Abraham Lincoln, Mary Owens, and the accidental engagement

Posted by Sandra Trenholm on Wednesday, 04/18/2012

In 1836, Abraham Lincoln found himself in a tenuous situation. He was engaged to a woman he barely knew and didn’t want to marry. Mrs. Elizabeth Abell had been pushing for a romance between Lincoln and her sister, Mary Owens, whom Lincoln had met briefly in 1833. When Elizabeth went home to visit her family in Kentucky three years later, she said she would bring Mary back to Illinois if Lincoln would agree to marry her. Lincoln jokingly agreed. He realized the consequences of his rash statement when Mary came to New Salem and considered herself engaged. Lincoln immediately regretted his promise, and his papers record his objections to the woman’s appearance, weight, and temperament.

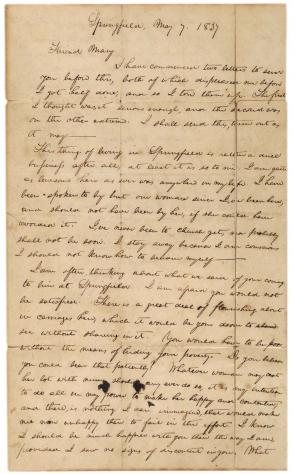

Too honorable to simply break the engagement, Lincoln wrote three letters to Mary during their engagement, painting a bleak image of their future and subtly suggesting that she could do better. This letter, the second in the series, is dated May 7, 1837, just after Lincoln moved from New Salem to Springfield. Mary would end their engagment in the fall.

Friend Mary

I have commenced two letters to send you before this, both of which displeased me before I got half done, and so I tore them up. The first I thought wasn’t serious enough, and the second was on the other extreme. I shall send this, turn out as it may.

This thing of living in Springfield is rather a dull business after all, at least it is so to me. I am quite as lonesome here as ever was anywhere in my life. I have been spoken to by but one woman since I have been here, and should not have been by her, if she could have avoided it. I’ve never been to church yet, nor probably shall not be soon. I stay away because I am concious I should not know how to behave myself-

I am often thinking about what we said of your coming to live at Springfield. I am afraid you would not be satisfied. There is a great deal of flourishing about in carriages here; which it would be your doom to see without sharing in it. You would have to be poor without the means of hiding your poverty. Do you believe you could bear that patiently? Whatever woman may cast her lot with mine should any ever do so, it is my intention to do all in my power to make her happy and contented; and there is nothing I can immagine, that would make me more unhappy than to fail in the effort. I know I should be much happier with you than the way I am, provided I saw no signs of discontent in you. What you have said to me may have been in jest, or I may have misunderstood it. If so, then let it be forgotten; if otherwise, I much wish you would think seriously before you decide. For my part I have already decided. What I have said I will most positively abide by, provided you wish it. My opinion is that you had better not do it. You have not been accustomed to hardship, and it may be more severe than you now immagine.

I know you are capable of thinking correctly on any subject, and if you deliberate maturely upon this, before you decide, then I am willing to abide your decision.

You must write me a good long letter after you get this. You have nothing else to do, and though it might not seem interesting to you, after you have written it, it would be a good deal of company to me in this "busy wilderness". Tell your sister I dont want to hear any more about selling out and moving. That gives me the hypo whenever I think of it.

Yours &c.

Lincoln