Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Matter of Influence

by Hollis Robbins

One hundred years after Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852, the poet Langston Hughes called the novel, "the most cussed and discussed book of its time." Hughes’s observation is particularly apt in that it avoids any mention of the novel’s literary merit. George Orwell famously called it "the best bad book of the age." Uncle Tom’s Cabin is arguably no Pride and Prejudice or Scarlet Letter. Leo Tolstoy is one of the few critics who praise it unabashedly, calling Uncle Tom’s Cabin a model of the "highest type" of art because it flowed from love of God and man. So why has it been called "a verbal earthquake, an ink-and-paper tidal wave"? How and why has it been so influential?

One hundred years after Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852, the poet Langston Hughes called the novel, "the most cussed and discussed book of its time." Hughes’s observation is particularly apt in that it avoids any mention of the novel’s literary merit. George Orwell famously called it "the best bad book of the age." Uncle Tom’s Cabin is arguably no Pride and Prejudice or Scarlet Letter. Leo Tolstoy is one of the few critics who praise it unabashedly, calling Uncle Tom’s Cabin a model of the "highest type" of art because it flowed from love of God and man. So why has it been called "a verbal earthquake, an ink-and-paper tidal wave"? How and why has it been so influential?

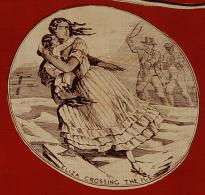

Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or Life among the Lowly is at heart a typical nineteenth-century melodrama of cruelty, suffering, religious devotion, broken homes, and improbable reunions. The plot in brief: the slave Uncle Tom is sold away from his cabin and family on the Shelby plantation in Kentucky; he serves the St. Clare family in Louisiana, from which he is sold after the death of Eva and her father; he lands at the Legree plantation on the Red River where he is whipped to death rather than betray two runaway slaves. Meanwhile some slaves escape (Eliza on ice floes across the Ohio River) and find long-lost relatives; others kill themselves and their children. The white characters discuss politics and religion. Everybody weeps.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin has been cussed and discussed since May 8, 1851, when the novel’s first installment appeared in abolitionist Gamaliel Bailey’s Washington, DC, weekly, the National Era. Cussers include Southerners such as William Gilmore Simms, who considered the novel a libelous hodgepodge of bad research and flat-out lies; Reverend Joel Parker, who threatened to sue Stowe for the "dastardly attack" on his character; Charles Dickens, who wondered if Stowe patterned Eva on his Little Nell; and James Baldwin, who bemoaned the sentimentality and the powerlessness of Uncle Tom. Discussers include everybody else: Frederick Douglass, Ralph Waldo Emerson, George Eliot, Horace Mann, Mark Twain, Charles Dudley Warner, Henry James, and in modern times, Richard Wright, Harold Bloom, Elaine Showalter, Ann Douglas, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and John Updike, who confessed to having never read the novel until he reviewed it in the New Yorker in 2006.

Nearly everyone agrees that the reason for Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s initial influence was a matter of timing. Its author, Harriet Beecher Stowe, was the perfect combination of magpie, shrewd political operator, and grieving mother. After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the time was right for an anti-slavery novel and Stowe wrote one (though she claimed later that God himself held the pen). But Stowe’s beliefs about slavery’s effects on family did not simply manifest themselves in a fictional story. The brutal facts of slavery did not automatically translate themselves into an effective political tract. The reading public may have been primed and ready for the right anti-slavery story to come along and simply "touch a nerve" or "strike a chord," but why was this novel the "right" story?

Sales and readership figures demonstrate Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s popular appeal. Readership of the National Era jumped from 17,000 to 28,000 during the story’s serialization. On March 20, 1852, John J. Jewett & Co. published the first one-volume edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and sold 5000 copies in two days. Over 100,000 copies were sold by the end of the summer and 300,000 by March 1853. One southern literary critic credited new technology for the novel’s sales figures, which relied on "steam-presses, steam-ships, steam-carriages, iron roads, electric telegraphs, and universal peace among the reading nations of the earth." Hundreds of editions and millions of copies have been sold around the world. Uncle Tom’s Cabin remains the world’s second most translated book, after the Bible.

The literary influence of Stowe’s novel is evidenced by the immortality of Uncle Tom, Eliza, Little Eva, Simon Legree, and Topsy. These characters exist beyond Stowe’s tale; they have become literary archetypes. Uncle Tom began as a Christ figure—a character like Jesus who loves God, loves his tormentors, turns the other cheek, and shows inhuman forbearance in the face of cruelty—but has been transformed into the perfect, silver-haired, silent, sexless, stalwart servant. Eliza remains, however, the model of the desperate mother who will leap across the ice to save her child. The name "Simon Legree" is shorthand for any cruel overseer. Topsy is the avatar of the mischief-maker, the magic urchin who asserts her own alien status, claiming, "I spect I grow’d. Don’t think nobody never made me." These characters appeared in popular poems, cartoons, and songs within weeks. Dramatic versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin appeared within months; George L. Aiken’s stage production remained the most popular play in England and America for seventy-five years. Henry James compared the many spin-offs Stowe’s novel provoked to "a wonderful leaping fish" that "fluttered down" around the globe. Modern theatergoers may know "The Small Cabin of Uncle Thomas," the version that appears in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical The King and I.

