From the Editor

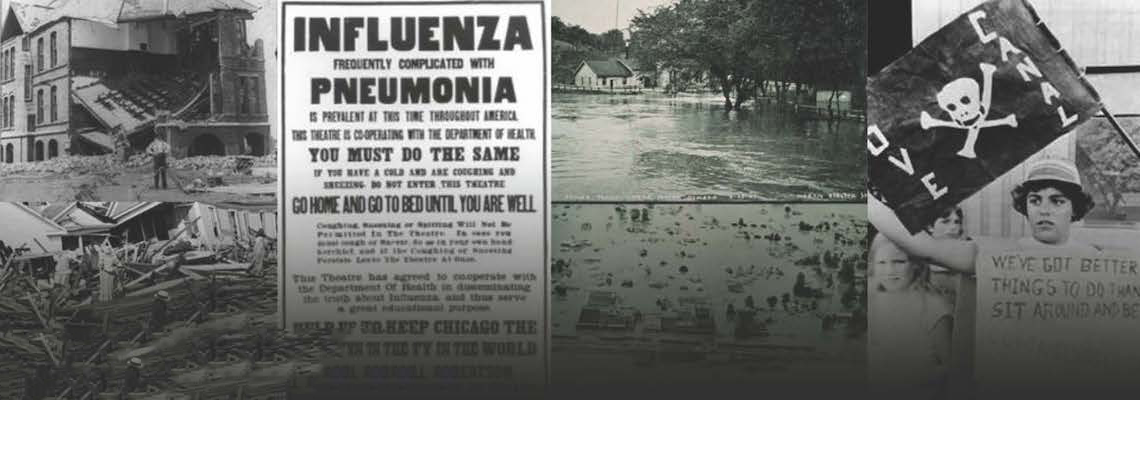

Sharks raining down on Los Angeles, zombies menacing their neighbors, strange aliens invading earth’s cities, prehistoric creatures chasing shipwrecked travelers . . . Americans thrill to stories of disaster. Whether man-made or natural, these disasters can be enjoyed because they are fantasies. But modern American history offers us evidence of very real disasters, made more terrible because they often are a deadly combination of natural phenomena and human actions. In this issue of History Now, scholars examine the causes and consequences of four memorable disasters.

In his overview essay, "Disasters and the Politics of Memory," Kevin Rozario uses 9/11 to illustrate our longstanding desire to document, memorialize, and draw lessons from events that fascinate and sadden. As Rozario points out, however, the interpretation of disasters by museums and memorials is often shaped by a desire to focus on heroism and community solidarity while avoiding the political and commercial aspects of events like 9/11 or the ethnic and class bias of relief aid to those who suffered.

In "One of Those Monstrosities of Nature," Elizabeth Hayes Turner looks at the Galveston Storm of 1900. Although this island city had done much to guard against devastation by hurricanes and storms, raising sidewalks and building homes on pilings to avoid the effects of flooding, the ferocity of the storm took most residents by surprise. Many were unable to reach their homes; others sought refuge in public buildings. The storm left thousands dead, especially working-class men, women, and children. In the wake of the flood, new civic organizations were created, including a community relief initiative, a Women’s Health Protective Association, and a black Red Cross Auxiliary. As Turner notes, racial and class cooperation contributed to Galveston’s economic recovery.

Carol Byerly explores the impact of disease in her essay, "The Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919." Tracing its first sign in America with a sick call at an army camp, Byerly carries us through a pandemic that ultimately sickened a quarter of the world’s population and led to the death of an estimated 50 million people. Without the antibiotics available today to fight the disease, doctors could do little but prescribe bed rest and aspirin. The disease dramatically reduced the number of allied and German soldiers in the field during World War I. Yet in popular memory the horrors of that war seemed to eclipse the flu that carried millions across the world to their graves.

In "The Great Mississippi River Flood," John M. Barry examines the disaster caused by torrential rains and river flooding in middle America. The damage caused by heavy rainfall and rising rivers beginning in September 1926 was immediate and extensive: towns were flooded, crops ruined, and people killed. In the spring of 1927, the entire Mississippi River system spilled over its banks, killing nearby residents from Virginia to Oklahoma. The legacy of the flood was far reaching, changing the technology used in river control, contributing to the election of President Herbert Hoover, and altering Americans’ view of the government’s responsibility in the face of natural disasters.

Finally, in "Everyone’s Backyard: The Love Canal Chemical Disaster," Amy Hay focuses on a disaster created not by nature, but by corporate and government disregard for the health and safety of communities. The environmental calamity created by the dumping of toxic waste began to be recognized in the spring of 1978 when EPA officials appeared on the streets of a Niagara Falls neighborhood. Residents near Love Canal organized informally at first, but later formed a Homeowners’ Association that pressured the government to protect the value of their homes and their ability to produce healthy children. Here, race and class influenced the actions taken by Love Canal victims, for the homeowners were white and the renters in the nearby housing project were African American. The Love Canal scandal led to new legislation, tighter regulations on the disposal of hazardous materials, and a growing recognition that environmental risk could be the result of human choices and activities.

In this issue, as in all issues of History Now, you will find lesson plans for middle and high school classes. Our interactive feature is a timeline with illustrations charting the disasters our scholars have discussed.

We wish all teachers a satisfying and successful new school year—and hope all our readers will come away from this issue with a deeper understanding of the many causes and consequences of the disasters we face.

Look for our next issue, in January, which will explore the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and its impact on modern American society.

![]()

Carol Berkin

Related Resources

From the Archives

Essays

- San Francisco and the Great Earthquake of 1906, by Robert W. Cherny