Why We the People? Citizens as Agents of Constitutional Change

by Linda R. Monk

"We the People?" asked Patrick Henry at the Virginia convention to ratify the new Constitution in 1788. "Who authorized them to speak the language of ‘We the People,’ instead of ‘We the States’?"[1] Looking back, we can be grateful that Henry did not attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia—and not just because of his views on federalism. Without a government based on the power of the people to effect change, the US Constitution would not have endured for the past 220 years.

"We the People?" asked Patrick Henry at the Virginia convention to ratify the new Constitution in 1788. "Who authorized them to speak the language of ‘We the People,’ instead of ‘We the States’?"[1] Looking back, we can be grateful that Henry did not attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia—and not just because of his views on federalism. Without a government based on the power of the people to effect change, the US Constitution would not have endured for the past 220 years.

A simple declarative sentence is at the heart of the world's oldest written constitution of a nation that is still in effect: "We the People . . . do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America." All other dependent clauses in the Preamble explain why the Constitution was written, but they are not necessary. Subject, verb, object: those three elements determine where the action is in a sentence, and in this case, a government. The verb is present-tense, not past. It is active, not passive. I believe this phrasing implies an ongoing obligation of citizens to be actors in constitutional government. As University of Oregon law professor Garrett Epps has said: "Every morning we wake up and decide that we want to live in a constitutional republic."[2]

Yet scholars tend to focus on the three branches of government created by the Constitution instead of the foundation upon which they rest: an active citizenry. The history of civic movements is a necessary element of understanding constitutional change and recognizing the limits of any government institution. Three examples from constitutional history help prove this point; the creation of the Bill of Rights; the expansion of suffrage; and the modern Civil Rights Movement.

I. What No Government Should Rest on Inference

Today, we refer to the 1787 convention in Philadelphia as the Constitutional Convention because we know the final outcome, but at the time it was known as the Federal Convention and its deliberations were secret. The windows of Independence Hall, as we refer to it now, were kept tightly shut to prevent nosy reporters from eavesdropping on the deliberations—this in an age without air conditioning or deodorant. On top of that, in 1787 Philadelphia was infested with an invasion of black flies, the worst many natives had ever seen.

The fifty-five men who gathered in Philadelphia during that hot summer had a sense of failure as well as promise. The American colonies had declared their independence from Britain in the very same building a decade earlier, but they had yet to prove they could maintain a stable form of government. As George Washington noted in frustration from his retirement at Mount Vernon: "What a triumph for the advocates of despotism to find that we are incapable of governing ourselves."[3]

Yet the Constitution produced by this assembly of the ablest leaders in America did not include what most Americans today view as indispensable: a bill of rights. Did the framers just forget? No, delegate George Mason of Virginia, the legendary author of Virginia’s landmark Declaration of Rights in 1776, made an unsuccessful motion to add a bill of rights before the Constitution was completed. Mason, a man not known for intemperance, declared at the convention that he would "sooner chop off his right hand than set it to the Constitution as it now stands."[4] George Washington, his lifelong friend, never forgave Mason for his opposition to the Constitution.

But the people of Virginia and elsewhere in the nation vindicated Mason’s stand. The Federalist supporters of the Constitution, like James Madison, quickly realized that without a bill of rights, the people would not agree to ratify the Constitution. As Thomas Jefferson wrote to Madison from Paris, "a bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth" and "what no just government should refuse or rest on inference."[5]

The people got their Bill of Rights, thanks to James Madison keeping his political promise to the voters of Virginia when they elected him to the first Congress. The adoption of the Bill of Rights was the lasting legacy of Revolutionary farmers and their Antifederalist movement, which feared the powers of a strong national government. It set a powerful precedent for the role of citizens in creating constitutional change.

II. Which "We the People"?

Who are "We the People"? This question troubled the nation for centuries. As legendary orator Lucy Stone, one of America’s first advocates for women’s rights, asked in 1853: "‘We the People’? Which ‘We the People’? The women were not included."[6] Neither were white males who did not own property, American Indians, or African Americans—slave or free. Yet, one by one, these groups were eventually brought within the Constitution’s definition of "We the People" through civic movements dedicated to that purpose.

