The Colonial Virginia Frontier and International Native American Diplomacy

by William White

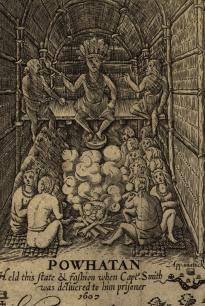

Telling the story of Native Americans and colonial Virginians is a complex challenge clouded by centuries of mythology. The history of early settlement is dominated by the story of a preteen Pocahontas saving the life of a courageous John Smith. Later, as a young woman, she is captured and held hostage by the English. This story ends with the powerful imagery of her conversion to Christianity, marriage to John Rolfe, and travel to and death in England. Popular media portray Pocahontas as a voluptuous cartoon character swimming in waterfalls, having conversations with animals, and becoming involved in a romantic liaison with the dashing John Smith. It is no wonder that Americans are uninformed about Virginia’s indigenous people. Even when we try, it is nearly impossible to shed the preconceived notions that inform the way we tell these stories.

Telling the story of Native Americans and colonial Virginians is a complex challenge clouded by centuries of mythology. The history of early settlement is dominated by the story of a preteen Pocahontas saving the life of a courageous John Smith. Later, as a young woman, she is captured and held hostage by the English. This story ends with the powerful imagery of her conversion to Christianity, marriage to John Rolfe, and travel to and death in England. Popular media portray Pocahontas as a voluptuous cartoon character swimming in waterfalls, having conversations with animals, and becoming involved in a romantic liaison with the dashing John Smith. It is no wonder that Americans are uninformed about Virginia’s indigenous people. Even when we try, it is nearly impossible to shed the preconceived notions that inform the way we tell these stories.

It is also important to understand that Virginia Indians were not a monolithic people. Pocahontas, her father Powhatan, and her uncle Opechancanough who figure so prominently in the Englishman’s story of settling Jamestown and the wars of 1622 and 1644 (what the English referred to as "massacres") do not represent the rich cultural variety of Virginia’s Native people. The coastal people we now call Powhatans were actually dozens of different peoples surrounded by more independent groups to their north, west, and south. The Native American nations who engaged with Virginians by the middle of the eighteenth century stretched from the Ohio River valley to the western lands of Kentucky to the frontiers of the Carolinas. We often refer to these nations as tribes today, but each had independence, political autonomy, and what we should think of as foreign policies designed to deal with other American Indian nations and with the European nations who were settling in North America. The story of the Native people who came in contact with colonial Virginians is a complex and layered story of diplomacy.

A large part of the challenge we face in understanding that complexity is due to the sources available to us as historians. Those sources are almost exclusively European documents that tell us how Europeans interpreted American Indian actions, and they are clouded with the Eurocentric assumption that Native society was savage and deficient. Increasingly, however, historians are uncovering the larger story of Native Americans and their agency from the documents, particularly translations of Native American speeches. It is a story of diverse peoples with complex interests pursuing the diplomatic goals of their own nations.

Take for example the Brafferton Indian School in at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. The 1693 charter for the college specified, among other things, that the institution was established so "that the Christian faith may be propagated amongst the Western Indians, to the glory of Almighty God." By 1723, the Brafferton building on campus was dedicated to the purpose. Young men were sent to the Brafferton, or Indian School, to be educated as Christian Englishmen. The hope on the part of the founders was that the students would return to their nations and act as agents of "civilization" and Christianization amongst their people.

The English had trouble filling the school. As one Iroquois chief politely noted, "We must let you know, we love our Children too well, to send them so great a Way, . . . We allow it to be good, and we thank you for the Invitation; but our Customs differing from yours, you will be so good as to excuse us."[1]

Nevertheless, Mattaponis, Pamunkeys, Chickahominys, Nansemonds, and others did attend. Evidence indicates that some tribes sent children for a specific purpose. While the English hoped to create agents for conversion and change amongst the American Indians, the Indians hoped to develop go-betweens or mediators between their people and their white neighbors.

