Immigration Policy, Mexican Americans, and Undocumented Immigrants, 1954 to the Present

by Eladio Bobadilla

In 1953, a pamphlet ominously tilted What Price Wetbacks? circulated widely throughout the American Southwest. Its authors warned that a “wetback invasion” was underway, one that posed “a threat to our health, our economy, [and] our American way of life.”[1] A contemporary observer might be forgiven for assuming such was the work of a xenophobic outlet or a nativist group. In reality, the now-infamous pamphlet was the work of a respected Mexican American advocacy organization, the American GI Forum, with the backing of the Texas Federation of Labor.

Two decades later, the American GI Forum once again emerged as a central voice in the immigration debate. But this time, rather than warning about “wetbacks”—a term of derision recognized even in the 1950s as a racial slur—the GI Forum now proclaimed its unconditional support for the undocumented, proudly proclaiming that it stood “alongside all gente” without documents, and telling its members that “we cannot stop [organizing] until full amnesty is realized.”[2] The GI Forum was not alone in this profound transformation. Other organizations that altered or completely reversed their positions on immigration by the late 1970s included the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), the National Council of La Raza (NCLR), the Mexican American Political Association (MAPA), and perhaps most strikingly, the United Farm Workers union (UFW). In short, by 1980, every major Mexican American organization had come to embrace the cause of the undocumented.[3]

How did this remarkable transformation happen? A number of interrelated factors and developments came together to encourage the formation of a pro-immigrant consciousness among Mexican Americans so significant that contemporary observers regularly treat it as a natural, fixed, and ahistorical position. But the formation of this “without borders” ideology was anything but a given. While Mexican Americans had always understood the culture that tied them to their co-ethnics south of the border, previous experience suggested this was not enough to form a natural alliance. What Price Wetbacks? and the larger context in which it emerged were testament to that. When in the late 1950s the United States found itself in the midst of a ferocious recession, Mexican immigrants proved easy scapegoats. Leading Mexican Americans, along with anxious Anglos, heartily supported the mass deportation of Mexican workers in what became known as Operation Wetback.

Operation Wetback did not solve the problem of unsanctioned migration, however. In fact, it was never intended to. Operation Wetback, above all, was political sleight of hand meant to appease nativists while continuing to ensure farmers, growers, and other employers of cheap Mexican labor continued to have access to workers. Many of those “deported” were merely paroled to farmers.[4] Others were sent across the border and turned into braceros, temporary workers who had been brought to the United States since the outbreak of World War II to work on farms, railroads, and other industries suffering worker shortages as result of the war effort. Many more simply returned.