White men without property sought the right to vote after the Constitution was adopted. John Adams fought this movement, arguing that men without property were dependent, like women and children, and could not exercise an independent ballot. Give men without property the ballot, said Adams, and the next thing you know women and children would want one, too. Benjamin Franklin countered this argument with a story about a man and a jackass:

Today a man owns a jackass worth fifty dollars and he is entitled to vote; but before the next election the jackass dies. The man in the meantime has become more experienced, his knowledge of the principles of government and his acquaintance with mankind are more extensive, and he is therefore better qualified to make a proper selection of rulers—but the jackass is dead and the man cannot vote. Now, gentlemen, pray inform me, in whom is the right of suffrage? In the man or the jackass?[7]

This question was ultimately answered by state governments, which faced the democratic tides of the Jacksonian era. But another group of people lost their constitutional rights as a result. During the 1830s, the Cherokee Nation argued that American Indians were protected under the Constitution. The Cherokees issued a protest to Congress when President Andrew Jackson, reflecting the political power of newly enfranchised and land-hungry whites, would not enforce a Supreme Court decision upholding their property rights. The Cherokee wrote:

For more than seven long years have the Cherokee people been driven into the necessity of contending for their just rights, and they have struggled against fearful odds. . . . Their resources and means of defense have been seized and withheld. The treaties, laws, and Constitution of the United States, their bulwark and only citadel of refuge, put beyond their reach.[8]

President Jackson is rumored to have responded to the Supreme Court’s ruling in favor of the Cherokees: "John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it." Whether or not Jackson actually uttered those words, his actions proved the statement true. Jackson opposed Marbury v. Madison and the power of judicial review. He believed that as president he had an independent power to decide what the Constitution meant, at least for the executive branch.

Under the Indian Removal Act of 1830, Jackson had begun the process of relocating five nations of Native Americans from their ancestral lands in the Southeast to what is today the state of Oklahoma. In 1838, in an act that might today be regarded as ethnic cleansing, the US Army was ordered to forcibly march 16,000 Cherokees to reservations in the West. One-fourth died on that "Trail of Tears." Only in 1924 were Native Americans finally given full citizenship under the Constitution, by act of Congress.

African Americans also sought to be included in the Constitution’s definition of "We the People." Frederick Douglass, a former slave and brilliant abolitionist orator, wrote in 1857, in reaction to the Dred Scott decision that held African Americans, free or slave, could never be citizens:

We, the people—not we, the white people—not we, the citizens, or the legal voters—not we, the privileged class, and excluding all other classes but we, the people, not we, the horses and cattle, but we the people—the men and women, the human inhabitants of the United States, do ordain and establish this Constitution.[9]

Chief Justice Roger Taney’s decision in Dred Scott precipitated a civil war instead of averting it, as President James Buchanan—who actively lobbied the Court—had hoped. Out of that crucible came the Fourteenth Amendment, which made African Americans full citizens—at least on paper. Yet it would be another century before African Americans would begin to enjoy anything approaching "equal protection of the law."

Women were active in the abolitionist movement from the very beginning, and many abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, supported equal rights for women. Susan B. Anthony, who campaigned for women’s suffrage, echoed Douglass’s definition of "We the People" when she wrote in 1872:

It was we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union. And we formed it, not to give the blessings of liberty, but to secure them; not to the half of ourselves and the half of our posterity, but to the whole people—women as well as men.[10]

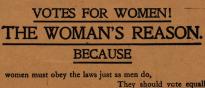

Litigation to apply the Fourteenth Amendment’s protections to women failed. It was direct action against the White House during World War I that finally turned the tide for women’s suffrage. Sign-toting suffragists asked, "Mr. President, How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?" Their leader, Alice Paul, was arrested along with others for chaining themselves to the White House fence and force-fed during a prison hunger strike—while women in countries the US was fighting against already had the right to vote.

Through the amendment process, and the civic movements that demanded such amendments, more Americans were eventually included in the Constitution’s definition of "We the People." After the Civil War, the Thirteenth Amendment ended slavery, the Fourteenth Amendment gave African Americans citizenship, and the Fifteenth Amendment gave black men the vote. In 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment gave women the right to vote nationwide, and in 1971 the Twenty-sixth Amendment extended suffrage to eighteen year-olds. But these amendments were impossible without an abolitionist movement that swayed Lincoln, a women’s suffrage movement that accused Woodrow Wilson of being a hypocrite about democracy, and a youth movement that insisted someone old enough to die for his government was also old enough to elect it.

III. Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired

This September marks the fiftieth anniversary of President Dwight Eisenhower’s deployment of the 101st Airborne Division to enforce a federal court order desegregating Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas. It’s hard to imagine a more emphatic use of executive power in support of judicial review—exactly what Andrew Jackson refused to do for the Cherokees. Yet the schools in Little Rock closed the next year rather than admit black students. In Virginia, a state system of "massive resistance" to integration closed schools for some black children more than five years, prompting a recent state settlement to them as adults.

What changed? The states clearly called President Eisenhower’s bluff, realizing that he could not use armed forces to carry out court orders in every school district. Why then are today’s schools lawfully required to admit all students, regardless of race? My answer, as a constitutional scholar, is that enough Americans of all races decided that they were "sick and tired of being sick and tired," in the words of my personal heroine, Fannie Lou Hamer.[11] An African American sharecropper in my native state of Mississippi, Mrs. Hamer became a national leader in the Civil Rights Movement because she had the moral courage to face down segregationists and get beaten as a consequence. Thousands more like her filled jails all across the American South.

The modern Civil Rights Movement proved that monumental change, while difficult, could be achieved by a group of determined citizens—even when the Congress, the president, and the Supreme Court could not guarantee the outcome. Government institutions, in the end, are limited or empowered by the people upon whose authority they rest. The great judge Learned Hand highlighted this dilemma during World War II in his famous speech, "The Spirit of Liberty." As Judge Hand knew, Nazi Germany had a constitution, and laws, and courts, but that did not ensure freedom. He said:

I often wonder whether we do not rest our hopes too much upon constitutions, upon laws, and upon courts. These are false hopes; believe me, these are false hopes. Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it.[12]

George Washington echoed this reality when he wrote Patrick Henry to persuade him to support the new Constitution. Washington admitted that the Constitution was not perfect, but rather perfectible through the amendment process. "I wish the Constitution which is offered had been made more perfect, but I sincerely believe it is the best that could be obtained at this time; and . . . a constitutional door is opened for amendment hereafter."[13] Article V provided a means through which We the People, as citizens, could repeatedly assert our authority to "ordain and establish" this Constitution. And that, as the poet says, has made all the difference.

[1] Bernard Bailyn, ed., The Debate on the Constitution, Part Two (New York: Library of America, 1993), 596.

[2] David Ignatius, "Not Their Finest Hour," Washington Post, November 12, 2000, B7.

[3] W.W. Abbot, ed., The Papers of George Washington: Confederation Series (Charlottesville: University of Virigina Press, 1992), 4:213.

[4] Adrienne, Koch, ed., Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 Reported by James Madison (New York: W. W. Norton, 1987), 566.

[5] Merrill Peterson, ed., Thomas Jefferson: Writings (New York: Library of America, 1984), 916.

[6] Linda Monk, The Words We Live By: Your Annotated Guide to the Constitution (New York: Hyperion, 2003), 12.

[7] Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (New York: Basic Books, 2000), 3.

[8] Linda Monk, ed., Ordinary Americans: U.S. History Through the Eyes of Everyday People (Alexandria, Va.: Close Up Publishing, 1993), 51–52.

[9] Philip S. Foner, ed., Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, Vol. 2 (New York: International Publishers, 1950), 419.

[10] Diane Ravitch and Abigail Thernstrom, eds., The Democracy Reader (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 167–68.

[11] Linda R. Monk, The Bill of Rights: A User’s Guide, 4th ed. (Alexandria, Va.: Close Up Publishing, 2003), 228.

[12] Linda R. Monk, The Words We Live By: Your Annotated Guide to the Constitution (New York: Hyperion, 2003), 9.

[13] Michael Kammen, ed., The Origins of the American Constitution: A Documentary History (New York: Penguin, 1986), 56.

Linda R. Monk is the author of The Words We Live By: Your Annotated Guide to the Constitution, Ordinary Americans: US History through the Eyes of Everyday People, and The Bill of Rights: A User’s Guide. For more than twenty years, she has written commentary for newspapers nationwide—including the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, and Chicago Tribune.