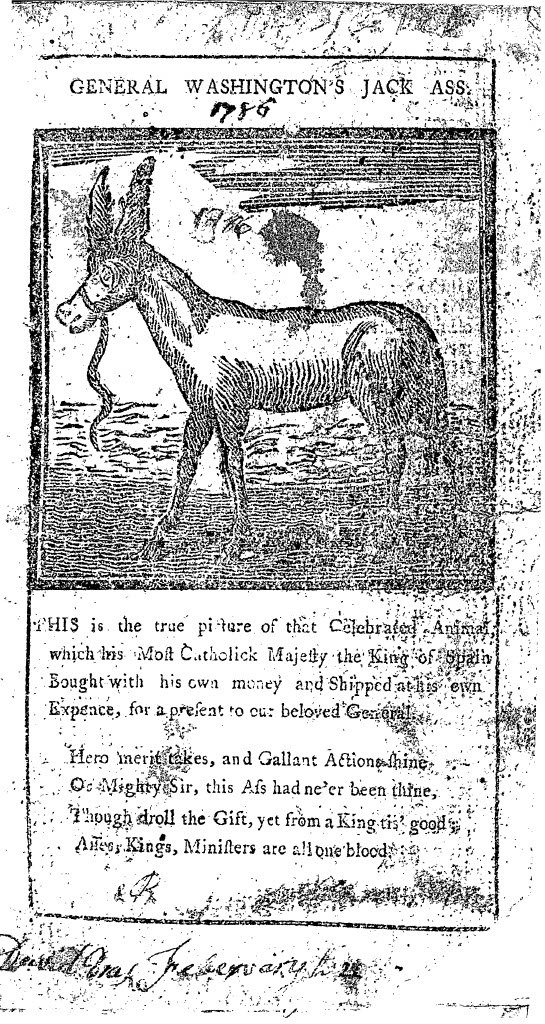

Spain's "Royal Gift" to George Washington, 1784

George Washington, as a landowner, was an agricultural scientist anxious to improve production on his plantations. His political experiences brought him into contact with agriculturalists from around the world and his military experiences included the challenge of moving troops and equipment long distances. All of this explains why the cosmopolitan gentleman who was America’s first president also knew a lot about donkeys.

Bringing donkeys to the newly founded United States would have been considered innovative. Eighteenth-century American farmers relied on horses and oxen to plow fields and haul heavy loads. The reason for this was historical: Donkeys were not common or necessary in England, where the terrain was relatively level, and most colonial-era farmers were English. However, Washington understood that donkeys would be perfect for working the hilly lands in the US. He planned on importing male donkeys (known as jacks) to breed with his best mare and produce high-quality mules (which are a cross between donkeys and horses). But where could he obtain the male donkeys?

Bringing donkeys to the newly founded United States would have been considered innovative. Eighteenth-century American farmers relied on horses and oxen to plow fields and haul heavy loads. The reason for this was historical: Donkeys were not common or necessary in England, where the terrain was relatively level, and most colonial-era farmers were English. However, Washington understood that donkeys would be perfect for working the hilly lands in the US. He planned on importing male donkeys (known as jacks) to breed with his best mare and produce high-quality mules (which are a cross between donkeys and horses). But where could he obtain the male donkeys?

The best donkeys in the world came from Spain. Spain recognized the superiority of its animals and made it illegal to export them out of the country; donkeys were a protected national resource. Washington would therefore need permission from the Spanish king, Carlos III, to get Spanish donkeys for Mount Vernon.

Washington made his first attempt to acquire a donkey during the Revolutionary War. Unfortunately, Juan de Miralles, the Spanish agent with whom he worked, died in April 1780 before Washington could obtain the animal. After the war, Washington returned to Mount Vernon and renewed his efforts to bring Spanish donkeys to the US. In July 1784, he wrote to Robert T. Hooe for assistance:

I am convinced that a good Jack would be a public benefit to this part of the Country, as well as private convenience to myself. . . . An ordinary Jack I do not desire; I will describe therefore such an one as I must have, if I get any. He must be at least fifteen hands high; well formed; in his prime; and one whose abilities for getting Colts can be ensured.

This was something more than a personal request from Washington. It quickly evolved to include government officials from the US and Spain. Hooe asked Richard Harrison, the consul for the United States in Cadiz, and William Carmichael, the US chargé d’affaires at the Spanish court, for assistance. Carmichael contacted the Spanish foreign minister, José Moñino y Redondo, Conde de Floridablanca, who obtained King Carlos’s permission in November 1784.

Carmichael reported the good news back to Washington, but worried about Washington accepting a favor from the Spanish king. “I must confess sincerely that I shall be uneasy until I have your Approbation. The glory that you have acquired needs not the attention of a Monarch to augment it. But you are now a Citizen of the United States and as such will interest yourself in the Smallest circumstance that can contribute to its prosperity.” Washington could be grateful but must give no impression of being bribable.

Thomas Cushing, the lieutenant governor of Massachusetts, informed Washington that the jacks arrived in Boston on October 7, 1785. King Carlos III’s foresight in sending two animals proved accurate. One of the donkeys died during the voyage. Washington sent his overseer, John Fairfax, to escort the aptly named Royal Gift and his Spanish caretaker back to Mount Vernon.

Washington began breeding Royal Gift with horses on his own plantation and horses throughout the South. Royal Gift became the progenitor of the modern American Mammoth Jackstock. In 1785, there were 199 horses at Mount Vernon. By 1799, there were twenty-seven horses, twenty mules, and sixty-three donkeys. Washington’s experiment established the donkey’s viability and utility. According to the American Mule Museum, “by 1808, the U.S. had an estimated 855,000 mules worth an estimated $66 million.”

The documents featured here highlight Washington’s passion for improving Mount Vernon and revolutionizing farming. They also substantiate Washington’s international reputation and illuminate Spain’s respect for and friendship with the United States.

Excerpt

William Carmichael to George Washington, December 3, 1784

The King has not only condescended with pleasure to permit the extraction of the Jack Ass which you sollicit on acct of General Washington But further his Majesty desirous that this Commission should be executed to the entire Satisfaction of so distinguished a personage, has ordered me to look out for & place at your orders two of the best of those Animals, in case that an accident should happen to one on the passage. I shall advise you when they are ready. . . .

A full transcript is available.