The political influence of Uncle Tom’s Cabin can be measured by who talked about it or who used it as a rationale for action. Exhibit A is the remark supposedly made by President Lincoln when he met Stowe in 1862: "So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that started this Great War." True or not, its circulation is testament to both Lincoln’s and Stowe’s sense of public relations. Exhibit B is everyone else who saw Uncle Tom’s Cabin as revolutionary. Frederick Douglass wrote of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that "nothing could have better suited the moral and humane requirements of the hour. Its effect was amazing, instantaneous, and universal." It was banned in the South and nearly banned by the Vatican. It was also banned in tsarist Russia, but apparently Uncle Tom’s Cabin was Lenin’s favorite book as a youth. Woodrow Wilson wrote that Uncle Tom’s Cabin "played no small part in creating the anti-slavery party." Yet in the twentieth century, Malcolm X suggested that it wasn’t radical enough, claiming that Martin Luther King Jr. was a "modern" Uncle Tom, "who is doing the same thing today, to keep Negroes defenseless in the face of an attack."

Rather than "a book that made history," Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a novel that matters because it is still provokes argument. Many modern readers wish Uncle Tom would stop praying and serving and do something. W. E. B. Du Bois saw Tom’s "deep religious fatalism" as an example of the stunted ethical growth endemic to plantation existence, where "habits of shiftlessness took root, and sullen hopelessness replaced hopeful strife." In Nabokov’s Lolita, the porter who carries the bags to the hotel room where Humbert Humbert will first have his way with his young stepdaughter is called "Uncle Tom." He will not get involved. Unfounded as the term and the application may be, "Uncle Tom" remains, even today, the standard epithet for any black man who serves whites and does not carry a gun. Indeed, in recent history, the term has been applied to Dr. King, Clarence Thomas, Colin Powell, and Barack Obama.

Much of the cussing and discussing of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin comes from those who haven’t actually read the book. Those who have know that the power of Stowe’s novel resides in the dozens of her characters who enter our consciousness by acting fully human: Senator Bird, who reluctantly agrees that the letter of the Fugitive Slave Law does not trump his Christian duty to break the law and help the runaway Eliza and her son; Marie St. Clare, vain and whiny, who sees her daughter Eva’s death as a personal affront; Ophelia, the prim Vermonter who finds slavery and blacks equally abhorrent; Augustine St. Clare and Arthur Shelby, thoughtful and good-hearted but utterly weak; and Sam, whose "comic inefficiency," critic Kenneth Lynn writes, "no American author before Mrs. Stowe had realized . . . could constitute a studied insult to the white man’s intelligence." To read and take seriously the entirety of Uncle Tom’s Cabin is to see why it matters not as a historical or political phenomenon but as a relentless and passionate work of literary fiction.

Hollis Robbins is the co-editor with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., of The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin (2006) and The Selected Writings of William Wells Brown (2006) with Paula Garret. She is a member of the Humanities Faculty at The Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University.

Suggested Sources

Books and Printed Materials

On Uncle Tom’s Cabin:

Ammons, Elizabeth, ed. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin: A Casebook. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Morgan, Jo-Ann. Uncle Tom's Cabin as Visual Culture. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2007.

Stowe, Harriet Beecher. The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Hollis Robbins. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2007. [Particularly check the suggested readings in this edition.]

On the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850:

Campbell, Stanley W. The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850–1860. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970.

On Harriet Beecher Stowe:

Boydston, Jeanne. The Limits of Sisterhood: The Beecher Sisters on Women’s Rights and Woman’s Sphere. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988.

White, Barbara Anne. The Beecher Sisters. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Wilson, Robert Forrest. Crusader in Crinoline: The Life of Harriet Beecher Stowe. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1941.

On using Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the classroom:

Ammons, Elizabeth, and Susan Belasco, eds. Approaches to Teaching Stowe’s Uncle Tom's Cabin. New York: Modern Language Association of America, 2000.

Internet Resources

Stephen Railton’s "Uncle Tom’s Cabin and American Culture" on the University of Virginia website, including lesson plans and the interpretive exhibitions section:

http://www.iath.virginia.edu/utc/index2f.html

http://jefferson.village.virginia.edu/utc/interpret/lessons/lessonshpf.html

http://jefferson.village.virginia.edu/utc/interpret/interframe.html

The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford, Connecticut, includes teacher resources:

http://www.harrietbeecherstowecenter.org/

http://www.harrietbeecherstowecenter.org/hbs/

http://www.harrietbeecherstowecenter.org/worxcms_published/school_page110.shtml

http://www.harrietbeecherstowecenter.org/worxcms_published/school_page108.shtml