The League of the Iroquois

by Matthew Dennis

No Native people affected the course of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century American history more than the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois, of present-day upstate New York. Historians have been attempting to explain how and why ever since, and central to their explanations is the remarkable political and diplomatic structure, the League of the Iroquois. The League has fascinated us for hundreds of years. In the seventeenth century, this Native confederacy united the Five Iroquois Nations—the Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Senecas—into something more than an alliance but something less than a single, monolithic polity. In the eighteenth century, the incorporation of the Tuscaroras made it the Six Nations of the Iroquois.

No Native people affected the course of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century American history more than the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois, of present-day upstate New York. Historians have been attempting to explain how and why ever since, and central to their explanations is the remarkable political and diplomatic structure, the League of the Iroquois. The League has fascinated us for hundreds of years. In the seventeenth century, this Native confederacy united the Five Iroquois Nations—the Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Senecas—into something more than an alliance but something less than a single, monolithic polity. In the eighteenth century, the incorporation of the Tuscaroras made it the Six Nations of the Iroquois.

The Iroquois demanded attention. Their strategic geographic position, diplomatic savvy, military might, and astonishing resilience captivated white officials, settlers, and observers throughout the colonial period and beyond. To advance their goals, colonial authorities were forced to work with, against, or through the Iroquois League. Yet such engagement was often built not on genuine understanding of the Iroquois worldview, society, and politics, but on ethnocentric projections of white visions and desires. Into the present, such fantasies continue to enthrall us, and prevent us from understanding the Haudenosaunee and their history.

In the eighteenth century, English colonial authorities artfully imagined that the Iroquois held dominion over an exaggerated range of lands and peoples, and, by claiming the Iroquois as their client, they extended their own authority over those territories and Native communities, at least conceptually. Iroquois power was real, but an Iroquois European-style "empire" was not.

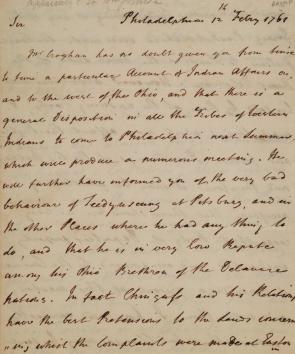

Following the American Revolution, which divided the Six Nations, depleted their numbers, and devastated their homeland, the Haudenosaunee revived and remained diplomatically significant. When a delegation visited the United States capital in Philadelphia in 1792, it was received lavishly, its chiefs referred to as "Princes." Philip Freneau, editor of the National Gazette, objected and, in keeping with the times, relabeled them "republicans rather than aristocrats or monarchy men."[1] New York statesman DeWitt Clinton soon transformed them into avatars of imperial, rather than republican, Rome. Addressing the New-York Historical Society in 1811, Clinton famously called the historic Iroquois "the Romans of this western world."[2] The father of American ethnology, Lewis H. Morgan, similarly deployed the metaphor in his classic work, League of the Ho-de-no-sau-nee, or Iroquois (1851), inventing a Pax Iroquoia to resemble the Pax Romana of the ancient world.

Such ascribed imperial status became thoroughly conventional in the nineteenth century. As Iroquois power substantially diminished, white Americans often imagined (inaccurately) that the Iroquois had vanished altogether, and in romantic poems and prose they engaged in nostalgic flights of fancy. A self-described "dabbler in literature and art," for example, narrated a tour through lands that were once Iroquoia for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1856. "Historically and legendarily, it is a classic region," he wrote, boasting that he had "the rare good luck of spending an afternoon with the fine poet, Hosmer, whose genius has embalmed in the fragrant amber of verse many of the most beautiful romances of the Six Nations—the Romans of the Western World."[3] The prelude to William H. C. Hosmer’s 1844 poem Yonnondio captures this imperial nostalgia:

Realm of the Senecas! no more

In shadow lies the Pleasant Vale;

Gone are the Chiefs who ruled of yore,

Like chaff before the rushing gale.

Their rivers run with narrowed bounds,

Cleared are their broad, old hunting grounds,

And on their ancient battle fields

The greensward to the ploughman yields;

Like mocking echoes of the hill

Their fame resounded and grew still,

And on green ridge and level plain

Their hearths will never smoke again.[4]

Citizens of the new republic created a novel, yet classical identity for themselves in places like New York, borrowing names from antiquity for their towns and cities—Ithaca, Rome, and Syracuse, for example—and enlisting the supposedly extinct Iroquois as indigenous antique ancestors while celebrating their League as the Iroquois’ "Federal Republic." And if somehow Iroquois could be dead Romans, then inanimate Romans could be Iroquois. According to his biographer, writing in 1820, the expatriate American history painter Benjamin West, upon viewing the marble Apollo Belvedere in Rome’s Vatican museum, exclaimed, "My God, how like it is to a young Mohawk warrior!"[5] Thus, in the American imagination, the Iroquois became relics, not complex living people.

