Select images from the American Civil War

Posted by Sandra Trenholm on Tuesday, 11/13/2012

In October 1862, Mathew Brady opened a photography exhibition at his studio in New York City. Entitled The Dead of Antietam, the exhibition attracted large crowds and brought the war home in a way that news articles and casualty listings could not. On October 20, 1862, an editorial in the New York Times explained that "the dead of the battle-field come up to us very rarely, even in dreams. We see the list in the morning paper at breakfast, but dismiss its recollection with the coffee. There is a confused mass of names, but they are all strangers; we forget the horrible significance that dwells amid the jumble of type. . . . Mr. BRADY has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it."

We are now in the midst of the 150th anniversary of the American Civil War. Mathew Brady’s Antietam images are but a small portion of the Civil War photographs that have captured and burned themselves into our collective American memory. What makes these photographs so compelling? Why after 150 years do we peer intensely at them to discern the tiniest details? For many, the images are moments captured in time—remarkable witnesses to history that reflect the humanity of the people and the destructive nature of the war. The words of the New York Times reviewer still ring true. The photographs allow a personal connection to history that the printed word cannot always deliver.

The staff of the Gilder Lehrman Institute has compiled a list of some of our most compelling Civil War photographs. With more than 4,000 images to choose from, it was difficult to narrow the list to those presented here. While we tried to be comprehensive in genre, we purposely did not choose any portraits.

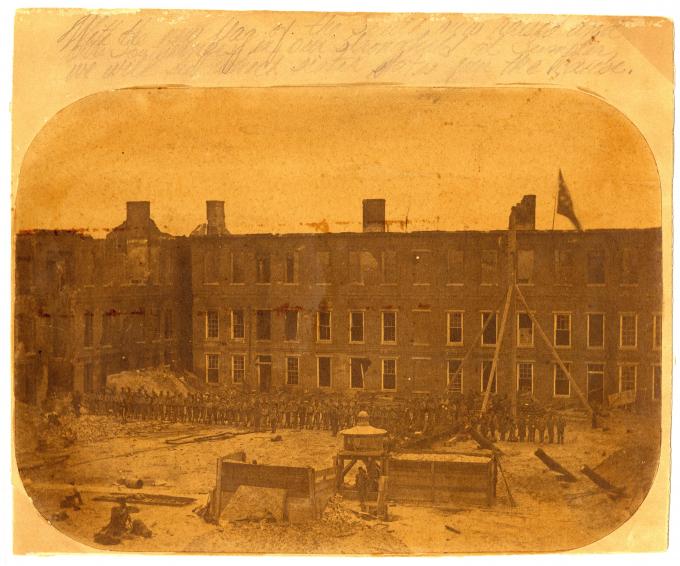

This image shows the first Confederate troops inside Fort Sumter in April 1861. It is a "salted paper print," the earliest type of photographic prints made on paper, where a salt solution embeds the image in the paper. According to a photograph conservator, the orange hue in this image was caused by a high iron content in the water, which has rusted. The pencil inscription at the top reads: "With the new flag of the south now raised and our Southerners in the stronghold at Fort Sumpter [sic], we will see which sister states join the cause." The back of the print contains a lengthier note to General Gideon Pillow: "The seriousness of the situation can best be shown, needless to say: leadership is important and Southern Sons are called to free our oppressions. Such a call as made to you without demand. Pillow - Tennesee, your life, your heritage in in [sic] the [illegible] of jeopardy! Rally and lead without hesitation in [illegible] means defeat. Defeat means death. Death means failure under the hands of scoundrels but [illegible] to who we allow to guide our destiny-. M.J. Davis, Char[leston]. S.C. April "