One young man, who came to be known as John Nettles, was sent by the Catawbas to the Brafferton in the 1760s. He seemed to be a model student, yet when he returned to his people, the English were disappointed to see him readopt the cultural ways of the Catawbas. Still, the Catawbas teased Nettles for his Bible reading, his preference for English clothes, and his love of European dancing. But Nettles and his English education served the Catawbas well. For nearly 40 years he was the Catawbas’ translator, negotiator, and go-between. Nettles became a diplomat for his people.

Such diplomatic work was constant and complex. The Nottoways, Iroquois, Cherokees, Catawbas, and Shawnees sent frequent diplomatic missions to Williamsburg. In August 1751, for example, the Cherokees were in Williamsburg for at least a week negotiating a trade treaty with Virginia. The discussions went well. "You have supply’d all our Wants," the Cherokee representative was quoted as saying, "and we have nothing to desire but the Continuance of your Friendship." The friendship of the Virginia government, however, was not all that was at stake. Rumors circulated that the Nottoways were seeking to ambush the Cherokees to take revenge for the murder "many Years ago" of seven Nottoway young men.[2]

The situation became tense towards the end of the Cherokee visit when the Nottoways arrived in Williamsburg. On that morning the Cherokees made preparations to arm themselves and meet their adversaries, but several Virginia gentlemen apparently acted as mediators. The two groups met on the Market Square. After a series of negotiations, they concluded a peace agreement. The Nottoways produced a belt of wampum received from the Cherokees during their last peace negotiations and indicated that they "desired a Continuance of their Friendship." The Cherokee "Orator, who negotiates all their Treaties" noted that he had presented this wampum himself and accepted it back as a symbol of lasting friendship. The day that began with the threat of open conflict ended in peace.[3]

These complex interchanges made for a constantly shifting landscape for American Indians. By the eighteenth century trade goods were critical to Native culture. Diplomacy ensured that guns, gunpowder, steel axes and knives, iron pots, blankets, cloth and other essential commodities were available to them. By controlling portions of that trade, a nation could make itself more powerful and influential than its neighbors.

These relationships became even more complex during the 1750s when the British and French vied with each other to dominate the Ohio River Valley. While history books declare this a war against the French and the Indians, it is important to remember that there was not just one unified American Indian group. Diplomatic relationships stretched across many Native peoples, each with their own set of policy objectives intended not to support one European nation or the other, but rather to improve the condition of their own particular nations.

It is also critical to understand these diplomatic relationships were not only complex but also personal. Situations easily and quickly escalated, as was the case in 1774 with the start of what became known as Dunmore’s War.

A story told by the Mingo leader known to whites as Captain Logan describes the experience of Native Americans as well as European and African American settlers as they came in contact with each other on the frontier of Virginia.

I appeal to any white man to say that he ever entered Logan's cabin but I gave him meat; and he gave him not meat; that he ever came naked but I clothed him. In the course of the last war [French and Indian War], Logan remained in his cabin an advocate for peace. I had such an affection for the white people, that I was pointed at by the rest of my nation. I should have ever lived with them, had it not been for Colonel Cressop, who last year cut off, in cold blood, all the relations of Logan, not sparing women and children: There runs not a drop of my blood in the veins of any human creature. This called upon me for revenge; I have sought it, I have killed many and fully glutted my revenge. I am glad there is a prospect of peace, on account of the nation; but I beg you will not entertain a thought that any thing I have said proceeds from fear! Logan disdains the thought! He will not turn on his heel to save his life! Who is there to mourn for Logan? --- No one.[4]

Similar stories of frontier cooperation and betrayal were told over and over again among groups from 1607 into the nineteenth century. Sometimes it is an American Indian narrative. Sometimes it is a European or African American narrative. If we look carefully, Logan’s story tells us a great deal about the experience on the colonial Virginia frontier. It shows that the relationships among people were not usually or by necessity hostile. Logan fed and clothed white Virginians even during the French and Indian War. His affection for whites caused him to be singled out by his own people. Throughout the period, people of various cultures lived in proximity to each other. They helped each other, traded with each other, and forged advantageous alliances with each other. It was a relatively small world. People knew each other, called each other by name, and conducted personal relationships in a face-to-face world.

