The Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919

by Carol Byerly

On September 19, 1918, 21-year-old Army private Roscoe Vaughan reported to sick call at Camp Jackson, South Carolina, feeling achy and feverish. He was promptly hospitalized along with eighty-two other soldiers that day. Influenza had reached the camp only the day before and would send 1,000 men to the hospital within a week. Medical officers at Camp Jackson implemented a special treatment program for respiratory diseases, holding sick call twice a day to examine the men for the flu and sending anyone with a temperature over 100 degrees to the hospital. Despite their efforts, influenza sickened more than 10,000 of the 38,000 men in the camp, killing 400, including five nurses who were caring for the soldiers. Private Vaughan was one of the unlucky ones who developed pneumonia; he died on September 26, just weeks after he had left home to join the Army. Captain K. P. Hegeforth performed an autopsy on the young man, excising a piece of his sodden lung and preserving it in formaldehyde and wax. This he sent to Washington for analysis and cataloguing at the Army Medical Museum where scientists were trying to understand the nature of the killer.

On September 19, 1918, 21-year-old Army private Roscoe Vaughan reported to sick call at Camp Jackson, South Carolina, feeling achy and feverish. He was promptly hospitalized along with eighty-two other soldiers that day. Influenza had reached the camp only the day before and would send 1,000 men to the hospital within a week. Medical officers at Camp Jackson implemented a special treatment program for respiratory diseases, holding sick call twice a day to examine the men for the flu and sending anyone with a temperature over 100 degrees to the hospital. Despite their efforts, influenza sickened more than 10,000 of the 38,000 men in the camp, killing 400, including five nurses who were caring for the soldiers. Private Vaughan was one of the unlucky ones who developed pneumonia; he died on September 26, just weeks after he had left home to join the Army. Captain K. P. Hegeforth performed an autopsy on the young man, excising a piece of his sodden lung and preserving it in formaldehyde and wax. This he sent to Washington for analysis and cataloguing at the Army Medical Museum where scientists were trying to understand the nature of the killer.

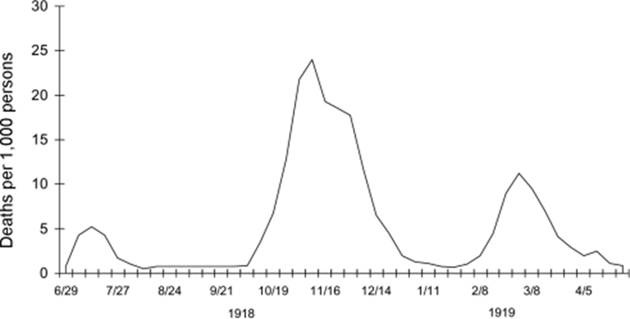

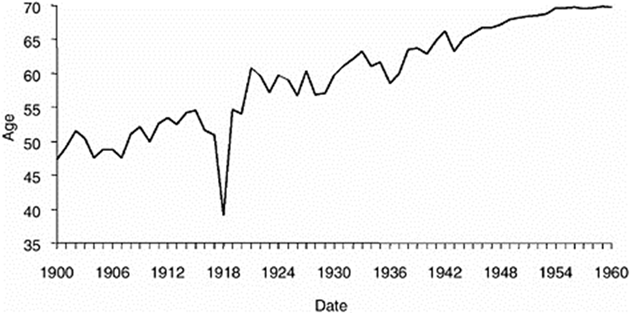

Roscoe Vaughan was a victim of one of the deadliest disasters in human history. Coming on the heels of World War I (1914–1918), influenza followed wartime transportation routes across oceans and continents, sickening at least one-quarter of the world’s population and killing an estimated fifty million people in just eighteen months.  This figure far exceeded the toll of twelve to sixteen million wartime casualties. The influenza outbreak devastated a world already struggling with the mass death and destruction wrought by more than four years of modern industrial warfare. The pandemic came in three waves, the first in the spring of 1918, the second and most deadly wave in the late summer and fall, and the third weakened but still lethal wave in early 1919. In the United States an estimated twenty-five million people became ill and 675,000 died. The disaster was so powerful in 1918 that it reduced American life expectancy statistics by almost twelve years.

