Hawthorne knew well, especially in the years before he wrote The Scarlet Letter, and whose Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1845) urged women to fulfill whatever destiny they desired: "if you ask me what offices they may fill, I reply—any. . . . Let them be sea-captains, if you will." Also contributing to the portrait of Hester was Hawthorne’s mother, herself a single parent of sorts, Hawthorne’s father having died when he was just four; and doubtless in Hester there’s a touch of Hawthorne’s elder sister, an eccentric woman with a very tart tongue. "Useful knowledge," she liked to say to her brother, "is the most useless of all. . . . If you ever write a book, take care that it be with no intention to be useful." I think, too, that Hester contained Elizabeth Peabody, Hawthorne’s sister-in-law, a woman blessed with good intentions, who introduced the idea of kindergarten to America and believed in change of all kind, from educational reform to the abolition of slavery to the fair and just treatment of Native Americans.

For Hawthorne was very much a man of his time and not that of the Puritans about whom he so eloquently wrote. Which isn’t to say that he did not care for them; he did—with classic ambivalence. Puritans and colonial New Englanders are the subject of many of his stories. "The past is never dead," Hawthorne writes in "The Custom House" essay that precedes The Scarlet Letter. But Hawthorne also saw the railroad bring the ends of the country together, and the telegraph reconfigure space and time; he watched photography change the meaning of art and portraiture, which were the subjects of his next novel, The House of the Seven Gables; and he heard all the debates then raging for and against industrialization, abolition, wage-slavery, and capitalism. He even participated, for a short while, in a commune, before he married. He was good friends with Franklin Pierce, the fourteenth president of the United States. And he had to feed and support a growing family "in a republican country," as he put it, in which "somebody is always at the drowning point."

After the election of James Polk as United States president in 1844, Hawthorne’s political friends rallied round him and found him a civil service appointment as surveyor in the Salem Custom House, where he worked until the Whigs regained the presidency in 1848 and forced him out. In "The Custom House" essay, written to pillory the patronage system that deprived him of his post (even though it would in four years provide him with another one), he presents himself as the somewhat reluctant employee who one day stumbles on an artifact, a red cloth embroidered as the letter A, among the personal effects of a former surveyor in the dusty attic of his workplace. Curious, he happens to place the letter on his chest, but it’s so hot it burns him and he drops it to the floor. So Hawthorne, as is frequent with him, becomes one more character in his own tale, a nineteenth-century man who touches the seventeenth-century by means of an eighteenth-century surveyor (the past is never dead).

When Hawthorne’s publisher, James T. Fields, read the unfinished manuscript of The Scarlet Letter, he insisted it be published as a novel, not a short story; and from then on he marketed Hawthorne’s work with entrepreneurial genius. "Somehow or other," Hawthorne later thanked him, "you smote the rock of public sympathy on my behalf." Even more importantly, Fields supplied the encouragement that Hawthorne needed in order to write and to face the consequences of writing, including neglect and bad reviews.

For let’s not forget that by 1850, the year of The Scarlet Letter’s publication, Hawthorne had been writing for more than twenty years. In 1828, he had published, anonymously and at his own expense, his first book, Fanshawe, a huge failure; a proud man, Hawthorne later destroyed as many copies of this novel as he could find and, years hence, pretended it didn’t exist. But he continued to write short stories and sketches and in 1837 collected them into the volume Twice-Told Tales, a critical success that didn’t much sell. He was like a man talking to himself alone in a dark place, he told a friend, and once mocked himself as "the obscurest man of letters in America."

But The Scarlet Letter received much acclaim. Hailed as original, touching, deep in thought and condensed in style, it also sold 4,500 copies almost immediately. Readers responded viscerally to Hester Prynne, and they still do, as if her fate summons forth anew, generation after generation, that unexpected bedfellow of American history, and female strength and sexuality. No American character—no female protagonist before or since—has galvanized readers in quite the same way. As a result, The Scarlet Letter continues to enthrall, asking us over and over what it means to live with others and feel apart; to be part of history yet separate from it; to love passionately and never forget; to hope too long, plot secrets, face reality, feel scared, and yet still believe in the promise, as Hester does at the novel’s end, of a better world—and whose promise, perhaps illusory, she will share with other women. As Hawthorne will, even when he is most skeptical. "My theory is," Hawthorne told a friend, "that there is less indelicacy in speaking out your highest, deepest, tenderest emotions to the world at large, than to almost any individual. You may be mistaken in the individual; but you cannot be mistaken in thinking that, somewhere among your fellow-creatures, there is a heart that will receive yours into itself."

Brenda Wineapple is the Director of the Leon Levy Center for Biography at The Graduate School, City University of New York, and teaches in the MFA programs at The New School and Columbia University’s School of the Arts. She is the author of Hawthorne: A Life (2003) and White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson (2008).