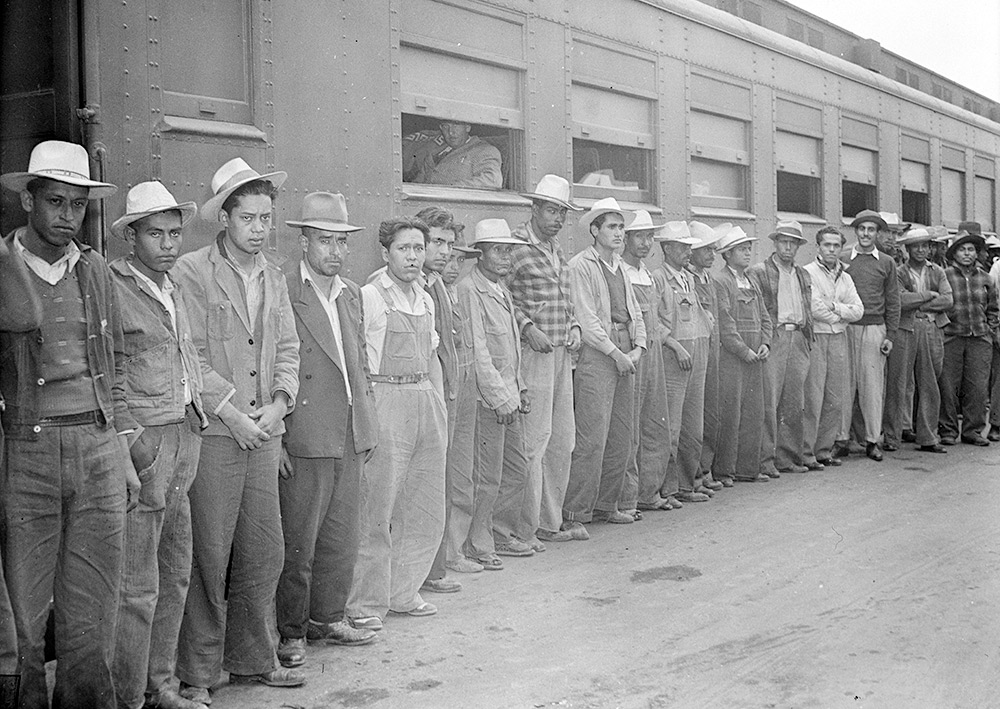

In 1942, the United States responded to worker shortages resulting from the deployment of millions of young men to fight in World War II by launching the Bracero Program, a series of bilateral agreements with Mexico to import Mexican men to work in the States. Mexico, for its part, hoped the experience would give its economy a lift, both by encouraging workers to spend money they made in the US when they returned home and by providing them with experience they could apply to the country’s quickly industrializing sectors.[5]

In 1942, the United States responded to worker shortages resulting from the deployment of millions of young men to fight in World War II by launching the Bracero Program, a series of bilateral agreements with Mexico to import Mexican men to work in the States. Mexico, for its part, hoped the experience would give its economy a lift, both by encouraging workers to spend money they made in the US when they returned home and by providing them with experience they could apply to the country’s quickly industrializing sectors.[5]

The Bracero Program, which imported some five million men during the course of its existence from 1942 to 1964, was considered a major problem by leading Mexican Americans, who believed the system at once exploited Mexican workers—who worked long hours, under horrific conditions, for as little as $20 a week—and hurt American-born workers by creating unnecessary competition, depressing wages, and thwarting labor organizations.[6] Worse, it encouraged “illegal immigration.” For this reason, even as Mexican Americans combatted the “invasion” of unsanctioned workers, they also fought to end the Bracero Program, which had not ended with World War II but instead was modified and extended at the beginning of a new conflict, the Korean War. The 1951 revisions, known as Public Law 78, streamlined the process by which the secretary of labor certified the need for workers, making it easier for employers to import large numbers of Mexican workers. The number of braceros increased markedly after 1951, reaching a high of almost half a million each year between 1956 and 1959.[7] This surge in bracero use prompted a strong, organized backlash from Mexican Americans and labor unions, with figures like Ernesto Galarza and Cesar Chavez leading the fight.

By the beginning of the 1960s, Mexican Americans, labor unions, and others had gained momentum in their efforts to end the program, which was finally terminated in 1964. This was not the only crucial development in immigration history around this time, however.  The following year, Congress passed and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act. Ostensibly a progressive piece of legislation, it eliminated national origins quotas, first introduced in 1924 and reaffirmed in 1952. The act, often referred to as Hart-Celler, after its principal sponsors, sought to bring immigration policy in line with civil rights legislation. Specifically, it sought to make the immigration process more fair. To that end, instead of national origins quotas, numerical limits were instituted by hemisphere.

The following year, Congress passed and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act. Ostensibly a progressive piece of legislation, it eliminated national origins quotas, first introduced in 1924 and reaffirmed in 1952. The act, often referred to as Hart-Celler, after its principal sponsors, sought to bring immigration policy in line with civil rights legislation. Specifically, it sought to make the immigration process more fair. To that end, instead of national origins quotas, numerical limits were instituted by hemisphere.

