"Citizen 13660" by Miné Okubo, an illustrated memoir of Japanese incarceration during World War II, 1946

A Spotlight on a Primary Source by Miné Okubo

Click the images to enlarge them.

Click the images to enlarge them.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, resulting in the incarceration of all people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. The order was issued in response to Japan’s attack on the Pearl Harbor Naval Base on December 7, 1941. The surprise attack had spurred anti-Japanese racism. With the establishment of the War Relocation Authority to carry out Executive Order 9066, all Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans were treated as potential enemy operatives.

Over the course of the war, the US Army forcibly moved approximately 120,000 people to temporary assembly centers before bringing them to detention camps. Not knowing if they would ever be free to return, and given as little as 48 hours notice, many people of Japanese ancestry sold their homes and businesses at great financial loss, assigned the use of their property to neighbors, or abandoned their property. Once located in camps, Japanese American citizens and noncitizens alike were closely supervised. They were required to prove their allegiance to the United States through investigations and loyalty questionnaires.

Over the course of the war, the US Army forcibly moved approximately 120,000 people to temporary assembly centers before bringing them to detention camps. Not knowing if they would ever be free to return, and given as little as 48 hours notice, many people of Japanese ancestry sold their homes and businesses at great financial loss, assigned the use of their property to neighbors, or abandoned their property. Once located in camps, Japanese American citizens and noncitizens alike were closely supervised. They were required to prove their allegiance to the United States through investigations and loyalty questionnaires.

Miné Okubo was born in Riverside, California, in 1912. She was an art student at the University of California when she was forcibly brought to the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, CA, then transferred to the Topaz War Relocation Center in Millard County, Utah. Okubo was motivated to document camp life through sketches, as detainees initially were not permitted to bring cameras into the camps. Okubo compiled her drawings into an illustrated memoir, Citizen 13660 (1946), named for the number assigned to her family by the Wartime Civil Control Administration. Citizen 13660 chronicles Okubo’s forced removal from home and day-to-day life in Tanforan and Topaz. Her account conveys the discomforts, tedium, and horrors of camp life, as well as the resourcefulness of people in the camps who found ways to remake their environment to retain dignity and find fulfillment.

Miné Okubo was born in Riverside, California, in 1912. She was an art student at the University of California when she was forcibly brought to the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, CA, then transferred to the Topaz War Relocation Center in Millard County, Utah. Okubo was motivated to document camp life through sketches, as detainees initially were not permitted to bring cameras into the camps. Okubo compiled her drawings into an illustrated memoir, Citizen 13660 (1946), named for the number assigned to her family by the Wartime Civil Control Administration. Citizen 13660 chronicles Okubo’s forced removal from home and day-to-day life in Tanforan and Topaz. Her account conveys the discomforts, tedium, and horrors of camp life, as well as the resourcefulness of people in the camps who found ways to remake their environment to retain dignity and find fulfillment.

Excerpts

From Miné Okubo, Citizen 13660 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1946)

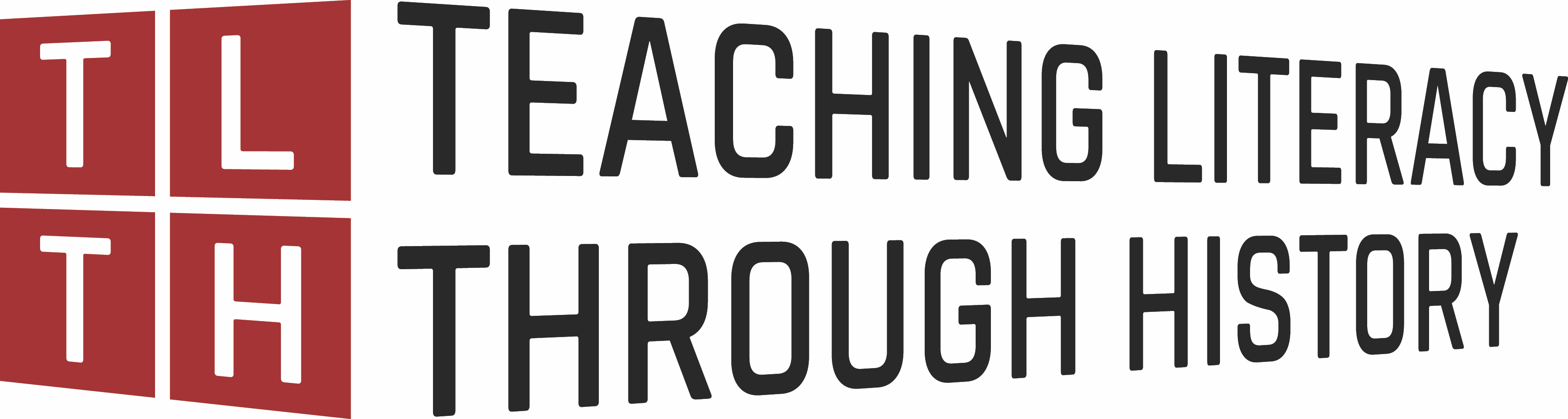

On April 24, 1942, Civilian Exclusion Order No. 19 was issued and posted everywhere in Berkeley. Our turn had come. We had not believed at first that evacuation would affect the Nisei, American citizens of Japanese ancestry, but thought perhaps the Issei, Japanese-born mothers and fathers who were denied naturalization by American law, would be interned in case of war between Japan and the United States. It was a real blow when everyone, regardless of citizenship, was ordered to evacuate. (p. 17)