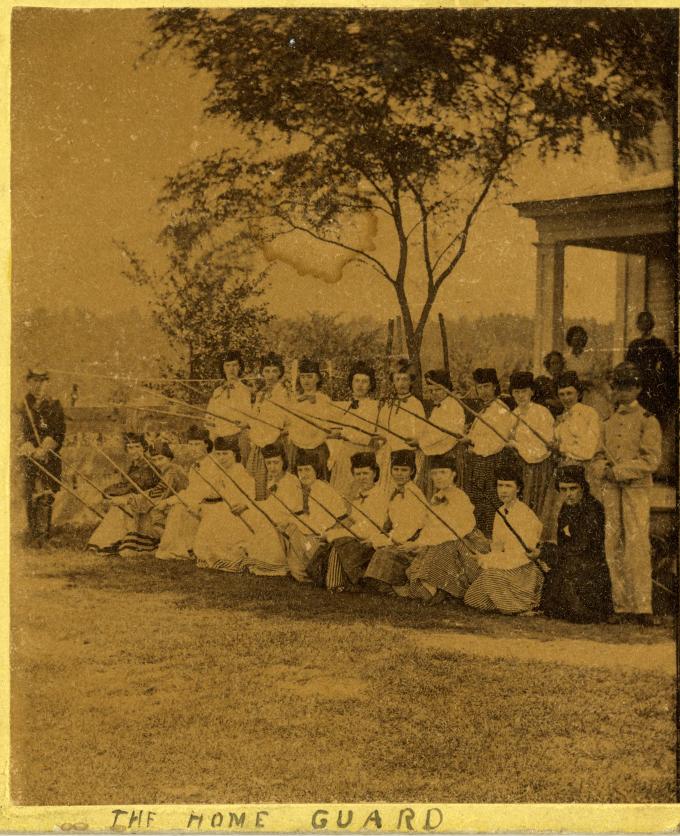

This is a close-up of a stereo card photograph entitled simply "The Home Guard." Research conducted by our curatorial staff turned up a copy at the Library of Congress with the caption "White Mountain Rangers" attributed to Andrew Gardner. Presumably taken at the outbreak of the war, the image shows a group of women dressed uniformly and armed with pikes or spears. Images such as this demonstrate public support of the war effort.

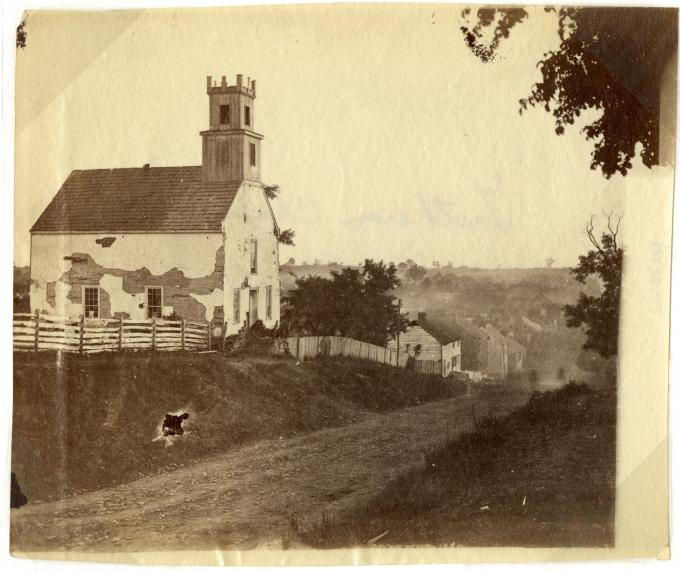

Built in 1768, this Lutheran church and cemetery stood east of Sharpsburg, Maryland. Its steeple was used by Confederate signal men during the Battle of Antietam as it came under fire from Union artillery. Even though it was used as a hospital immediately after the battle, the badly damaged building had to be torn down.