This figure far exceeded the toll of twelve to sixteen million wartime casualties. The influenza outbreak devastated a world already struggling with the mass death and destruction wrought by more than four years of modern industrial warfare. The pandemic came in three waves, the first in the spring of 1918, the second and most deadly wave in the late summer and fall, and the third weakened but still lethal wave in early 1919. In the United States an estimated twenty-five million people became ill and 675,000 died. The disaster was so powerful in 1918 that it reduced American life expectancy statistics by almost twelve years.

The origin of the influenza of 1918 has long been a mystery. The prevailing theory is that it first appeared in the American Midwest in March 1918 and spread to soldiers in training camps across the country where medical officers reported high influenza rates but few deaths. The virus then traveled to Europe, probably aboard troopships, to the Western Front where in May and June it sickened thousands of soldiers but killed few in this first wave. In the wretched conditions of trench warfare, however, the virus flourished, mutating into an especially virulent strain that exploded worldwide in August 1918. This deadly second wave of flu appeared simultaneously in the ports of Boston, Brest (France), and Freetown (Sierra Leone), once again following the troops and trade generated by the war, spreading throughout the globe within weeks. Contemporaries began calling it "Spanish influenza" because Spain was one of the few countries not at war and therefore did not censor reports of illness within its borders.

The origin of the influenza of 1918 has long been a mystery. The prevailing theory is that it first appeared in the American Midwest in March 1918 and spread to soldiers in training camps across the country where medical officers reported high influenza rates but few deaths. The virus then traveled to Europe, probably aboard troopships, to the Western Front where in May and June it sickened thousands of soldiers but killed few in this first wave. In the wretched conditions of trench warfare, however, the virus flourished, mutating into an especially virulent strain that exploded worldwide in August 1918. This deadly second wave of flu appeared simultaneously in the ports of Boston, Brest (France), and Freetown (Sierra Leone), once again following the troops and trade generated by the war, spreading throughout the globe within weeks. Contemporaries began calling it "Spanish influenza" because Spain was one of the few countries not at war and therefore did not censor reports of illness within its borders.

Like the common flu, the 1918 influenza had a short incubation period and a high sickness rate. It spread easily from person to person, most often in airborne droplets. This virus, however, had unusually severe symptoms. Some medical personnel described an "explosive" onset of illness characterized by high fever, exhaustion, severe headaches, nosebleeds, a blood-producing cough, and cyanosis—a blueish cast to the skin caused by lack of oxygen in the blood. Army medical officer George Soper observed, "The onset is sudden. The patient can often tell the exact moment of his attack. In the typical case he is very sick – wholly incapacitated for exertion. He lies curled up and can hardly be roused for food."