Consequently, when disagreements erupted into violence, the conflicts were often personal and specific. Logan’s story is an example of this. On May 3, 1774, a group of Virginians—one of whom Logan identified as a man named Colonel Cressop—enticed two men and two women across the Ohio River from their Mingo village and murdered them. When eight others from the Mingo village came searching they too were killed. Members of Logan’s family were among those murdered.

In the mid-eighteenth-century the Mingo people were forced westward into the Ohio River Valley by European settlements in the east. They lived in close proximity with other displaced peoples such as the Delawares and Shawnees. When his family was murdered, Logan demanded revenge. Young Shawnee men from a neighboring village sought to join him and advocated a major war, but the Shawnee chiefs managed to cool the situation. Still, a small number of Shawnees joined Logan’s war party.

Logan’s party of Mingos and Shawnees raided Pennsylvania and Virginia settlements on the frontier. They took thirteen scalps and sent hundreds of settlers fleeing eastward out of the back country. This act of revenge sparked a series of reactions. On the Virginia frontier such reactions had international consequences. There were dozens of Native American nations, each maintaining a complex set of diplomatic relationships with other Indian nations and with Europeans.

Logan’s revenge resulted in a diplomatic crisis. A substantial number of Shawnees protected white traders living in their country. The Shawnee chief Cornstalk sent a delegation to Fort Pitt, where they made clear that it was their intention to protect the traders. The Delawares living in the area owed their allegiance to the Six Nations of the Iroquois, and the Iroquois instructed their Delaware "brethren" to remove themselves from the territory and avoid the conflict. It was a clear diplomatic statement to militant Mingos and Shawnees that there would be no help from the Iroquois or their allies.

Meanwhile, frightened settlers demanded action and inflamed colonial public opinion against the Indians. Colonial governors felt obligated to respond. Though the governors of Pennsylvania and Virginia both ruled in the name of King George III, they represented very different interest groups and not a singular British policy. Each hoped to secure new western lands for their colonial constituencies. And in the case of Virginia, the governor, Lord Dunmore, was also an investor in land companies and would no doubt benefit personally from a successful western campaign against the Mingos and Shawnees.

The governor of Pennsylvania sent militia to attack Mingo and Shawnee villages in August 1774. Lord Dunmore led the militiamen to the frontier. By this time, Shawnee chiefs had no choice but to take up arms. On October 10, 1774, Virginians and Shawnee clashed at the Battle of Point Pleasant. The colonial forces continued to press into Shawnee territory until the Shawnees were forced to negotiate a peace. Among other things, the settlement required them to give up their hunting rights in Kentucky, revealing yet another consistent factor of the relationships between European and Native peoples: unrelenting pressure in the face of European migration and hunger for western lands.

It is easy to jump ahead in history to the early nineteenth century when Jacksonian Americans forced the removal of American Indian nations. From our perspective today, it seems obvious that Indian removal was the logical extension of British and later United States Indian policy. But when we examine colonial Virginia we must understand that the outcome was not obvious to the players at the time. Diplomacy—with its negotiations, personal and political relationships, and carefully considered and implemented policies in the face of evolving incidents and situations—was a critical tool of hope for the future amongst the Native American nations meeting European incursions and the complex challenges of their time along the frontier that was colonial Virginia.

[1] The Treaty held with the Indians of the Six Nations, at Lancaster, in Pennsylvania, in June, 1744, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1744, 68.

[2] The Virginia Gazette, Hunter edition, August 16, 1751, 3.

[3] The Virginia Gazette, Hunter edition, August 16, 1751, 3.

[4] The Virginia Gazette, Dixon edition, February 2, 1775, 3.

William E. White is the Royce R. & Kathryn M. Baker Vice President of Productions, Publications, and Learning Ventures for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. He leads the Colonial Williamsburg Teacher Development initiative, the Emmy-winning Electronic Field Trip series, and is the author of Colonial Williamsburg’s high school American history curriculum, The Idea of America.