From The Editor

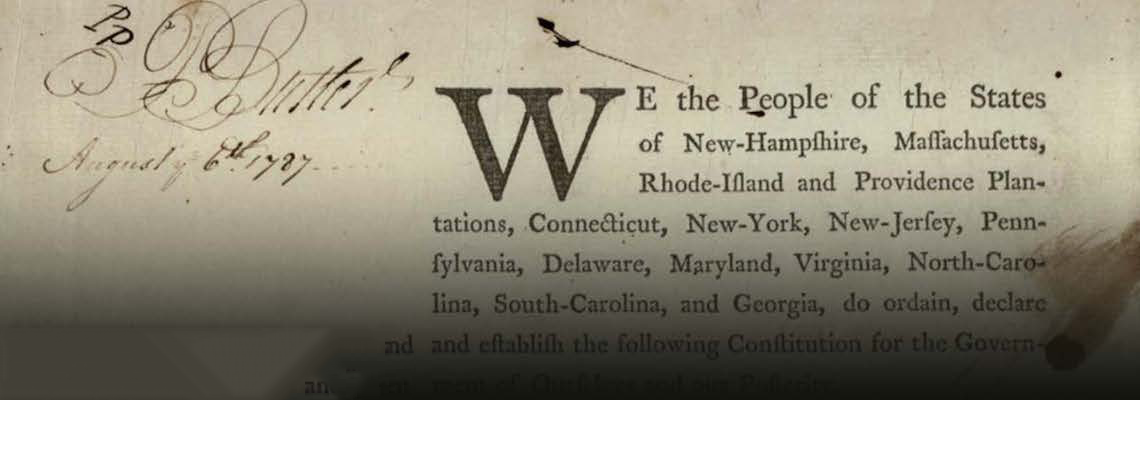

When delegates from twelve states gathered in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, many of them feared that the quarrels between the states, the sudden rash of internal rebellions, the continuing presence of enemies on our national borders, the embarrassing debts owed to foreign nations and to our own citizens, and the vulnerability of our merchant marine on the oceans all spelled doom for the young republic. The new frame of government that these political leaders produced was thus born in crisis— but it proved capable of surviving that crisis and many others to come in the nation's future.

In this issue of History Now, our scholars and teachers explore the philosophical and political traditions and innovations that defined the Constitution and those that prompted opposition to it by the Antifederalists. They look at the social context in which the constitution was created—and discuss the groups that the delegates failed to grant the same equality and freedom that they cherished for themselves. The result is a rich, in-depth examination of the Constitution— its strengths and its flaws. These essays remind us and our students that the endurance of the Constitution is a tribute to the framers’ willingness to see it change as American society itself changed, to adjust to the needs of future generations that these men, wise though they were, could not foresee.

Constitutional scholar Linda R. Monk’s "Why We the People? Citizens as Agents of Constitutional Change" introduces us to one of the most radical ideas embodied in the Constitution: that ultimate sovereignty lies with the citizens themselves. It was this principle, Monk reminds us, that prompted the demand, during the ratification debates, that a bill of rights be added to the Constitution. She shows us that later generations of propertyless men, white women, African Americans, and Indians would rely on the promise of these rights as they fought for inclusion into the ranks of "we the people." In his essay "James Madison and the Constitution," Professor Jack Rakove probes the mind of James Madison -- the delegate known as the "architect of the Constitution," explores the weaknesses of the Articles government, and develops arguments for a stronger union in a memorandum entitled Vices of the Political System of the United States. Madison’s brilliant analysis of the problems facing the new republic formed the basis for the plan he would bring to the constitutional convention in 1787. In "The Antifederalists: The Other Founders of the American Constitutional Tradition?" Professor Saul Cornell helps us understand that the dissenting voices of the Antifederalists are a critical part of our political heritage. The issues these men raised—in the ratifying conventions and in the press—were serious ones: the omission of a bill of rights, the centralizing tendencies of the new government, and what they feared was its aristocratic character. These concerns brought together rich men and poor, northerners and southerners, farmers and planters and artisans. The glue that bound them together was a desire to protect individual rights and local interests. In "Ordinary Americans and the Constitution," Professor Gary Nash explores the views of African Americans, artisans, and small farmers—groups who opposed the Constitution because it denied them rights or ignored their interests. As Nash shows us, these groups would continue to stand as critics of the Constitution throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century as long as it failed to recognize their equality. Professor James O. Horton continues this theme in his essay "Race and The American Constitution: A Struggle Toward National Ideals." Horton traces the long and difficult struggle by African Americans, free and enslaved, to gain recognition as full citizens of the United States. Their struggle tested the ideals of the founding generation—and exposed the racial assumptions and prejudices not only of the framers but of later generations of Americans. Finally, Theodore Crackel, editor of the George Washington Papers, gives us a thoughtful look at one of our most cherished heroes, the Commander in Chief of the Continental Army, the presiding officer at the constitutional convention, and the first president of the United States. Crackel shows us how Washington’s experiences as Commander in Chief gave him a nationalist rather than a provincial perspective. He also shows us how important Washington’s support for the new constitution proved to be. And, perhaps most importantly, he shows us the judiciousness and care with which the first president administered his office, always recognizing that his actions would set a precedent for executives to come.

As Constitution Day projects and lessons begin across the country, these essays should prove an excellent starting point for students and teachers alike. In addition, our archivist Mary-Jo Kline provides a wealth of source materials for further study and our master teachers provide lesson plans for classrooms at high school, middle and elementary school levels, and our interactive feature for this issue is a quiz on Constitutional trivia.

We are also proud to present a new feature in this issue of History Now: four book reviews by two classroom teachers, focusing on two scholarly books for your own background reading and two books that our reviewers feel might be useful in the classroom itself.

As always, we welcome your comments and suggestions—and hope you will share your ideas for lessons or projects with your peers across the country through the pages of History Now.

Carol Berkin

Editor, History Now

Carol Berkin is Presidential Distinguished Professor of History at Baruch College and The Graduate Center, City University of New York. She is the author of several books including Jonathan Sewall: Odyssey of an American Conservative, First Generations: Women in Colonial America, A Brilliant Solution: Inventing the American Constitution, and Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America's Independence.