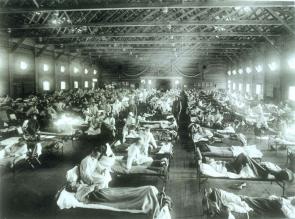

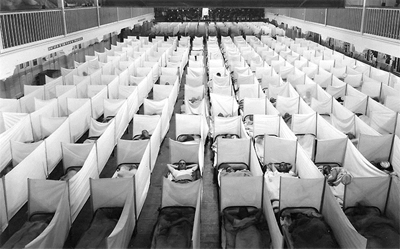

Given the short incubation period, historians can track the spread of the influenza virus with precision. Navy surgeons pinpointed its arrival in the United States to August 27 at Commonwealth Pier in Boston, with three cases of influenza. Influenza then spread to army trainees at nearby Camp Devens, Massachusetts, the week of September 7, and from there swept the country south and west, following wartime transportation routes, striking civilian and military localities alike. It hit Kansas on September 21, then northern California and Texas on September 27. By the week of October 16 the epidemic was nationwide. Sickness rates averaged 25 percent but varied widely, from 15 percent of residents in Louisville, Kentucky, for example, to a staggering 53 percent in San Antonio, Texas. When influenza reached a locality, it often caused social paralysis, sending thousands of people to bed pale and helpless. Influenza victims flooded hospitals, crowded morgues and cemeteries, and caused officials to close schools, government offices, stores, theaters, and churches in an effort to prevent the spread of the disease. As medical professionals fell sick, many communities faced critical personnel shortages and had to recruit medical workers out of retirement or training schools. Epidemic influenza, which lasted about four weeks in individual communities, prevailed in the United States roughly from September 15 to November 15.

Given the short incubation period, historians can track the spread of the influenza virus with precision. Navy surgeons pinpointed its arrival in the United States to August 27 at Commonwealth Pier in Boston, with three cases of influenza. Influenza then spread to army trainees at nearby Camp Devens, Massachusetts, the week of September 7, and from there swept the country south and west, following wartime transportation routes, striking civilian and military localities alike. It hit Kansas on September 21, then northern California and Texas on September 27. By the week of October 16 the epidemic was nationwide. Sickness rates averaged 25 percent but varied widely, from 15 percent of residents in Louisville, Kentucky, for example, to a staggering 53 percent in San Antonio, Texas. When influenza reached a locality, it often caused social paralysis, sending thousands of people to bed pale and helpless. Influenza victims flooded hospitals, crowded morgues and cemeteries, and caused officials to close schools, government offices, stores, theaters, and churches in an effort to prevent the spread of the disease. As medical professionals fell sick, many communities faced critical personnel shortages and had to recruit medical workers out of retirement or training schools. Epidemic influenza, which lasted about four weeks in individual communities, prevailed in the United States roughly from September 15 to November 15.

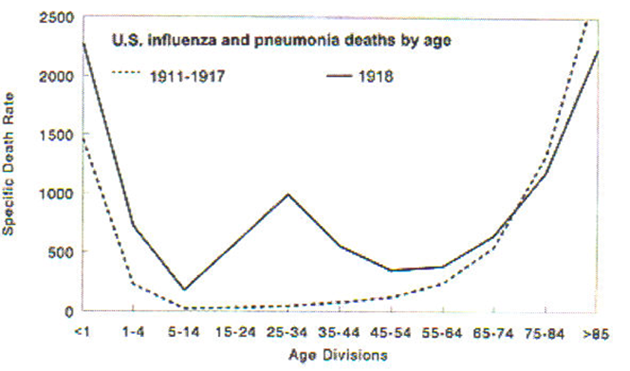

Influenza usually kills only the very weak in a population—the youngest and the oldest people—creating a "U-shape" mortality curve. The 1918 virus was especially deadly, however, for people aged twenty to forty, producing what was a "terrible W" curve of high mortality for the young and old at the extremes of the demographic spectrum, with an unusual peak at its center.  Recent research suggests that the deadliness of the 1918 virus resulted from its ability to penetrate deep into the lung tissue, which caused some victims to succumb quickly to viral pneumonia. The majority, however, died after a longer period from secondary pneumonia caused by a variety of bacteria, including pneumococci, streptococci, and staphylococci. Some scientists theorize that the viral attack stimulated such a strong immune response that people with especially robust immune systems—such as young adults—released so many antitoxins or cytokines to fight it that the fluids flooded the lungs, producing pneumonia.

Recent research suggests that the deadliness of the 1918 virus resulted from its ability to penetrate deep into the lung tissue, which caused some victims to succumb quickly to viral pneumonia. The majority, however, died after a longer period from secondary pneumonia caused by a variety of bacteria, including pneumococci, streptococci, and staphylococci. Some scientists theorize that the viral attack stimulated such a strong immune response that people with especially robust immune systems—such as young adults—released so many antitoxins or cytokines to fight it that the fluids flooded the lungs, producing pneumonia.