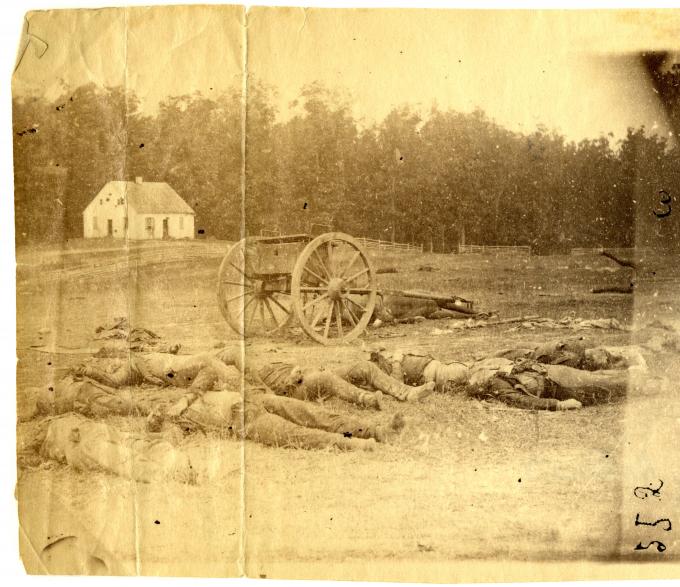

This is one of the most iconic and well-known images from the Battle of Antietam, September 17, 1862. During the battle the Dunker church was the focal point of a number of Union attacks against the Confederate left flank. After the battle, Confederates used the church as a temporary medical aid station. The juxtaposition of the dead soldiers in front of an Anabaptist church creates a powerful image.

These Confederate dead in the sunken road behind the wall at Marye’s Heights were killed during the Second Battle of Fredericksburg in May 1863. Captain Andrew J. Russell, the only non-civilian photographer in the Union Army, captured this photograph only hours after the battle had ended. Many photograhers staged such scenes by placing guns and bodies in positions that would result in more compelling photographs.

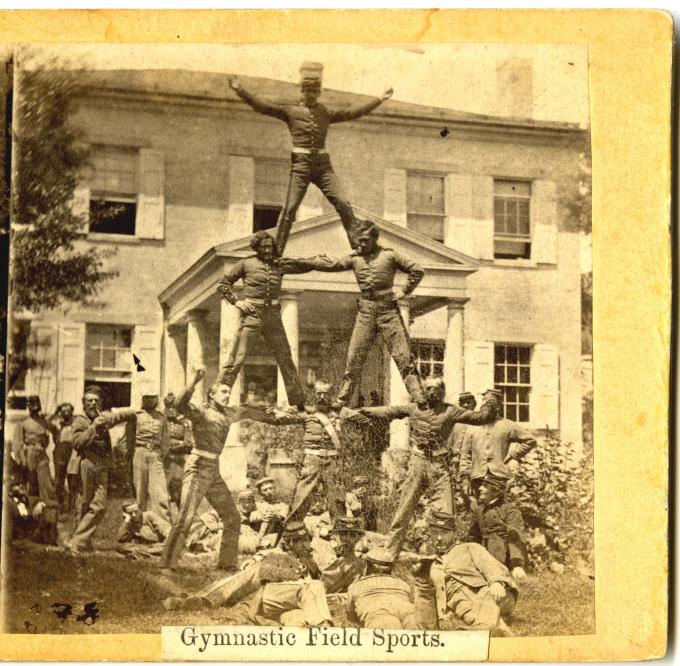

Even during a time of war, soldiers enjoyed leisure time. The uniforms suggest that this photograph may be of a New York regiment from 1861, before the switch to standard federal uniforms.

