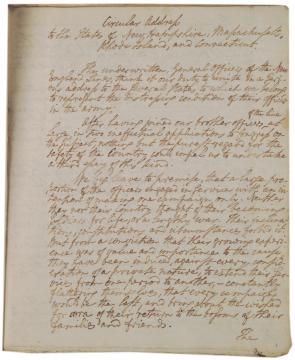

George Washington and the Newburgh Conspiracy, 1783

A Spotlight on a Primary Source by George Washington

In March of 1783, George Washington faced a serious threat to his authority and to the civil government of the new nation. The Continental Army, based in Newburgh, New York, was awaiting word of peace negotiations between Great Britain and the United States. The men were restless, anxious to go home, and increasingly angry about delays in pay and lack of provisions. A petition to Congress from the officers for pay for the men and assurances of pensions for the officers had been met in January with more promises but no concrete action.

In March of 1783, George Washington faced a serious threat to his authority and to the civil government of the new nation. The Continental Army, based in Newburgh, New York, was awaiting word of peace negotiations between Great Britain and the United States. The men were restless, anxious to go home, and increasingly angry about delays in pay and lack of provisions. A petition to Congress from the officers for pay for the men and assurances of pensions for the officers had been met in January with more promises but no concrete action.

The situation came to a head with a call on March 10 for a meeting of officers the next day. It was accompanied by the so-called First Newburgh Address by "a fellow soldier." The document accuses America of trampling on the soldiers’ rights and suggests that, if peace was declared, the Army could refuse to lay down their arms until their demands were met; alternatively, if the war continued, the Army could simply retire from the field and leave America to the British.

Washington, appalled at the threat of using the Army against civil authority, condemned the "irregular invitation" but recognized that his own authority would be undermined if he turned his back on the concerns of the men and officers. He therefore issued his own orders on March 11 for a meeting on March 15. Meanwhile, a second missive from the anonymous soldier, the Second Newburgh Address, claimed that Washington’s words and actions showed his support for the Army’s demands, further angering Washington. As he prepared for the March 15 meeting with his officers, he urged Congress to seriously consider providing some relief to the soldiers.

On March 15, Washington stood before his officers in Newburgh and eloquently and emotionally expressed his disapprobation of the actions proposed in the anonymous soldier’s addresses: "This dreadful alternative, of either deserting our Country in the extremest hour of her distress, or turning our arms against it . . . has something so shocking in it, that humanity revolts at the idea. – My God! what can this writer have in view by recommending such measures? can he be a friend to the army – can he be a friend to this Country? Rather is he not an insidious foe?" As Washington prepared to read to them an account of Congress’s desperate financial straits, he pulled out his new spectacles, and concluded with the now historic appeal: "Gentlemen, you must pardon me. I have grown gray in your service and now find myself growing blind."

Whether it was this last appeal, or shame brought on by Washington’s disappointment in an army that could threaten such disloyalty, the officers voted to reject the Newburgh Addresses and asked Washington to negotiate with Congress to redress the wrongs they had brought to the government’s attention in their January petition. The Newburgh Conspiracy was one of the greatest tests of the commander in chief’s leadership, and was resolved peacefully and respectfully. The Army’s concerns were never completely addressed, but Washington’s urgent request that they work with rather than against the government and Congress’s actions to redress some of the problems, carried the military, and the nation, through the end of the war.

Documents related to the Newburgh Conspiracy were collected by the Army and, according to Washington’s General Orders of March 18, "being too prolix to be inserted into the Records of the Army, will be lodged at the orderly office, to be perused or copied by any Gentleman of the Army who may think proper."