The problem, of course, was that not all countries were equal in their need for legal visas nor in their likelihood to send large numbers of their citizens to the United States. By placing all Western hemisphere countries under one numerical limit at precisely the same time the Bracero Program ended, the law inadvertently created the modern problem of “illegal immigration,” as poor Mexicans, rocked by continued political instability, out-of-control inflation, rampant corruption, and a population boom decades in the making, continued to migrate north without documents.[8] Between 1969 and 1975, the population of undocumented immigrants in the United States rose from half a million to over a million and doubled again by 1980 to some three million.

As Mexicans poured across the border after 1965, however, Mexican Americans generally welcomed and supported them, though there were exceptions. The iconic labor leader Cesar Chavez and his United Farm Workers union, for example, continued to believe that undocumented immigrants posed a threat to the advancement of poor Mexican Americans—and worked hard to keep them out of the country and away from the fields. But soon, Chavez realized he was virtually alone in this position.[9]

There were a number of reasons for this. One was that even as Chavez sought to keep immigrants from crossing the border, others had realized this was not going to happen and were having success organizing them. Another was that civil rights legislation had changed the political and social calculus for Mexican Americans. Whereas an earlier generation of Mexican Americans could only hope to advance by claiming to be white, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had given them the opportunity to seek protections as minorities.[10] Additionally, as the population of immigrants grew, so did a nativist backlash whose rhetoric lumped together American-born ethnic Mexicans, legal permanent residents, and undocumented immigrants. With increased contact and an increase in shared threats, bonds among Mexican Americans formed and cemented.

There were a number of reasons for this. One was that even as Chavez sought to keep immigrants from crossing the border, others had realized this was not going to happen and were having success organizing them. Another was that civil rights legislation had changed the political and social calculus for Mexican Americans. Whereas an earlier generation of Mexican Americans could only hope to advance by claiming to be white, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had given them the opportunity to seek protections as minorities.[10] Additionally, as the population of immigrants grew, so did a nativist backlash whose rhetoric lumped together American-born ethnic Mexicans, legal permanent residents, and undocumented immigrants. With increased contact and an increase in shared threats, bonds among Mexican Americans formed and cemented.

Still, there were challenges to come. In 1973, immigration reform legislation was introduced meant to punish employers who used undocumented labor, to strengthen the border, and to provide amnesty to some undocumented immigrants already in the country. Immigration reform became a hot topic by the late 1970s, as the hysteria about immigrants began to mount. Despite the failure of earlier efforts, President Jimmy Carter managed to create a select commission on immigration, headed by the respected scholar and Catholic priest Theodore Hesburgh. The commission studied the matter for three years and issued a wide-ranging report, whose recommendations were taken up by a new administration.[11]

After several years of debate, Congress passed and Ronald Reagan signed into law the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986, which sought a three-pronged approach to immigration: border enforcement, employer sanctions, and amnesty. Mexican Americans were conflicted. On the one hand, they regarded the first two measures as discriminatory. On the other hand, they acknowledged that amnesty changed the lives of millions of people for the better.

After several years of debate, Congress passed and Ronald Reagan signed into law the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986, which sought a three-pronged approach to immigration: border enforcement, employer sanctions, and amnesty. Mexican Americans were conflicted. On the one hand, they regarded the first two measures as discriminatory. On the other hand, they acknowledged that amnesty changed the lives of millions of people for the better.

By the mid-1980s, most Mexican Americans sought to support and protect undocumented immigrants. And while the legalization effort had changed the lives of millions of people (mostly men), there was an almost immediate backlash to IRCA. California, host to the largest number of undocumented immigrants in the 1980s and 1990s, quickly became proving grounds for new nativist legislation. In 1994, California overwhelmingly passed Proposition 187, a restrictionist and draconian piece of legislation designed to deny public services to undocumented immigrants and their children. Though quickly found unconstitutional, the law served as a model for other restrictive laws across the country over the next couple of decades. Proposition 187 also signaled a “new nativism” that saw in Latinos, not just immigrants, a “threat” to American culture and society.[12] Recognizing this, Mexican Americans have understood anti-immigrant rhetoric in much the same way that activist Herman Baca did when he proclaimed in 1986 that “the hysteria against them” (undocumented immigrants) “impacts us” (Hispanics more broadly).[13]