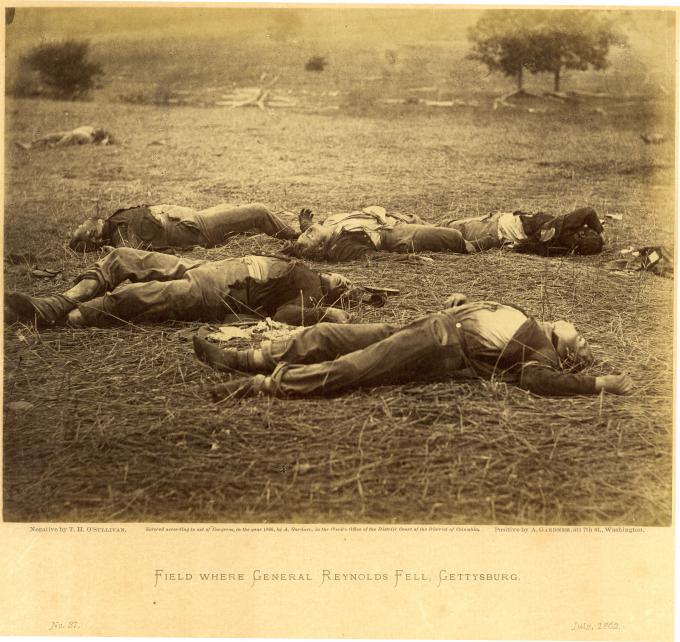

Photographers at Gettysburg moved the bodies around the battlefield to pose them in different locations and cited them as different units. These Union soldiers were killed on July 1, 1863. The diamond insignia visible on the right hand side of the photograph identifies them as part of the Union 3rd Corps. The insignia and several other visual clues in the photograph were used by historian William Frassinito to demonstrate that this is the same scene as Gardner’s "Harvest of Death," but taken from a different angle and misrepresented as being Confederate soldiers. William Frassanito, Gettysburg: A Journey in Time (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1975, 222–229)

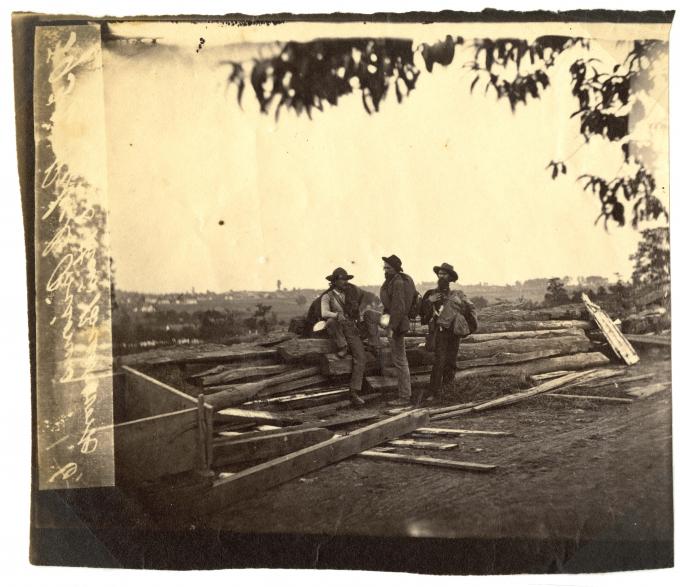

Dressed in classic Rebel uniforms, these Confederate prisoners posed for Mathew Brady near the Lutheran Theological Seminary on Seminary Ridge in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. This is one of the best-known photographic records of Confederate uniforms. Notations scratched in the glass plate negative are visible on the left hand side of the photograph.

Construction on the Tennessee state capitol at Nashville began in 1859. As photographer George Barnard explained in his book Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign, the "location selected was a commanding elevation in the center of the city, which places the base of the capitol somewhat higher than the roofs of the majority of the buildings near." During the siege of Nashville in 1862, it was reinforced by Union engineers and converted into the citadel of the fortifications above the city. It was the only state capitol that was fortified during the war.