Medical professionals did their best to save flu patients, but in an era before virology and antibiotics, they lacked effective tools. Treatment included bed rest, a light diet, aspirin for fever and pain, and warmth to keep the patient from developing pneumonia. Both military and civilian care-givers also tried whiskey, patent medicines, a range of home remedies, and injections of various serums. Preventive measures included the wearing of masks and the use of throat and nasal sprays and myriad vaccines, but short of a complete, prolonged quarantine, nothing worked. Most patients recovered after a few days, but if they developed pneumonia they could suffer permanent lung damage, experience mental symptoms such as prolonged fatigue, depression, and anxiety, or face imminent death.

The impact of the pandemic on World War I is still being weighed. In Europe, influenza attacked the Allied and German armies with equal virulence, filling field hospitals and medical transports with weak, feverish men all along the Western Front. In October 1918, at the height of the American Expeditionary Force’s Meuse-Argonne offensive, influenza dramatically reduced the number of soldiers who could fight and overwhelmed medical services. It took a toll on US war mobilization, undermining Army training and transport plans and depleting the domestic labor force so dramatically that some war industries and mines had to suspend operations. The War Department took steps to control the epidemic in the training camps, but so many new recruits were entering the camps and falling ill, the Army Provost Marshall had to cancel the October 1918 draft call. By the War Department’s most conservative count influenza sickened 26 percent of the Army—more than one million men—and killed 30,000 men in training camps before they even got to France. The Army lost a staggering 8,743,102 work-days to influenza among enlisted men in 1918 and the Navy calculated the sickness rate as 40 percent of 600,000 men. Thus, despite the lethality of modern weapons of war, more American soldiers died of disease than in combat during World War I.

By mid-November the flu had subsided in Europe, but reappeared in January and February 1919 and sickened participants at the Paris Peace Conference. This third wave, less powerful but still deadly, again swept the globe, but by mid-1919 influenza had probably infected almost all susceptible hosts and thus either evolved to a more benign form or burned out. As the world struggled to recover from the horror of World War I, it seemed to forget about the influenza pandemic. For decades the most enduring signs of the disaster were the gravestones of young-adult victims in cemeteries worldwide.

Influenza epidemics emerge periodically in the human population and public health officials continue to monitor the ever-evolving flu virus, on the lookout for another deadly strain. Almost eighty years after Roscoe Vaughan succumbed to influenzal pneumonia, scientists at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology analyzed the tissue sample taken from his lungs using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) process, and in 1997 were able to identify the influenza virus of 1918–1919 as type A, H1N1. In the event of an outbreak of another virulent strain, such knowledge will help scientists to develop prophylactic vaccines as well as viral therapies and antibiotics, which might help to control the spread of disease and death. But the influenza pandemic of 1918–1919 stands as a cautionary tale of the power of disease to wreak havoc on human society.

Further Reading

Bristow, Nancy. American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Byerly, Carol R. The Fever of War: The Influenza Epidemic in the U. S. During World War I. New York: New York University Press, 2005.

Crosby, Alfred. America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Lezzoni, Lynette. Influenza 1918: The Worst Epidemic in American History. New York: TV Books, 1999. This is the companion book to television documentary "Influenza 1918," from the PBS television documentary series The American Experience.

Kent, Susan K. The Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919. Bedford Series in History and Culture. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2012.

Kolata, Gina. Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus that Caused It. New York: Farrar Straus, and Giroux, 1999.

War Department. Office of the Surgeon General. Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1921–29, volumes 1–15.

"The 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic in the United States," Public Health Reports, volume 125, supplement 3, (April 2010): 1–144.

Carol Byerly teaches history at the University of Colorado, Boulder. A specialist in the field of military medicine, she is the author of Fever of War: The Influenza in the US Army during WWI (New York University Press, 2005).