The “187 Effect,” as one political scientist has termed it,[14] has not been enough to dispel anti-immigrant fears and myths or to dissuade politicians from engaging in xenophobic dog-whistle politics. In fact, the rise of Donald Trump and the alt-right has been the result, at least in part, of a strong and recurring nativist faction. At the same time, immigrants no longer find themselves alone, and Hispanics, for whom immigration remains a central and defining issue, have grown to constitute a valuable and often decisive social and voting bloc, one that has, in recent years, taken up the task of igniting what Rep. John Lewis has called a new civil rights movement.[15]

The “187 Effect,” as one political scientist has termed it,[14] has not been enough to dispel anti-immigrant fears and myths or to dissuade politicians from engaging in xenophobic dog-whistle politics. In fact, the rise of Donald Trump and the alt-right has been the result, at least in part, of a strong and recurring nativist faction. At the same time, immigrants no longer find themselves alone, and Hispanics, for whom immigration remains a central and defining issue, have grown to constitute a valuable and often decisive social and voting bloc, one that has, in recent years, taken up the task of igniting what Rep. John Lewis has called a new civil rights movement.[15]

Eladio Bobadilla is a PhD candidate in history at Duke University, where he is currently finishing his dissertation on the history of the modern immigrants’ rights movement. Previously, he attended Weber State University and served in the United States Navy. He is the recipient of a 2018 Gilder Lehrman Scholarly Fellowship and an immigration policy expert for the Scholars Strategy Network.

[1] What Price Wetbacks? (Austin: The American GI Forum of Texas and the Texas State Federation of Labor [AFL], 1953), 1.

[2] Telegram from Gilbert Rodriguez to Herman Baca, February 12, 1979. Herman Baca Papers, MSS 0649, Box 18, Folder 11, Mandeville Special Collections Library, University of California, San Diego.

[3] For the most thorough and still one of the only comprehensive historical studies of the subject, see David Gutiérrez, Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the Politics of Ethnicity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

[4] See Kelly L. Hernández, “The Crimes and Consequences of Illegal Immigration: A Cross-Border Examination of Operation Wetback,” Western Historical Quarterly 37, no. 4 (2006): 421–444, and Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004).

[5] See Deborah Cohen, Braceros: Migrant Citizens and Transnational Subjects in the Postwar United States and Mexico (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

[6]Don Mitchell, They Saved the Crops: Labor, Landscape, and the Struggle over Industrial Farming in Bracero-Era California (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012), 249.

[7] Robert C. McElroy and Earle E. Gavett, Termination of the Bracero Program: Some Effects on Farm Labor and Migrant Housing Needs, Agricultural Economic Report No. 77 (Washington DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, June 17, 1965).

[8] Ngai, Impossible Subjects, 257.

[9] Frank Bardacke, “The UFW and the Undocumented,” International Labor and Working Class History 83 (2013): 162–169.

[10] Nancy MacLean, “The Civil Rights Act and the Transformation of Mexican American Identity and Politics,” Berkeley La Raza Law Journal 18 (2007): 123–133.

[11] [Theodore Hesburgh], US Immigration Policy and the National Interest: The Final Report and Recommendations of the Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy with Supplemental Views by Commissioners, March 1, 1981 (Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 1981).

[12] Robin Dale Jacobson, The New Nativism: Proposition 187 and the Debate over Immigration (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008).

[13] “La Frontera: America’s Dilemma,” La Prensa, June 20, 1986. Herman Baca Papers, MSS 0649, Box 1, Folder 9, Mandeville Special Collections Library, UCSD.

[14] Matt Barreto, “The Prop 187 Effect: How the California GOP Lost Their Way and Implications for 2014 and Beyond,” Latino Decisions (blog), posted October 17, 2013, http://www.latinodecisions.com/blog/2013/10/17/prop187effect/.

[15] “10 Questions: John Lewis,” Time, April 10, 2017, http://time.com/4718026/john-lewis-10-questions/.