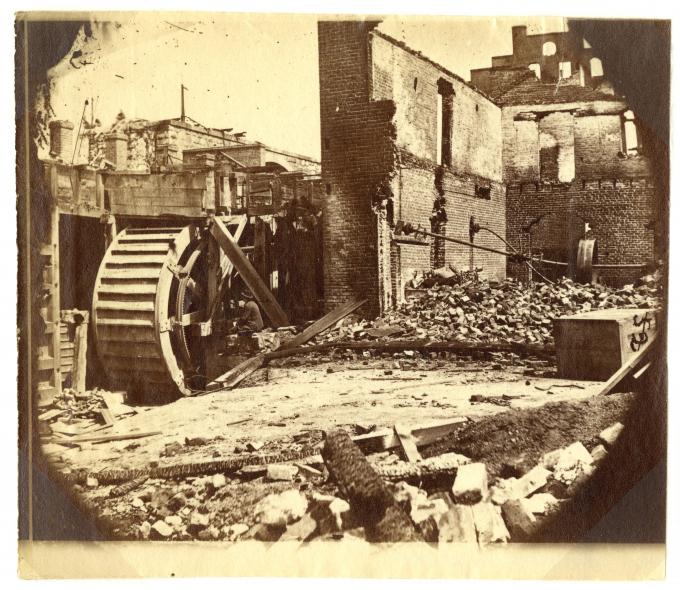

In April 1865, Confederate forces abandoned the city of Richmond, Virginia, setting fire to the Confederate capital as they retreated. Although Union troops attempted to put out the fires, roughly 25 percent of the city’s buildings were destroyed. This image shows the remains of a paper mill.

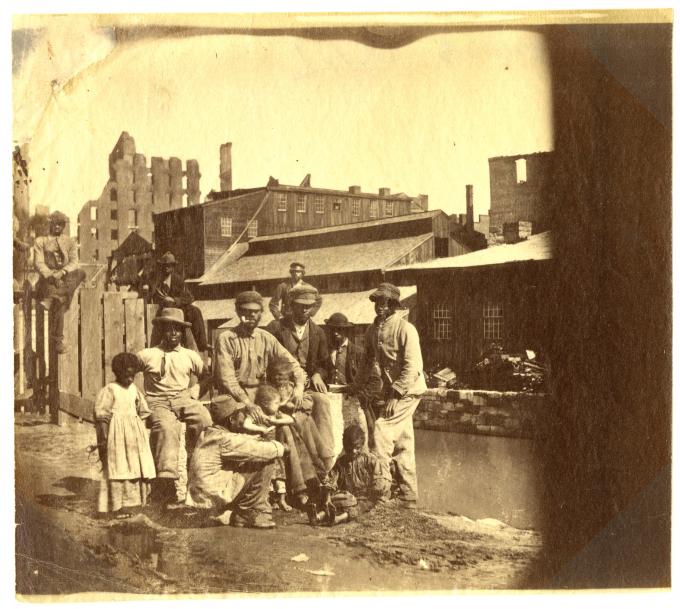

In this image freed slaves pose on the bank of the James River and Kanawha Canal in Richmond, Virginia. Slave labor was used to build the canal, which served as a vital commercial route for the city. The ruins of Haxall Flour Mills and the Gallego Mill can be seen in the distance.

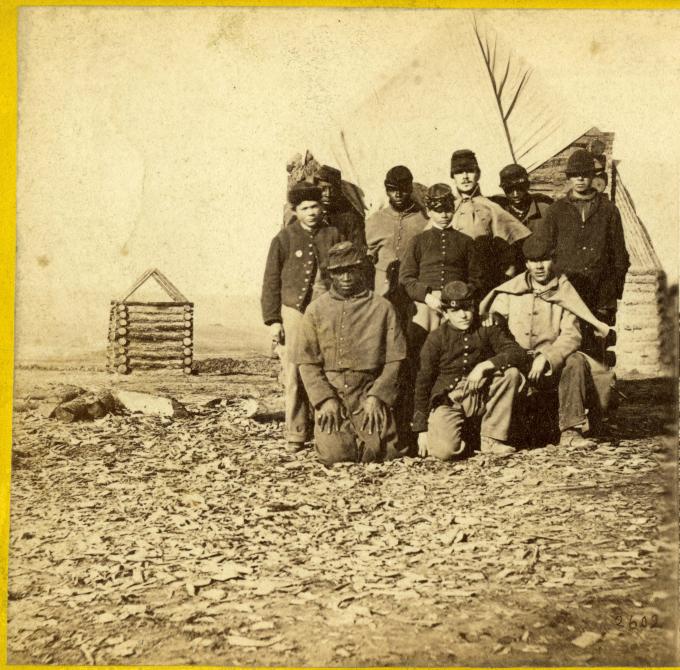

This stereocard was published as part of E & H.T. Anthony’s Photographic Incidents of the War. It doesn’t identify the "soldiers," most of whom look too young to shave.