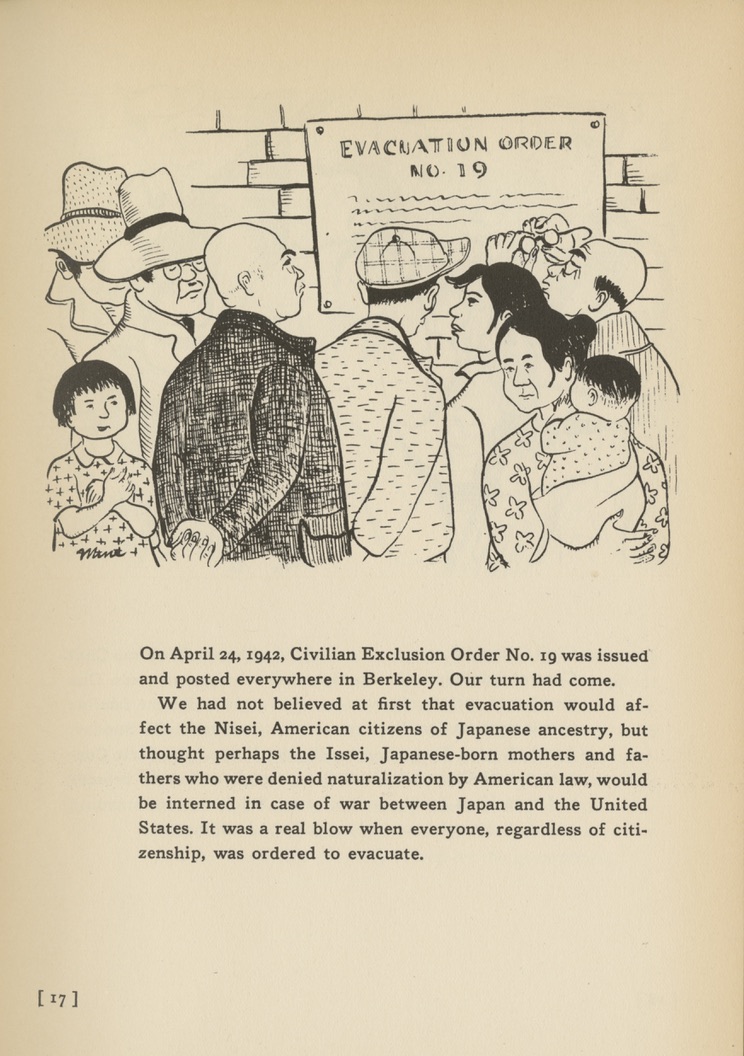

We were close to freedom and yet far from it. The San Bruno streetcar line bordered the camp on the east and the main state highway on the south. Streams of cars passed by all day. Guard towers and barbed wire surrounded the entire center. Guards were on duty day and night. (p. 81)

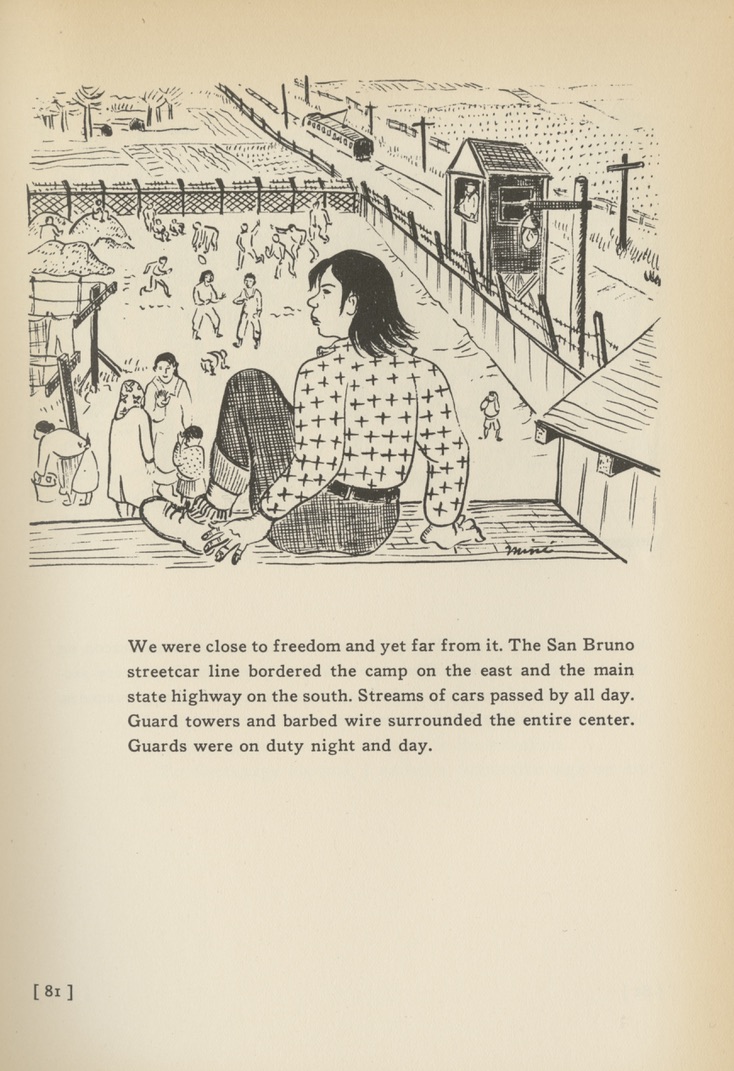

In Tanforan Assembly Center a movement for self-government was started by the evacuees. They organized a campaign complete with slogans and rallies to elect an official Center Advisory Council. The election gave the Issei their first chance to vote along with their citizen offspring. But army orders later limited self-government offices and votes to American citizens. To our disappointment, in August an army order dissolved all Assembly Center self-government bodies. (p. 91)