What are the concrete historical realities obscured by this apocrypha?

Archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests that the Iroquois began to consolidate as a people in what is now central New York State about a thousand years ago. Their ethnic and cultural composition predates the formation of their famous League of Peace, and scholars are divided about the timing of its origin. Some date it to the fifteenth century, some earlier, and some argue that it was a late adaptive response to European colonialism in the early seventeenth century. But it seems clear that the spirit and purpose of the League is ancient, even if its precise framework, protocols, and offices are not.

In Iroquoia—the Five Nations’ homeland between the Mohawk and Genesee Rivers in central New York—the Haudenosaunee sought to construct a cultural landscape of peace, security, and prosperity. Intermarriage, interlocking kinship ties, and an elaborate clan organization wove together the various tribes and communities and undergirded political alliance and cooperation. Archaeologists have discerned these patterns in the ways that the first millennium ancestors of the historic Iroquois consolidated their villages over time, moved closer to one another, domesticated more space, and increased the dimensions of their longhouses.

For the Iroquois, these longhouses—traditional multifamily dwellings—symbolized and embodied their expanding world of peace, as the structures’ end-walls could be removed and more hearths added to accommodate new families who joined the Haudenosaunee through marriage, adoption, or amalgamation. As Horatio Hale, the late-nineteenth-century ethnologist and student of the Iroquois, explained, "Such was the figure by which the founders of the confederacy represented their political structure, a figure which was in itself a description and an invitation. It declared that the united nations were not distinct tribes, associated by a temporary league, but one great family, clustered for convenience about separate hearths in a common dwelling."[6] Peace and security would expand as potentially hostile space was transformed into a place of domesticity. Hale likely overstated the extent of political integration. The Iroquois continued to value localism, and their communities retained considerable autonomy, but throughout the colonial period the People of the Longhouse, bound together by their League, often acted in coordinated fashion as they pursued common social, political, and economic objectives.

The Iroquois ideal of peace appears most clearly in the great chartering myth embodied in their epic of the Peacemaker. In some remote time, the Iroquois believe, their world was roiled by incessant violence and dangerous chaos. A great prophet emerged who ended the internecine bloodshed, unified the people, and provided a new moral order and charter of peace known as the Great Law. Through laws, rites, and everyday practices, the Iroquois institutionalized peace. The Peacemaker’s diplomacy ultimately won the support of each of the Five Nations, with his greatest triumph being the pacification of a powerful and maleficent Onondaga chief, Thadodaho. Subsequently, Thadodaho become the new League’s leading sachem—the "first among equals" that included some fifty confederacy chiefs—and Onondaga became the place of the central council fire. The successor "federal chiefs" embody the founders in name and position and are arrayed not merely by tribe but also on the basis of clans, which cut across Iroquois nations. This complicated social and political structure lent greater strength and unity to the League. Some scholars argue that unity and peace at home enabled Iroquois aggression abroad; others see the warfare that enveloped the Iroquois in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as a more defensive response to the complicated geopolitics of a North America roiled by colonialism.

The protocols of the League mirrored and modeled practices in everyday Iroquois social and political life. When one of its members died, for example, the fifty League chiefs divided themselves into two sides (according to a division among clans), with the bereaved group receiving condolence from the other, which conducted mourning and burial rites and raised up a new chief. Grief could cause rash action that might imperil peace, and such condolence and requickening ceremonies—for common people as well as chiefs—restored calm and returned reason, locally and throughout Iroquoia.

In other matters, the League deliberated according to a tripartite arrangement, with discussion and proposed resolutions passing back and forth "across the fire" between the so-called Older Brothers (Mohawks and Senecas) and Younger Brothers (Oneidas and Cayugas), with the Onondagas, the firekeepers, mediating until the League forged its final, consensus decision. In some instances, the chiefs might find consensus difficult and prove unable to construct unified policy. In such cases, tribes and communities could act independently without compromising the integrity and efficacy of the League. And in fact the flexibility within this larger political or diplomatic structure was one of its strengths—except, that is, when the stakes were particularly high, Iroquois circumstances were constrained, and options were limited, as in the American Revolution.

In the early colonial period, the Five Nations found themselves geographically between expanding colonial powers in North America, as they straddled the frontiers of New France, New Netherland, and New England. The Iroquois transformed their potentially vulnerable position into an opportunity, as they found ways to mediate economically and diplomatically between both Natives and colonial newcomers. These colonial enterprises had been implanted atop an older Native political geography, which was reshaped by new colonial alliances, warfare, and especially epidemic diseases introduced unwittingly by European settlers. (Generally, Old World diseases reduced Native populations by an astonishing ninety percent within the first fifty years of sustained contact with colonists.)