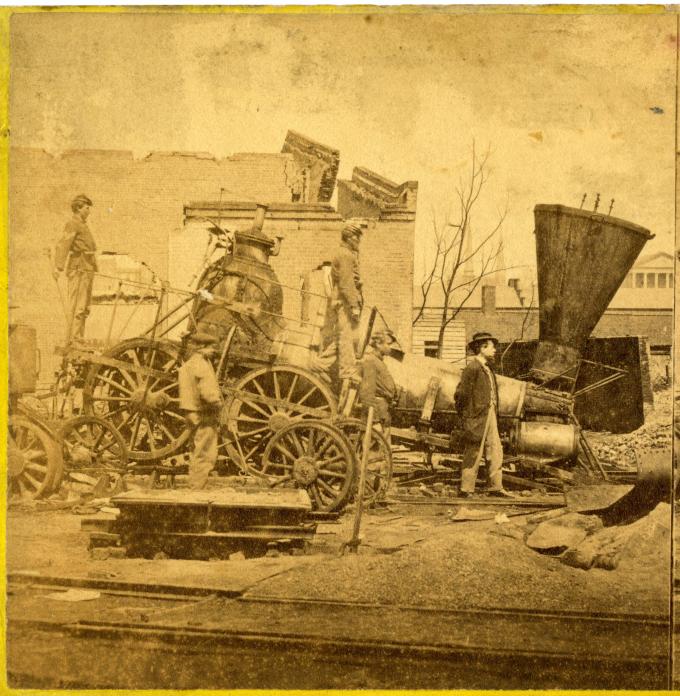

The locomotive shown above was most likely an American class 4-4-0 that was destroyed when the Richmond & Petersburg Rail Road depot burned in the fires that ravaged Richmond in April 1865.

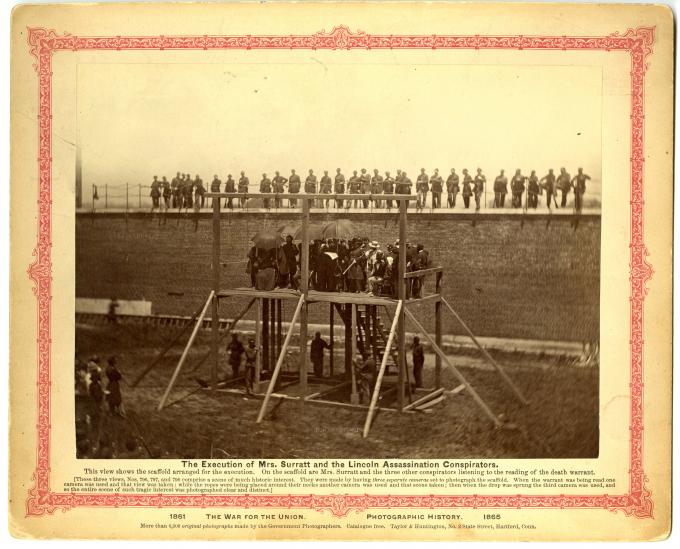

The execution of the Lincoln assassination conspirators captured the attention of mourning Americans across the country. The title and caption of this image places emphasis on Mrs. Surratt. There was significant debate as to whether she was truly involved in the assassination and many Americans simply did not want to see a woman executed.

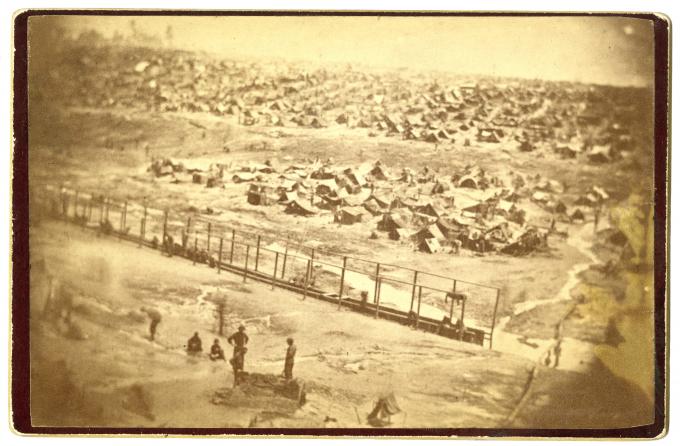

In February 1864, Confederates established Camp Sumter as a prison camp in Anderson, Georgia. The 26-acre, rectangular prison quickly became unbearable and prisoners suffered from an extreme lack of food, drinking water, and medical supplies, severe overcrowding, and poor sanitary conditions. Dubbed Andersonville by the prisoners, this camp had one of the highest death rates of the war. This rare photograph taken from the guard tower shows the latrines and tents used by the soldiers. Of the 45,000 men held at Andersonville, 30 percent, or 12,912 men, died while in captivity.

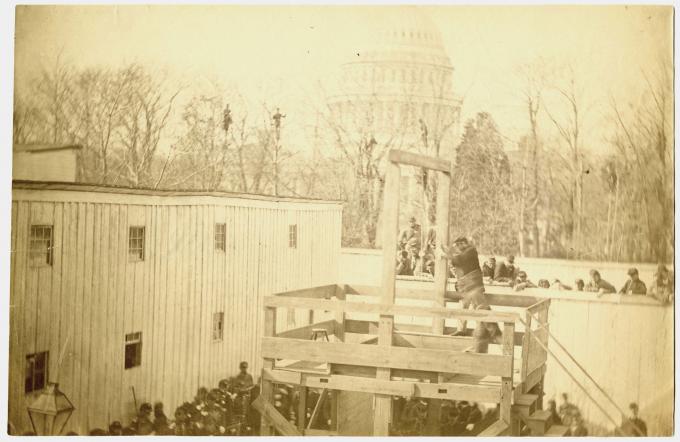

Although conditions in northern prison camps such as Elmira were also appalling, many northerners insisted that the abuse at Andersonville was deliberate and demanded vengeance. Captain Henry Wirz, commander of Andersonville, was tried by a US military court and found guilty of "impairing the health and destroying the lives of prisoners." He was executed in November 1865. This photograph shows the preparation of the gallows prior to his execution. The US Capitol looms in the background while spectators can be seen in the surrounding trees.

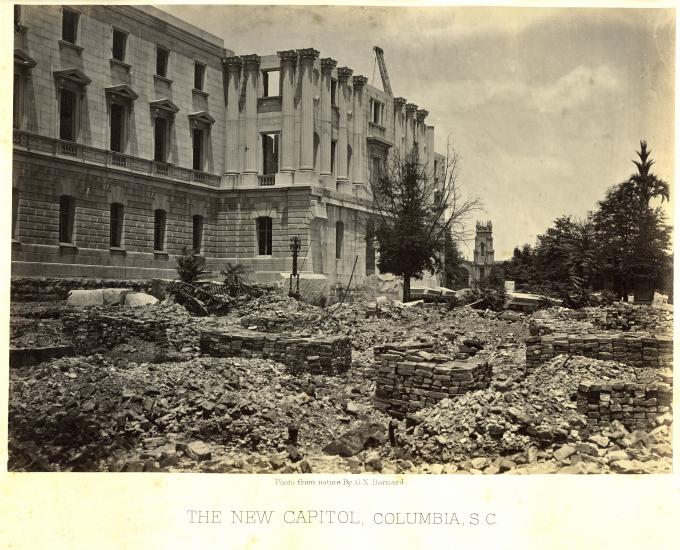

After Sherman’s troops completed their famous march through Georgia, they turned north to South Carolina and entered the capital in February 1865. No one knows if Union or Confederate troops started the fires that ravaged the city. Although Union troops and local fire companies tried to fight the fires, more than two-thirds of the city was destroyed. Sherman would order the destruction of the cities surviving public building before marching out of Columbia three days later.

This photograph shows the second inauguration of Abraham Lincoln, March 4, 1865, on the steps of the US Capitol. Although taken from a distance, the crowd on the steps and those gathered in front of the building are visible. The dome of the Capitol had been completed in December 1863, making Lincoln the first president to be inaugurated in the completed Capitol. Three men can be seen seated on top of the building near the base of the dome.