Diplomatic skill, resourcefulness, some luck, and the influence of their League enabled the Five Nations to survive, despite population losses, as other Native peoples in the Northeast declined in numbers and power. After a series of conflicts in the seventeenth century, the Haudenosaunee brokered a peace with both the French and the English that established Iroquois neutrality and allowed them to play each power against the other until the demise of New France in 1763, following the French and Indian War.

Meanwhile, throughout the colonial period and beyond, the League of the Iroquois and its constituent nations absorbed refugee populations, integrating them as individual members of the five tribes, in some cases accepting them as allied and subordinate nations (as with the Stockbridge and Brotherton Indians among the Oneidas, or the Nanticokes and Tutelos among the Senecas and Cayugas in the Revolutionary era), or in the case of the Tuscaroras in the early eighteenth century as the sixth nation of the confederacy. The logic of the Iroquois League thus encouraged the extension of their great Longhouse, as the Haudenosaunee metaphorically removed the end-walls and built additions to accommodate new people, who were naturalized and amalgamated through marriage and reproduction, and who reinforced their social and political structure.

The Iroquois’ incorporation of other peoples could, however, be opportunistic or even at times coercive. Other Native groups were often unsettled by the impact of European colonialism and by the Iroquois themselves, and the Iroquois reacted to the shifting geopolitics of the region with force as well as diplomacy. But, as scholars have shown, the Iroquois did not establish an empire, nor did they seek colonial subjects; they proved expert at transforming former foes into family, foreigners into Iroquois, who became equal to those who had lived within the Longhouse since time immemorial.

Though famed as warriors in the eighteenth century, and reputed to control a huge backcountry "empire" encompassing hundreds of miles north to south along the Appalachian mountains, the Six Nations actually survived more through diplomacy and avoidance of warfare than through militarism. But then things changed. After Britain defeated France in North America in 1763, the Iroquois lost their ability to play one colonial power against another, and when hostilities erupted in the American Revolution, the Haudenosaunee found their mediating position dangerous and untenable.

Although both the Americans and the British initially advocated Six Nations’ neutrality, each ultimately pushed the Iroquois into the conflict, and the League failed to forge a consensus. Unable either to act in common or to avoid involvement, the League fractured. As its constituent nations found themselves on both sides, civil war loomed, and the council fire at Onondaga went out.

The war and its aftermath taxed the Iroquois’ ability to survive; to reconstruct their communities, economies, and polities; and to maintain their lands and sovereignty. The Haudenosaunee now resided in the new United States as well as British Canada, and two distinct Iroquois Leagues existed—one at Grand River in Ontario and the other at the rekindled council fire at Onondaga in New York. Dynamic changes washed through Iroquoia, with the expansion of the American republic and the encroachment of New York State, and a new prophet, Handsome Lake, arose among the Senecas, offering revitalization and a means to conserve Native identity and a measure of autonomy.

As Iroquois power declined, their League endured but evolved, offering the Haudenosaunee ongoing moral and political leadership vital to their survival. Ironically, the League of the Iroquois would continue to intrigue white Americans, who persisted in deploying their own fantastic understandings to serve their changing times and desires. In the late twentieth century, for example, the League was prominently misconstrued as the alleged prototype for the US Constitution. Those making the case believed their assertion showed respect and elevated the Iroquois "constitution" by linking it with the great chartering law of the United States. In fact, little evidence supports the link, and in any event the Iroquois League needs no such legitimation as it stands on its own as a vital and unique instrument for advancing the lives, liberty, and pursuits of happiness among the Haudenosaunee, from an ancient time into the present and the future.

[1] National Gazette (Philadelphia), April 5, 1792.

[2] DeWitt Clinton, "A Discourse Delivered before the New-York Historical Society, at their Anniversary Meeting, 6th December 1811," in Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1814 (New York: Van Winkle and Wiley, 1814), 2:44.

[3] [Portfolio,] "Sulphur Springs of New York," Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 13, no. 73 (June 1856): 1–17.

[4] William H. C. Hosmer, Yonnondio, or Warriors of the Genessee: A Tale of the Seventeenth Century (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1844), p. 7.

[5] John Galt, The Life, Studies, and Works of Benjamin West, Esq. (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies; and W. Blackwood, 1820), p. 105.

[6] Horatio Hale, ed., The Iroquois Book of Rites (Philadelphia: D. G. Brinton, 1883), pp. 75–76.

Matthew Dennis, a professor of history and environmental studies at the University of Oregon, has most recently published Seneca Possessed: Indians, Witchcraft, and Power in the Early American Republic (2010).